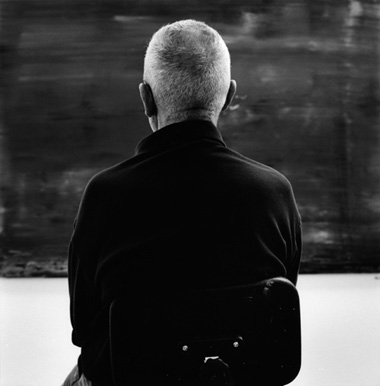

Anton Corbijn, Gerard Richter, b/w photography, 146 x 146 cm, Courtesy of the Artist

Dutch photographer and film director Anton Corbijn once declared his interest in portraying the pain of creation. Devoted to some of the most renowned living artists, his recent black-and-white series features painters, musicians, and a moving portrait of Nelson Mandela. Combining austerity and aesthetic qualities, these black and white prints strike us for the way they capture the geniality of the portrayed. In a quiet but striking way, these apparently spontaneous but perfect shots speak to us about the act of creation. These photographs reveal Corbijn's affectionate and attentive look, his sense of amazement and his identification with others.

Despite stylization, Corbijn's photographs display a strange closeness and a sense of intimacy. Seemingly naked, the strength of these photographs comes from the accidental as well as the intentional, which coexist in the process of their making. Strongly indebted to Minimalism (as evident in the photograph of Gerard Richter), Corbin's vocabulary is bare, almost verging into silence. Bringing up a sense of wonder for the creative process of others, and a look into its shattering dilemmas, Corbijn's new series of photographs confirms this photographer's faith and pleasure as an artist himself.

I had a chance to sit down with Anton Corbijn for a frank conversation about his work and process.

LR -- You have been working as a photographer since 1972. What are your thoughts when you look back at some of your photographs that have become iconic?

AC -- My first pictures are from 1972, and my first proper camera dates back to 1973. During the first year I used my father's camera. It had a flash on it, which I don't like, but I didn't know anything about photography back then, so it was just what I did. Then I worked during my school's holidays at a factory and was able to buy my own camera with my own money. It was weird, I think I was lucky that in the seventies I lived in a small place in Holland so no one noticed all my mistakes. I published sometimes and I probably made a lot of mistakes, but I was able to learn while photographing. In the mid 70s until the late 70s, I started to make some pictures that I felt okay with. They corresponded to what I had in mind though I still felt that I couldn't quite get it. The Memphis Slim photo was around 1973. This is one of my favorite pictures from that early period. And from 1976 onwards while in Holland I got Steely Dan, Ry Cooder, Jack Bruce, Costello and John Martyn. I started to get some pictures that portrayed what I had in mind, but people didn't like them. There was no great reaction to the work. Although I really didn't know anything about photography, I felt with these pictures -- when I printed them -- that there was something special about them. I sensed that these were pictures that could last longer than people realized at the time. I really felt that they would last and move beyond the popularity of the person in them. They were separate from the subject's fame, they became something else and I think that was what I was looking for. I slowly started to get images now and then that functioned in this way. In 1979 I moved to England and photographed Joy Division and Bowie and Beefheart. At that time I got images that I felt had that special, well -- power is a big word to say -- more like intimacy and ambition that outlasted the photo shoot. I felt that they would have a longer life.

LR -- Some of these photographs have became a part of History and the way we remember things, such as the Joy Division photograph. Do you feel a responsibility for the way things will be remembered?

AC -- I feel a responsibility to myself, and not so much for the world at large. Because of my Calvinistic upbringing, I was trained to think that what you do has to have a purpose. Taking pictures that only satisfy an editorial would mean that they have no value beyond that. I felt that I would be letting myself down if I did that, because I always thought I was making something that had a reason to exist. Otherwise it would be a waste of energy.

Anton Corbijn, Anselm Kiefer, b/w photography, 146 x 146 cm, Courtesy of the Artist

LR - You are often misunderstood and quickly labeled as a "rock-photographer." Do you feel that the celebrity status of the people you have photographed over the years has stood in the way of your being accepted by the art world? For example, Avedon's portraits helped define our age of celebrity and are a part of it as well. But Avedon also looked into subjects who are not famous. In the early '80s he traveled through the American West and took pictures of young people, workers, and drifters.

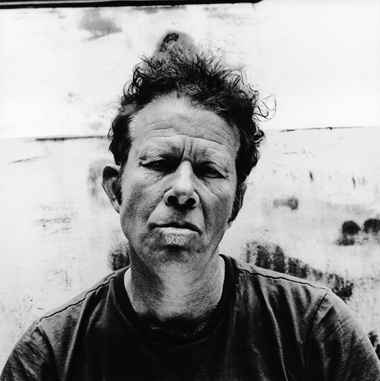

Anton Corbijn, Tom Waits, b/w photography, 146 x 146 cm, Courtesy of the Artist

AC -- That is more the perception of the media than the art world - although in England it is different. In a lot of countries my work has gone beyond that. And even in your question I detect that you think that I am photographing celebrities, but I don't think I do. I photograph artists, and some of them are very well known but if you ask the average man on the street: Do you like Anselm Kiefer? He would stare at you with a blank stare, because these are not celebrities. They are celebrated in a specific circle. But I am not really shooting a lot of Madonna or Paris Hilton or any of these big celebrities. People like Bono are big celebrities now but were not when I started working with them, celebrity status was not why I photographed him. So I hope that people look beyond this issue, and look at the fact that I photograph people I find interesting. And that is why I moved towards painters, because I find them incredibly interesting. And whether I sell these pictures, or people publish them, is something else. I just wanted to make photographs of people I wanted to meet, and wanted to do something in photography with them. When you mention Avedon who did the American West...funny, I find the Tom Waits picture slightly reminiscent of some of his pictures. Don't you think so?

LR -- Yes I do. Since there is a certain earnestness and intensity...

AC -- Yeah, he looks like a drifter, also the background. It is one of my favorite series by Avedon, because I am not such a big fan of fashion and that seemed to be a very different way of photographing people.

LR -- Wonder and closeness seem to be important aspects in your photography as well as in your films. I am thinking about your emotional relationship to Joy Division and Ian Curtis in Control, the close-ups and the intensive way you film George Clooney in The American, and the fact that almost all your photography is frontal. I wonder about your recent journey into film. Is this how you stay curious about the creative process? Is it a way of re-inventing yourself as an artist?

AC -- These are two different types of curiosity, because my photography is much about people and film is more about stories. So they are different things. Yes, this may be my way of re-inventing myself. But I also try to challenge myself in photography all the time. I do different things, stay with it for a while, but then change it again. It is just that in film there seems to be a far bigger change by the very nature of filming than within my photography. In a way, I always think that the period that I am shooting now is my fifth period and that it is going back to the basics again. There were four periods before that and they were all connected. They were all around the same subject matter, but the approaches vary. Some photographs where documentary-like, others portraiture-like. The black and white ones were almost documentary-like. And the lithprints [a photographic print developed in lith developer that was baptised by Anton a lithprint. This special B/W paper is no longer made] were about portraits. These partly inspired the photo shoots for the self-portraits series [a.somebody, strijen], which were the last version from that specific inspiration. Whereas the paparazzi ones, 33 Still Lives, were a commentary on the world of celebrity. Once I finished that, I went on to see what I wanted with my photography, As my initial curiosity for this as well as for music was kind of finished. Now I am back working as a portrait photographer again since I like the routine and the language of it. You try to meet the person whose work you admire and take a photograph. It is a very basic thing, to go out with a camera and meet somebody through it and take pictures. I think that is what I like in my photography. In that way, and since I started doing film, I have become very attracted to photography again, because in film it is such a different energy and a far more complex way of creating the work, that it becomes really appealing to go back to the very simple art of photography.

LR -- For the 'stripping girls' project, which you created with painter Marlene Dumas, you were acting on some premises which remain true for your work ever since. You repeatedly stated that you neither wanted to create documentary nor glamorous images. What choice is there "in between" these genres? And what is the importance of this alternative way of seeing?

AC -- Well it is almost like an arranged reality. So the approach is almost a documentary one, and yet it is not. I always arrange something in order to make a better photograph, and so I can have more influence on what happens in front of my camera.

LR - Avedon once said: "Photography is always a lie even if an accurate one". Your photographs exude a certain quietness, beauty and intensity which makes them outstanding in my opinion. Thank you for the interview.