Here are the seminal moments of a typical 1980s coming-of-age in America -- those instances when something happened, and we would all remember for the rest of our lives exactly where we were when it did:

•Space Shuttle Challenger crash -- loudspeaker announcement during yearbook class; jaws drop, arm-hairs stand on end; we all cry and hug.

•John Lennon is shot -- my best friend's basement rec room; time stands still while the radio deejay's voice falters; we all cry and hug.

•Team USA beats the Soviets in ice hockey at the 1980 Winter Olympics -- watching TV with my parents, brother and swim team friends in our newly-carpeted family room; sudden eruption into fanatical cheering; we all cry and hug.

Even then, at the age of 10 -- and no matter that that was probably the first hockey game I'd ever watched -- I knew that that victory meant so much more than just a normal win. And USA's subsequent gold medal -- cinched in the final game against Finland -- meant more than any gold medal that had ever been won before, or that would ever be won again.

The American underdogs taking down the indomitable Soviets on ice meant that everything I'd learned in school and from my parents and in our society was right: we were better than they were. Our way of life was superior to theirs. We were the good guys. And, in the end, the good guys would always win.

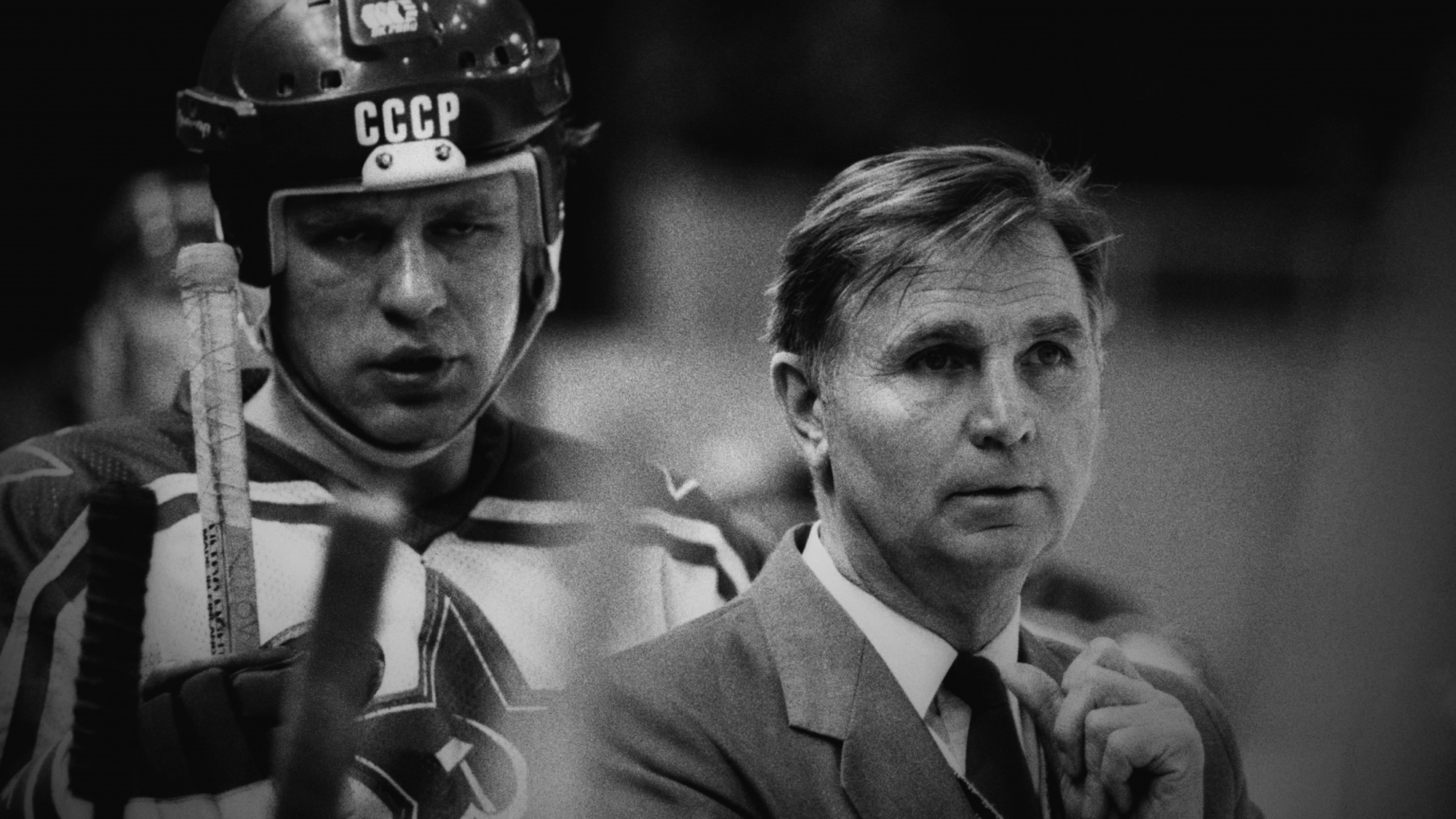

Gabe Polsky's riveting and important documentary Red Army, about the history of Soviet hockey and, more intimately, about the professional and personal journey of Slava Fetisov -- the all-around superstar and eventual captain of the Soviet national team -- commences with vintage footage of Ronald Reagan warning us: in the film we are about to watch, he cannot promise that good will triumph over evil.

Cut to Slava Fetisov himself -- giving director Polsky the finger while attending to more important matters than the interview, namely examining his mobile phone for texts. Who is this cocksure Russian, flipping not only Polsky but also it seems the rest of us the bird?

And still it makes us laugh. (Or at least it made me laugh.) Throughout the film, Fetisov, the ever-amiable grouser, delivers one after another unintended (or are they?) hilarious one-liners, each one of which begs the question: if Fetisov was one of the bad guys, why does he seem so good? Not only so witty, but so determined, so principled, so wise... and at least on the ice -- so damn talented?

What's even more confusingly delightful or delightfully confusing about this film: Fetisov's saga -- his rise from nothing to something extraordinary to banishment to triumph all over again -- plays out like the ultimate "American" story. And yet our hero could not be any less American -- in his style, demeanor and downright brutal wit. One of my favorite lines from Red Army is Fetisov's cavalier denigration of American hockey -- "There's no style. They're so simple. They're not creative."

It's as if he's dismissing the whole country -- our whole country that is -- as a confederacy of simpletons; the hockey rink serves as a metaphor to make this -- insulting, yes, but also kind of apt -- point. The Soviet "Red Army" team's original coach Anatoli Tarasov consulted the Bolshoi ballet for training techniques, and chess master Gary Kasparov for strategy. Most of the footage of American players on-ice shows them clumsily beating the crap out of each other with their fists.

But Red Army is a documentary about so much more than just hockey. It's a window not just into the world of elite athletes, but also into the Cold War -- its oppression, its defections, its KGB trickery, its era of indefatigable distrust and ever-simmering antipathy between them and us. More importantly, Red Army is not just about Soviet stature, power and propaganda; it's about all of those things in Russia today.

At the premiere I attended in Manhattan in early October, for which Fetisov and his wife were almost denied a visa to be there, the theater was crawling with prototypical FSB (Russia's successor to the KGB) agents. (As a former CIA operative, suffice it to say it takes one to know one.) Something about the event felt like traveling back in time.

At the end of the film, which left me exhilarated -- on one level, it's just a feel good sports story -- there was a question and answer session with Fetisov and Polsky.

The banter and interplay between the elder sportsman and the young director was as entertaining in person as it had been in the film. But no sooner had the Q&A got going then it was interrupted by Vitaly Churkin, Russia's ambassador to the UN, who approached the stage and insisted upon Fetisov handing over his microphone.

First, in typical bullying Ruskie fashion, Churkin dismissed Polsky's thorough and brilliantly executed achievement with a denigrating comment along the lines of: So you take one of our greatest sport heroes and weave his story with a little archival footage. It's not so impressive. Meh. Then Churkin proceeded to take Polsky to task for what he considered an unfair representation of Joseph Stalin in the film. The Americans in the audience were looking around incredulously: is this happening? Is this guy really up there defending Stalin?

No sooner had the (seemingly imperturbable) Polsky started to respond to Churkin's criticisms than Slava Fetisov grabbed Polsky's microphone! "Oh Gabe you're so boring," generating heartfelt but slightly uncomfortable laughter from the crowd.

Tellingly, the event ended with both Russians holding mics that they'd stolen, and the American director silenced. To his credit, Polsky must have interpreted the film's ruffling of Churkin's feathers as a victory; he concluded by empty-handedly fist-pumping the air.

I've often described to my kids -- boys ages 7 and 9 who, like me, have turned into avid hockey fans -- the importance of that game at Lake Placid back in February of 1980. They don't get it. They don't understand why one game meant so much. If I try to explain to them about the Cold War -- when we huddled beneath our school desks during bombardment drills, and lived in abject fear under the specter of nuclear war -- they still don't get it.

They're growing up with a different generation of "bad guys," even more sinister in appearance and intent; guys with whom America would never entertain the notion of playing ice hockey.

But sometimes when they ask me, "What was the Cold War again Mom?" I think about Russia today, and Putin, and how his topless imperialistic posturing that used to seem like a joke is becoming less and less funny. And it's times like that when I say to them, "Just wait guys, the Cold War is coming around again."

If the premiere of Red Army that I attended in New York is any indication, it won't be long. This is a film that every American should see before that time comes.

Photos © 2014 Polsky Films, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics