In 1726, in one of the most important events in economic history, a three-year-old Scottish boy was stolen by gypsies.

Whether or not the boy, as his biographer later noted, "would have made, I fear, a poor gypsy," our praise is due to the quick-acting uncle that returned young Adam Smith to his family.

Smith's shadow over American politics is a long one. The author of the seminal On the Wealth of Nations, today the great economist serves largely as an adopted hero of the political right -- founding genius of modern capitalism, optimistic icon of laissez-faire, unwavering apostle of the market's "invisible hand."

The old Scot is certainly no stranger to the campaign trail. Speaking at the University of Chicago in March, Mitt Romney proclaimed that "when the heavy hand of government replaces the invisible hand of the market, economic freedom is the inevitable victim." Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz countered that "the reason that the invisible hand often seems invisible is that it is often not there." It took mere days for the debate over the "you didn't build that" to revive an argument over whether Adam Smith would have supported Democratic government activism or Republican laissez-faire.

Why does Smith's famous tagline, despite appearing only once in his 700-page opus, still feel so central to us two centuries later?

Because nearly all of the economic debate between progressives and conservatives in 2012 -- reenacted ad nauseam in convention speeches, around water coolers, and on cable TV -- boils down to this question: is the free market, left to itself, the greatest guarantor of human happiness? Does "the invisible hand" really work?

Let's find out what Adam Smith thought.

---

First, a few words to bring the man himself into focus. Smith was, by all accounts, an odd duck. Blessed with an ample nose, bulging eyes, and a prominent lower lip -- "I am a beau in nothing but my books," he once quipped -- Smith was a lifelong bachelor who spent most of his adulthood living with his mother. He was also almost comically absent-minded. Known for murmuring constantly to himself since boyhood, he once wandered 15 miles in his nightshirt, puzzling over a late-night query, until the churchbells of the next village brought him back to earth.

Adam Smith, odd duck.

This absent-minded professor par excellence was also wildly popular with his students, and in his extensive European travels was flattered and fêted by such non-slouches as Benjamin Franklin and Voltaire. The mid-1700's was also, Bonnie Prince Charlie excepted, a fantastic time to be a Scot. By Smith's heyday, Edinburgh was known as "the Athens of Britain;" in contrast with Oxford and Cambridge, its university lay in the physical heart of a dense urban culture which hummed and brimmed with new ideas. Edinburgh's intellectuals -- led by the eloquent and searingly anti-religious David Hume -- threw themselves at the widest range of disciplines, using clear-eyed Scottish practicality to clear the cobwebs of European abstraction and superstition.

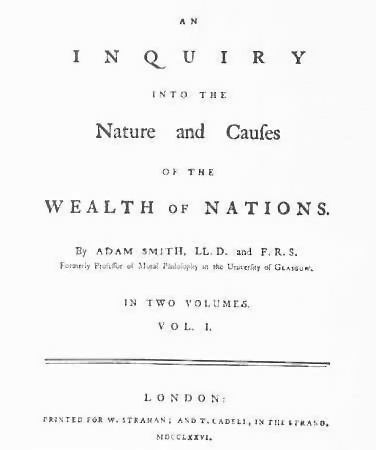

Out of this rich Enlightenment brew came Smith's two great works, A Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and The Wealth of Nations (1776). These works are built on a premise Smith inherits from Hume: that as inherently social creatures, human beings deeply depend on one another. The Theory of Moral Sentiments and Wealth of Nations take man as a social animal and ask, respectively, 'What makes us happy?', and 'What makes us rich?'.

To those of us not surnamed Kardashian, these questions may seem at cross-purposes. To Smith, however, understanding the mechanisms of the marketplace and the mechanisms of the human heart formed a single and essential mission.

His answers to both questions boil down to a single word: sympathy.

In A Theory of Moral Sentiments, the Scotsman argues that each one of us naturally seeks out a "mutual sympathy of sentiments" with the people around us, sharing our joys and frustrations with our friends and taking on theirs as our own.

This seemingly simple impulse, Smith writes, is made possible by a series of intricate, imaginative leaps beyond ourselves -- both to let us feel what others might feel, but also to judge our own situation based on how a spectator would see us. We make these leaps a thousand times a day, on matters great and small, and how well we perform them determines our success as a member of society. Two hundred years before our notion of "soft skills," Adam Smith had the idea worked out in full.

Our gift for sympathetic imagination ends up paying huge dividends: when our emotions run hot, sympathy helps them cool; when we don't know what to do, sympathy helps us figure out right from wrong. And (foreshadowing alert!) from thousands and millions of individual acts of sympathetic imagination arise, without any prescription from above, in near-invisible fashion, the shared habits and communal rules that allow human societies to flourish.

Read 'A Theory of Moral Sentiments' - On how sympathy helps both sides live better:

But if humans create this kind of spontaneous social order from below, what do we need government for? The Wealth of Nations is Smith's answer.

1776: A good year for new ideas.

With his magnum opus, Smith set himself two main goals: first, create the most comprehensive account ever written on political economy; second, stop politicians from acting like idiots. On this, he went a strong one for two.

As friend and advisor to many senior British officials, Smith was convinced that the protectionism then in vogue in European capitals -- taxing or blocking foreign imports to boost domestic industries -- was a disastrous mistake. He had strong opinions about taxation and education reform as well, as we shall see, but defending free trade was Smith's real idée fixe.

Just as in the Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith chooses to begin his grand project not with abstract principles or grand figures, but with common-sense facts of social life.

Read 'The Wealth of Nations' - On the beginnings of capitalism:

Notice the resonances between Smith's genesis of capitalism and his genesis of human morality. Smith is no wide-eyed optimist about human nature. The sympathy that drives markets and creates manners is not an altruistic sympathy: it's a social one.

Capitalism begins here.

And neither markets nor morals work without that basic imaginative exchange: What does he want? What do I want? How do we meet in the middle?

And so, on to the most famous buzz-phrase in economic history. What follows is the sole appearance of the "invisible hand" in Smith's work. The phrase is delivered as part of one of Smith's many salvos against protectionism. Specifically, it arrives just after an explanation of why English merchants will prefer to invest more of their capital in England -- they enjoy being able to check up on it personally; they know English courts are more likely to uphold their rights -- without needing any further encouragement from government.

Read 'The Wealth of Nations' - On the invisible hand:

As the passage makes clear, Smith trusts the spontaneous order of individual human choice over the fanciful designs of the state. But over the course of Books IV and V, Smith makes it equally clear that the "invisible hand" is not a cure-all. Markets tend toward monopoly, and would-be monopolists are not to be trusted any more than utopian politicians. As such, a wise government will step in to invest where the market won't, and stop the excesses to which all markets are prone.

Read 'The Wealth of Nations' - On why government should invest in infrastructure:

Read 'The Wealth of Nations' - On why government should invest in education:

Adam Smith's passages on taxation are the ones least likely to be quoted on Fox News. Yes, the hero of the invisible hand did in fact say, "Every tax is to the person who pays it a badge, not of slavery, but of liberty." But Smith's ideal government is a strictly limited one, and as seen in the above two passages, he was determined that every government project should, to the greatest possible extent, pay its own way.

Smith clearly prefers individual choice to central planning. At the same time, he returns time and again to the idea that fairness and interdependence are what enable all human endeavors. Where government can best safeguard that fairness and interdependence, Smith observes, it has a responsibility to do so.

As fertile a mind as he had for ideas, Adam Smith was no idealist. He knew that the real world adheres to no system, and that, at least in politics, no good idea goes unpunished. Our final passage shows Smith to be especially well-attuned to the "special interests" of his own day.

So would Adam Smith support the Romney vision of government, or the Obama vision?

On the President's side, the Wealth of Nations is decidedly not the Quran of market fundamentalism some of its defenders would have us believe, nor would its author be likely to side with the 1% on most issues. Romney could, for his part, justifiably invoke Smith's warnings about government excess, and his unwavering faith in individual choice over state prescription. The Scot may well have welcomed a plague on both their houses.

Nevertheless, it is worth remembering in our age of economic turmoil that Adam Smith's free market is in tune with, and an extension of, that most basic human conversation: we need each other's help; I can give you this if you can give me that. A Smithian economy thrives not on selfishness, but on decency; its watchword is harmony, not greed.

At our core, Smith teaches us, we behave decently not because the police or the FEC tell us to, but because we naturally want to -- because we enjoy the dialogue and do far better for ourselves when it works. Whether our real motivation is kindness or self-interested practicality, in the end, hardly matters.

We're human. We can imagine it from both sides.