For years, I lived in constant fear that I would inadvertently kill my own child.

It wouldn't have taken much.

A simple error in judgement or an innocent miscalculation could result in life-ending consequences.

In 1996, my son, Albert, became one of the 40,000 Americans diagnosed each year with Type I Diabetes (T1D). Not so long ago, that diagnosis would have been regarded as an immediate death sentence. Still, the National Institutes of Health states nearly seven percent of T1Ds will die from the disease within 25 years of diagnosis. My son was two and a half when he was diagnosed. That means he has a one in 14 chance of not making it to his 28th birthday.

Currently, 1.25M Americans are living with T1D.

By 2050, that number is expected to grow to five million.

When Albert was a toddler, he developed the stomach flu, a common ailment for a young child. However, this time was not so typical. He couldn't keep even an ounce of fluid down. His eyes were sunken and he was rapidly losing weight. Soon, he became lethargic and dehydrated, so off to the doctor we went.

I'm the kind of mother who mentally runs through a list of possibilities in order to prepare myself. Best case scenario -- he would spend a couple days in the hospital getting IV fluids. Worse case -- meningitis or even leukemia. My mind comprised a checklist of what to do for each potential outcome.

Ordinarily, Albert would run down the hall to greet his pediatrician with a hug. This time, I had to carry him. As we approached his doctor, I saw the smile on her face vanish before she quickly caught herself. I wondered why she kept leaving the room during my son's examination.

I found out later she didn't want us to see her crying.

She announced that he was diabetic and needed to be immediately transported by ambulance to the hospital. Like vicious kicks to my gut, her words took my breath away. T1D was not on my list.

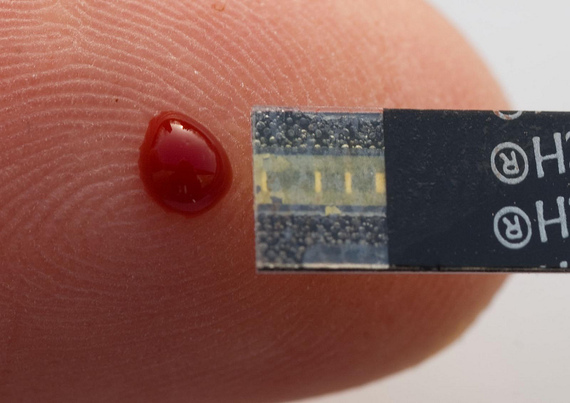

I have come to learn that Albert is considered one of the lucky ones. His pediatrician recognized the warning signs and performed a quick test to confirm her suspicions. Tragically, many doctors neglect to order either a urine dip or blood prick. Just recently, the T1D community was rocked by the deaths of two children whose doctors failed to execute a five-minute test costing less than $1.00. These are the just ones who garnered national attention. There are countless more families suffering this needless heartbreak.

For the next 10 days, my husband and I underwent a crash course in caring for our son. We learned that T1D occurs when the body inexplicably attacks itself and kills the insulin producing cells of the pancreas. He did not acquire it as a result of anything we did or didn't do. We soon realized that controlling diabetes is a life-long, relentless process. It permeates every aspect of Albert's life.

Until there is a cure, T1D can only be managed -- not eliminated.

Through Albert's endocrinology team -- yes, it takes a team to regulate a juvenile diabetic -- we found out that controlling diabetes is much more complicated than simply counting sugar and carbohydrates. Each and every thing had to be monitored and factored into his care plan: What time did he take a nap? When did we plan to eat? How much exercise did he get? Was he on a growth spurt? Could he be catching a cold? We had to be on constant alert for any unexpected spike or drop in blood sugar. Quite literally, all decisions concerning Albert were a matter of life and death.

When you are the parent of a diabetic, you're forced to cohabitate with a beast that threatens to devour your child at any moment.

You can't kick it out. You can't kill it. You can only hope to appease it. Living with this monster mandated that we teach our young son, not-yet-three, to recognize the warnings signs of its fiendish presence.

His warrior training began when he was just a toddler.

From the beginning, we were fiercely determined to consider Albert's diabetes a single part of his life -- not his sole identity. We didn't want him to be labeled by his condition. Once we realized Albert could have a treat now and then, we were ecstatic. He didn't have to substitute carrot sticks for cake at birthday parties. He could be a normal kid.

When it came time for Albert to enter elementary school, I was engulfed with worry. Would they know how to handle his diabetes? Would he be bullied by his peers?

Before meeting with the school, I sat down with Albert's doctor to formulate a plan. She provided me with a list of needs that he had a right to be met. She counseled me on what to say and offered to send a nurse advocate with me. If the school gave me any trouble, they had lawyers on standby to help take our case to court, if necessary.

I came to the meeting loaded for bear. If they didn't accept each and every one of our demands, I was ready for combat. Calmly but firmly, I explained Albert's requirements. When I was finished, the school nurse smiled and sweetly said none of them would be a problem. I sat there dumbstruck, the wind taken away from my sails for a moment.

During his kindergarten year, there were often treats handed out at times that didn't coincide with Albert's snack schedule. His teacher and I worked out a system whereby Albert would bring the treats home to eat at a later time. One day, the teacher had a peculiar look on her face when I came to pick Albert up. "I'm sorry," she explained. "He insisted." She handed me a Ziploc bag filled with chocolate goop; two Popsicle sticks bobbed inside like abandoned water skies. Apparently, the goodies for that day were Fudgesicles.

Most T1D families encounter ignorance and/or opposition on a daily basis.

Albert was blessed to attend compassionate schools that rarely balked at any of our requests. His principals carefully considered his needs when deciding which teachers were up to the task of having a diabetic child in their classroom. He was regularly given the opportunity to speak to the class and explain his condition. After a while, his classmates rarely gave it a second thought.

Sadly, this is not the norm for many diabetic children. Too many parents of diabetics have been forced to challenge educators that are ill-informed and sometimes downright hostile.

Our family has not been spared from encountering ignorance. One parent demanded that Albert not test in the lunch room because she was afraid her child might "catch something." Countless people have asked when he will grow out of it. Others have insinuated that we could make it go away if he abstained from sugar. Sometimes, it's almost comical. Once, while Albert was playing football, he missed a tackle. He took himself out and explained to his coach that he felt "low" -- a common diabetic term for a drop in blood sugar. "Don't worry, son," the coach responded. "Everybody makes a bad play now and then." It wasn't the first, or the last time, a medical need was misinterpreted as an emotional crisis.

We cannot let up in our fight to eradicate this beastly disease.

Today, Albert is 21 and has been managing his own care for some time. He is about to start his senior year of college and plans on becoming a teacher. Together, we have worked hard not to allow his diabetes to hinder whatever he wishes to accomplish. An avid participator in sports since the age of 4, he is currently a member of his school's track team. He works full-time at a children's camp during the summer. Thanks to medical miracles such as his insulin pump, I sometimes forget he has a disease that could suddenly jeopardize his very existence. I am extremely proud that he approaches life not as a victim, but as a quiet, daily conqueror.

Also on HuffPost: