When a child dies, the first place that parents, siblings, aunts and uncles often look for comfort is the church.

The church -- the Body of Christ -- will know how to help us. The church will know how badly we hurt -- they've helped hundreds of families bury their children.

The church will be our safe refuge from this blinding storm of grief that has stolen our peace, our sleep, our appetites and our ability to think more than five minutes into the future.

The church -- where people embody the love of the Man who wept at the death of his dear friend -- will weep with us.

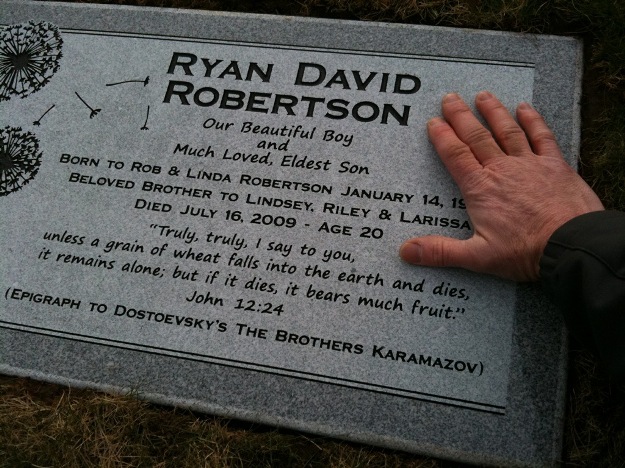

When our son died, it was difficult to get out of bed, much less to get up, get dressed and go face hundreds of people on a Sunday morning. But we did go, because we follow Jesus, and going to church on Sundays has been vitally important to our family.

- Act overly happy and bright, in an effort to cheer us up, or to, perhaps, avoid talking about death.

When our son died, churches were the place where we heard some of the most painful things, many of them from pastors.

Are you better yet?

We heard this one for the first time two weeks after our son's death, and then countless times afterward.

The death of a child is like falling down and scraping your knee.

When this was said to us, one month after Ryan's death, by a pastor responsible for funerals at a large church, we couldn't even respond. We walked away, tears rolling down our faces, and Rob said, "He obviously has never lost a child." I said, "I don't think I ever want to go back to church again. Ever."

This is what your experience will be like: blah, blah, blah.

At this point I always tuned out... the pain was too intense. To be told what we would feel by a pastor who hadn't lost a child, rather than asked what we needed or what grief was like for us only made our pain worse.

Ryan wouldn't have wanted you to be sad!

This was usually said by those who didn't know Ryan well, or how he would have completely understood our tears. And it always made me feel like the person speaking was really the one who didn't want me to be sad... or to be honest.

I know exactly how you feel.

This was typically followed by examples of how the person had lost a parent, grandparent or once, a pet. Nobody knows exactly how someone else feels, no matter how close you are. We would never say this to another family who lost a child, even if that child was 20, gay, struggled with addiction, depression, Hep C and recent hearing loss, and was named Ryan. Every child is unique, and every death is unique.

Be glad! He is an angel now, watching over you for the rest of your lives!

Aside from the fact that I don't think this is the way Heaven works, it does what so many trite phrases do: it invalidates our grief. It communicates that we should be happy, not sad. It can make us think that it isn't okay for us to be honest about how we are overwhelmed by sadness.

In the four years since Ryan's death, I have heard the stories of far too many grieving families who have found not comfort, but only more pain, by attending church after the death of their child. I don't think it has to be this way. I don't think it should be this way.

If I had ten minutes to tell pastors, priests, teachers and leaders what to say to grieving parents and siblings, this is what I'd say:

Ask them what their grief experience has been like.

Allow your parishioners to teach you about grief and loss, and to let you know what they need. Please, please, ask them questions about their grief, and listen without interrupting.

Say their child's name.

How are you feeling about Annelise? What do you miss most about Matt? The power of hearing your child's name after they have died is enormous. Most grieving parents fear that their child will be forgotten and that their child's life and death will not matter.

Our oldest son had been gone for about seven months when someone at church pulled me aside and gently asked, "How are you feeling about Ryan?" I wept with gratitude and relief. I didn't realize until later that it was the first time I had heard Ryan's name at church since his funeral. Just the sound of his name -- the acknowledgement of his life, his existence and his value were like a soothing balm to my soul.

Let them know that they are welcome no matter how terrible they feel.

If we feel we have to force ourselves to act happy just to come to worship, we're likely not to come. When we are feeling our worst, we need God the most. Please allow us to find Him in community with others, even when we are miserable. Even when we're not sure if life is worth living.

Tell them that there is no timeline for "getting over" a child.

Parents who have lost a child - if as a newborn or a middle-aged adult -- desperately need to know that there is no expectation to "get better" in six months, one year, five years or ever.

Reassure them, if needed, that God can handle all their questions, doubts and anger.

Although my husband has only felt closer to God since Ryan's death, after about six months, I began to struggle with a lot of questions that affected my faith deeply. I didn't need answers -- only permission to wrestle through my doubts and fears with God. Remember, too, that asking questions, doubting and not attending church don't mean we are walking away from God -- quite the opposite. Please trust Him to meet us in our pain. He has, and He will.

Listen... without having to provide solutions. And then listen some more.

Unless you are Jesus Himself, you will not be likely to be able to bring their child back. And that is the only thing that would alleviate their intense sorrow. So don't even try to fix anything. You can't.

Know that grief -- and tears -- demand to be felt and experienced.

The research all points to the same thing: if one doesn't acknowledge and make room for their grief, their grief will find another way to express itself. Alcoholism, health problems, rage issues, marital problems, mental health concerns and a myriad of other stress-related problems can all be the result of "stuffing" grief inside in order to make others feel more comfortable.

Teach your congregation to keep reaching out to the bereaved, even if they don't know what to say.

In the "club" of parents who have lost children, almost all of them have also lost many friends as well. Friends who used to be close never call or come by anymore. It makes the experience all the more painful. Remind friends that they don't have to have the perfect words. Often the most comforting thing to hear is, "I don't know what to say." Or, "I just cannot begin to imagine what you are going through."

Know that birthdays and anniversaries of a child's death are particularly painful, but immensely important.

A simple way to let a grieving family know that you haven't forgotten them -- or their child -- is to make a note of their child's birthday and the anniversary of their death on your calendar, so you'll be reminded to send them a card, leave them a voice message or shoot them a text. On Ryan's would-have-been-24 birthday, our pastoral staff sent him a birthday card, complete with personal notes to him telling him how his life has impacted them. It was one of the most comforting, honoring things anyone has ever done for us since Ryan's death.

Remember that by bringing up their dead child, you won't remind them of anything they aren't already thinking about.

Some well-meaning friends avoid talking about the child, because they don't want to make the grieving family cry. But truly, we can hardly think of anything else -- especially in the first months and years. It is only comforting to know that other people remember, too. And our tears aren't bad... they are necessary. They are healing.

Ask about their child.

Get to know him or her by asking about favorite memories, what they were like, etc. This is especially important if the child committed suicide or died as a result of addiction. Grieving parents of kids who struggled feel especially alone, and often sense judgment and condemnation of themselves and their child. Please acknowledge to beauty of every child's soul, not just those who were successful in the world's eyes.

Recently, Anne Lamott was asked what job she'd like if she wasn't a writer. Here is an excerpt from her response:

I'd like to sit out in the very quiet courtyard at St. Andrew Presbyterian, with a bowl of cherries, and a bowl of M&M's as communion elements, and talk to people one at a time.

If people were grieving, I would sit with them while they cried, and I would not say a single word, like "Time heals all," or "This too shall pass." I would practice having the elegance of spirit to let them cry, and feel like shit, for as long as they need to, because tears are the way home--baptism, hydration--and I would let our shoulders touch, and every so often I'd point out something beautiful in the sky--a bird, clouds, the hint of a moon. Then we'd share some cherries and/or M&M's, and go find a little kid who would let us swim in his or her inflatable pool. I'd tell the sad person, "Come back next week, I'll be here--and you don't have to feel ONE speck better. It's a come-as-you-are meeting, like with God, who says, "You just show up, my honey."

This says it all: just giving permission for people to show up, knowing that someone will just be with them, allowing them to feel exactly how they are feeling. Sitting with a friend in their sorrow is the greatest gift we can give to someone in pain. Allow us to be sad as long as we need to. It is in that sadness that God meets us, and that He, slowly, redeems and restores our souls. We will never "get over" our dead child, nor do we want to.

But if we can be patient with ourselves and with God as we heal though the pain, He will help us not to get better, but to be better.

Linda blogs at JustBecauseHeBreathes.com.