Now that the Los Angeles Times is being orphaned by its corporate overlords, it caused me to think long and hard about this terrible business I've been in now for upwards of 50 years.

First there was the personal shock. On many occasions back in the good old days, I used to prowl the long hallways of the Times' building because I was doing a lot of writing there. And even today I enter into the hallowed halls of the giant building on First and Spring streets and all around me I see the devastation of a war against the newspaper. Its amazing how the same hallways feel so different in different eras. Things have been on a downward spiral ever since the Chandler family sold the paper to the Chicago Tribune in 2000.

Back in the '60s, the cityroom reeked with a sense of confidence. True, even back then oldtimers were uncomfortable because publisher Otis Chandler had allowed his mother "Buffy" to remodel the city room so it looked like an insurance company's executive offices. No longer could you throw your cigarette butts on the ground and grind them into the floor with your soles and heels. The carpeting was corporate luxurious, and ashtrays and private places to hide your hooch were conspicuous by their absence.

Of course the colorful characters who used to populate cityrooms are long gone, and with them a lot of good writing is gone as well. In those earlier days, reporters didn't go to universities to learn how to write. Often they came to journalism by way of being taxi drivers, merchant marine sailors and bartenders. Today's journalist are cookie-cutter types who sip Pierre and write their indistinguishable prose. In fairness, the rimrats and wild men of yore appreciated what Otis Chandler was doing with the Times, trying to make it into the greatest newspaper in the country. The excitement was palpable.

But the battle was lost long ago. Today's editorial peons slink and scurry about because they know the grim reapers from corporate are drawing up the next list of writers to "trim and prune" in their ever increasing drive for editorial "efficiency."

The newspaper has become an interloper in its own home. The radio stations and television stations purchased with the huge profits of the newspaper over the decades have now been lumped with the real estate into the main corporate entity, and a separate unit with the newspaper itself has been spun off. They pretend they are salvaging the newspaper by condemning it to death.

Now the newspaper must pay rent in the building paid for by the newspaper's profits. If editorial want to use a conference room at First and Spring street, they have to pay extra for it.

When I first started freelancing for the newspaper in the '70s, I was joining an opulent operation that had set out to become a rival for the New York Times nationally, and a great newspaper in its own right. It had twice the circulation and staff than the version that's produced nowadays. It also had some really top rate writers -- people like Ruben Salazar and Bella Stumbo, Jack Smith, John Pastier and many others. The paper now has no style, little wit, no real vision or purpose. It's just going through the motions until it doesn't. There may be talented individuals among the minions -- I know there are -- but there's a demoralization evident in its pages that's hard to miss.

I came into the business at a tumultuous time in journalism. It was early in the '60s and the underground press was in full bloom, driven in part by technological changes such as cold type and offset printing. Both were much cheaper than the old clanking linotype machines and gigantic presses that squeezed the images on newsprint from a half circular plate of lead. The civil right movement and then the Vietnam disaster drove the Underground Press. I was one of a group of four journalists from the Los Angeles Free Press, recruited to write for West magazine in the Los Angeles Times. As a result of the new printing technologies, and the so-called new journalism, the Free Press was able to gain a large and influential readership. The new journalism was but the descendant of the kind practiced by Mark Twain.

Cold type and offset printing were almost as important to alternative journalism as the Internet is today.

The difference also was the people. Charles Bukowski was probably the most talked about writer in Los Angeles, and he was in the Free Press, not the Times. My generation of journalists learned by mentoring, not going to university. You learned from old hands. You learned to drink with them and either the cityroom or the closest bar was your classroom.

Academia by its very nature worships authority, whereas a journalist must constantly probe and question conventional wisdom. While newspapers increasingly hire their staff through their human relations departments, the way journalists got hired in the old days was totally different.

At the San Francisco Chronicle, the city editor would ask potential reporters to show him not their news clippings, but the manuscript of the novels they were working on. If you weren't working on a novel, you weren't the right material. The tradition did not lean to the establishment, as today's generation leans, but toward revolution, enlightenment and science and democracy. Paine and Twain were scribblers whose mighty prose was issued forth from places that had printing presses -- for that's what newspapers used to be, sort of the collateral product produced by printing shops where you got your wedding announcements produced. Paine and Twain both handset their articles with lead type.

It was with good reason that one of my greatest mentors, Scott Newhall, the genius editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, refused to hire anyone who had a journalism degree. "Degrees in history, literature, philosophy, psychology are fine," he used to say, but he figured that journalism schools beat anything original and insightful out of its graduates.

There's another thing that has changed over the years. Newspapers used to be fun. For many of my earliest decades in the business, I looked forward to going to work. The cityroom was the vortex of a community, where everything was happening. West magazine had its auxiliary cityroom in the Redwood Room, which in those days was actually in the Los Angeles Times building.

Scott taught that true journalists are "a priesthood, dedicated to unveiling the truth." He thought that a good paper should educate and entertain and amuse. It should be fun to read as well as informative. That spirit is totally gone now in contemporary journalism, which essentially has turned newspaper city rooms into word factories, where the peons are grateful for their shrinking paychecks and crank out the drivel needed to pour around the ads.

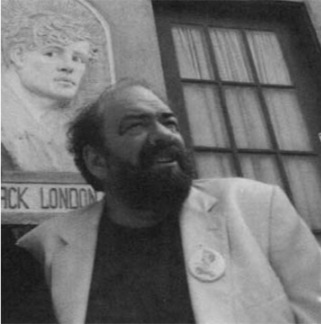

Lionel in front of a bas relief of Jack London, when he was younger and journalism was a hell of a lot better. Photo copyright Phil Stern.

The changes are not just technological. Part of what's wrong with contemporary journalism is that it's bland and like a lot of things that are bland, the deeper message of bland is evil.

Lucifer is not necessarily a colorful guy. Nowadays he's probably a marketing guy. About the time that the underground newspaper movement was growing, there was also a corollary phenomenon going on amongst the overground paper. Most papers were owned by families or individuals. Because of tax laws, most of those families ended up selling out to corporations, who put out newspapers in places like Duluth and Norwalk from Imperial corporate headquarters elsewhere. Papers became homogenized, alike in every town. Newspapers used to be run by proprietors, or later the families of the proprietors. It wasn't always good but it wasn't corporate. Newspapers had character, just like the towns they spoke to had character. Today newspapers are owned by people who not only know nothing of the "business" of newspapers, but also nothing of the nobility and primacy of the printed word. It is these scoundrels who have stolen journalism's soul.

Lionel Rolfe is an author and journalist who has written various volumes on classical music, literature, journalism, history and philosophy. His one novel, The Misadventures Of Ari Mendelsohn: A Mostly True Memoir Of California Journalism, is available in print and digitally at Amazon.com.