Esther Starobin sits in her open dining room and smiles. She has short, gray hair and brown eyes and wears only a hint of makeup. Her simple but elegant outfit consists of blue jeans and a black sweater, accompanied by small, silver earrings that sparkle when they catch a ray of light. Starobin is surrounded by numerous paintings, pictures, posters, masks and small figurines from all over the world that bring life to the quiet suburban house where she has lived for over 50 years. When Starobin talks, her hands are in constant movement -- small, frequent gestures, like rubbing her eyes or warming her hands on her teacup. From time to time, she rests her hands on her cheeks and closes her eyes for a couple of seconds. The way she frames her face with her hands gives her an angelic, almost Madonna-like posture.

Esther Starobin sits in her open dining room and smiles. She has short, gray hair and brown eyes and wears only a hint of makeup. Her simple but elegant outfit consists of blue jeans and a black sweater, accompanied by small, silver earrings that sparkle when they catch a ray of light. Starobin is surrounded by numerous paintings, pictures, posters, masks and small figurines from all over the world that bring life to the quiet suburban house where she has lived for over 50 years. When Starobin talks, her hands are in constant movement -- small, frequent gestures, like rubbing her eyes or warming her hands on her teacup. From time to time, she rests her hands on her cheeks and closes her eyes for a couple of seconds. The way she frames her face with her hands gives her an angelic, almost Madonna-like posture.

"My sister Bertl doesn't call herself a Holocaust survivor," says Starobin, 76, taking her red glasses off. She won't put them on again until she has finished telling her story almost two hours later. "She says we weren't in a camp. But you know what? I lost my parents. I lost my home. I was resettled without having a say in it. That seems to me as pretty much being a survivor."

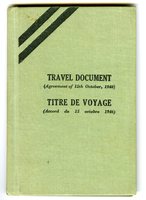

Esther Starobin was born in Adelsheim, Germany, in 1937. Her parents were among the 6 million Jews killed during the Holocaust. Starobin, her three sisters and her brother survived because their parents were able to send them to safety in time.  Starobin left Germany for Great Britain in 1939 as part of a special rescue of Jewish children known as the Kindertransport, or children's transport. At the time she was 26 months old. In England Starobin lived with a loving Christian foster family, and in 1947 her sisters brought her to the United States, where she has been living ever since. Starobin, a mother of two, worked as a teacher for 29 years. Today she is a very active retiree who is engaged at her local temple, knits and crochets enthusiastically, and takes college classes for seniors. For almost 20 years she has also been a volunteer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Starobin left Germany for Great Britain in 1939 as part of a special rescue of Jewish children known as the Kindertransport, or children's transport. At the time she was 26 months old. In England Starobin lived with a loving Christian foster family, and in 1947 her sisters brought her to the United States, where she has been living ever since. Starobin, a mother of two, worked as a teacher for 29 years. Today she is a very active retiree who is engaged at her local temple, knits and crochets enthusiastically, and takes college classes for seniors. For almost 20 years she has also been a volunteer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

The septuagenarian Esther Starobin defies her age with energetic behavior and youthful language. She always holds herself very straight and has furnished her house in Maryland tastefully, with the fall decoration on the dining table mimicking the bright October day outside. At the same time, she uses words like "okey-dokey" to confirm a meeting, regularly checks her Facebook account and keeps herself more than busy.

"I don't think my days are typical," Starobin says to the distant sound of a dog barking in the suburban neighborhood. But they all start the same: with a phone call from her daughter Judy. Judy calls on her way to work, so Starobin has to get up before 7 to be awake for the call. Then she herself calls her oldest sister Bertl, the only other of her four siblings still alive. "Then I have breakfast," Starobin says. After that the similarity of her days ends. The retired teacher attends college classes on Tuesdays and Wednesday, goes to weekly choir practice, exercises regularly, meets her friends for a wide range of social activities, and runs a few committees in her temple. "And sometimes I clean," she adds with a chuckle on her lips.

The past is present in Starobin's everyday life, but her memory crystallizes in subtler ways than one might think, for example in her passion to work with her hands.

"I have always found it very soothing and relaxing," she explains while using said hands to embrace one of her knees. "I used to embroider. I knit and crochet. I do a little quilting." Starobin learned needlework in England, and it is a skill that has proven itself essential throughout her life. In a short story she has written she calls it "something that saved me" -- saved her when she first came to the U.S., when her daughter Deborah was sick, or whenever there was some sort of crisis in her life. "It kept me occupied, and it gave me a purpose, I guess. It was doing something worthwhile," she explains. "And it reminded me of my happy life in England."

Betsy Anthony, a scholar at the Holocaust Museum, has worked with Starobin over the course of the years. They first met over a decade ago, when Starobin started participating in "The Memory Project," a memoir-writing workshop for Holocaust survivors. Today Anthony describes her as "a very thoughtful, caring, and warm person who is very down-to-Earth. She believes deeply in Holocaust education, but she's also someone you can talk to about many other things." However, her most lasting impression of Starobin is her apparent connection to her past. "I can see that little girl in her," Anthony says.

Betsy Anthony, a scholar at the Holocaust Museum, has worked with Starobin over the course of the years. They first met over a decade ago, when Starobin started participating in "The Memory Project," a memoir-writing workshop for Holocaust survivors. Today Anthony describes her as "a very thoughtful, caring, and warm person who is very down-to-Earth. She believes deeply in Holocaust education, but she's also someone you can talk to about many other things." However, her most lasting impression of Starobin is her apparent connection to her past. "I can see that little girl in her," Anthony says.

This becomes obvious to everyone who spends time with Starobin, especially when she talks about the food her British foster parents cooked: "They were big on vegetables," she says while rolling her eyes -- in the same voice children all over the world use when they complain about their parents forcing them to eat vegetables. Or when she recalls how her late sister Edith used to call her "a spoiled brat" who "would act up" if the sisters didn't spend their vacations together. "She made that up! It's not true," Starobin exclaims. Again, her voice suddenly sounds like that of a little girl. Then Starobin starts laughing whimsically, and a moment later she is back to being her 76-year-old self.

Starobin was born in the spring of 1937 in the small town Adelsheim in Germany, about 60 miles outside Stuttgart. Her parents, Adolf and Katie Rosenfeld, sold feed and other products for cattle, and they had four more children: Bertl, Edith, Ruth and Herman. There exists a black-and-white picture of baby Esther shortly before her departure to England. It shows an animated and wide-eyed 2-year-old with dark, unruly curls and a stuffed dog. Besides a couple of letters from her mother and the stories her sisters have told her, that is the lone connection Starobin has to her birthplace. "I really don't remember anything from Germany," she says. "And I absolutely don't remember my parents." Both of them were killed in Auschwitz. Starobin didn't learn the actual date -- Aug. 14, 1942 -- until much later, when her sister somehow found the transport list in a French book.

As sad and tragic as Starobin's story is, she doesn't pause, and she doesn't get emotional telling it. It is obvious that she has talked about it many times before.

In March 1939 her three sisters went to England on the Kindertransport. Esther herself followed in June. Prior to the outbreak of World War II, almost 10,000 Jewish children were rescued from Nazi Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland via the Kindertransport. In Great Britain the children lived in foster homes, hostels and schools.

Little Esther was placed with Dorothy and Harry Harrison, whom she called "Auntie Dot" and "Uncle Harry," and their 9-year-old son Alan in Thorpe, Norwich. "I was very happy with them," Starobin recalls, smiling every time she mentions their names. "I was very much a part of their family."

Little Esther was placed with Dorothy and Harry Harrison, whom she called "Auntie Dot" and "Uncle Harry," and their 9-year-old son Alan in Thorpe, Norwich. "I was very happy with them," Starobin recalls, smiling every time she mentions their names. "I was very much a part of their family."

Her three sisters lived in different parts of England but visited her regularly. Then, in 1947, Esther's oldest sister Bertl followed the directions of their late mother and arranged for all of them to live together in the United States. "When you talk to people who were on the Kindertransport, for many of them, their experience in England was God-awful," Starobin says. For her it was leaving her British family that was unbearable. "I probably somehow knew I had to leave at some point, but I didn't really," she recalls. The way she talks about this time makes it obvious how much of a shock leaving England was for the then 10-year-old girl.

At the beginning the sisters stayed with an aunt and uncle. Starobin describes the time living with them as "truly awful," and unlike all the other people in her stories, she never once mentions them by their names. "Everything was different," she recalls while checking the time on her small, black watch. "School that I had loved in England was awful here. I was in a city instead of the country. I had family I had never even heard of." The already difficult situation was further complicated by the fact that Starobin had to adapt to a new religion. The Harrisons had been devoted Christians, and the entire family went to chapel every Sunday. "I didn't know anything about being Jewish when I came here," Starobin says before getting up and turning the lights on. It has gotten dark outside, and the houses of her neighbors are no longer visible.

The living situation improved when Bertl and Edith moved to an apartment with Starobin, then in her teens, and took care of her all the way through high school. Starobin jokes about being raised by her older sisters, but she believes it was "pretty remarkable," explaining, "Think of it: They were young adults trying to make a life in a new country, and they were stuck with me."

They also encouraged her to go to college, an unusual thing for a young woman in the 1950s to do. Again, Starobin finds this "pretty remarkable," saying, "Clearly, if we had stayed in Adelsheim, we wouldn't have had much education." She adds, "You know, there are good and bad things about life."

Starobin studied at the University of Illinois, and after graduation she began teaching at an elementary school. She later changed to teaching at the middle-school level, which she preferred, and she ended her career, after 29 years, as the head of the social-studies department at a middle school. Starobin describes herself as an "outsider" during her own schooldays in the U.S., and she is sure that it impacted her own teaching. "I was always much better with the kids who were not the in-group, with the ones who had a difficult background," she says.

Around Valentine's Day 1958, Starobin met her future husband, Fred Starobin, a Jewish patent attorney. "There was this terrific snowstorm, and I was supposed to go out on a blind date with Fred on a Saturday, and he called up and said, 'You will watch television in your house; I will watch in mine,'" she remembers. "But then he came down on Sunday, and we really hit it off." They got married the same year, and their two daughters, Deborah and Judy, were born shortly after. The way Starobin talks about her beloved husband, whom she calls the most influential person in her life, doesn't make it clear from the beginning that she is a widow. "Fred died a few years ago," she finally discloses toward the end of her story, looking at her wedding band, which she wears facing the inside of her hand. "My life is pretty different now," she adds. "I know I can reconstruct it every way I want, but I am not sure if there is something. I am close to my kids and my sister Bertl, which I like. And I cannot really think of anything that I haven't at least done a little bit."

Family plays, and has always played, an extremely important part in Starobin's life, which is apparent not only in the way she starts smiling every time she mentions one of her relatives but in the collection of family pictures posted on the silver fridge in her modern kitchen. When she talks about family, she doesn't only mean her blood relatives but Auntie Dot, Uncle Harry and her foster brother Alan.

Family plays, and has always played, an extremely important part in Starobin's life, which is apparent not only in the way she starts smiling every time she mentions one of her relatives but in the collection of family pictures posted on the silver fridge in her modern kitchen. When she talks about family, she doesn't only mean her blood relatives but Auntie Dot, Uncle Harry and her foster brother Alan.

This part of Esther's life story has affected Ester's oldest daughter, Deborah Starobin-Armstrong, in positive ways. "Our family was never just a traditional family," she says, and then laughs shortly, in a way that instantly exposes her as her mother's daughter. "It made me understand that sometimes families are bigger than just those directly related to you."

Esther Starobin truly loved her foster parents, but she always wanted to learn about her real parents and her origin. That desire was only magnified by the fact that she cannot remember them at all. In 1989 she returned to Germany for the first time, accompanied by her husband Fred. "I had to see that I didn't come from a black hole," she explains, squinting her brown eyes and rubbing her forehead as if it could help her remember.

The visit to her birthplace Adelsheim allowed Starobin to put images to the stories her sisters had told her, yet it didn't tell her anything new about her parents, and she couldn't feel any connection to the small town. However, in some way the visit helped her find closure.

"I came away knowing that my parents were really never going to be part of my memories," she wrote in a short story for the Holocaust Museum.

Starobin has long finished her tea, and the neighborhood has turned quiet. Once again her hands rest on her cheeks, and the dim ceiling light intensifies her angelic, Madonna-like expression. "The basic thing of losing my parents was not good," she stresses. "But I think it took an amazing amount of love and courage of our parents to send us away. I was also very lucky with the Harrisons. I mean, they truly loved me."

Esther Starobin stands up, puts her red glasses back on, and walks toward her open kitchen. Before she starts heating up her prepared dinner in her modern oven, the Holocaust survivor adds one final thought: "I think in some ways I have been very lucky."

To find out more about the history of the Kindertransport, visit kindertransport.org.

All photos and documents © U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Esther Starobin