David Hockney in front of Perspective Should Be Reversed (2014), July 15, 2015

Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

Photo Credit: Stephanie Keenan

"Painters have always known there is something wrong with persective. The problem is the foreground (hence Cubism). Where am I? And the vanishing point." - David Hockney, 2015

David Hockney is a fearless innovator who is always ahead of the curve, experimenting with the latest technologies to discover new ways of making images. His curiosity about exploring different ways of seeing is embodied in a practice that combines the dexterity of a draughtsman, the scholarship of an optical science historian and the thrill of a child discovering new things.

Hockney's new work is a playful critique of the limitations of photography, that captures fascinating things a fixed perspective can never capture--multiple vanishing points, altered perspectives, different moments of time, emotional resonances--which keep the eye alive. Seen together, the paintings and digital "photographic drawings" in this exhibition have a coherence that goes beyond individual pieces to retain our interest. Viewed from a close focus, or a distant focus, or from the movements of the eye looking around, across, above and below, we can make visual connections, metaphoric connections and art historical connections between the recurring visual details of the tables, chairs, walls, floors, jackets, shoes and friends who fill the daily life of Hockney's Hollywood studio.

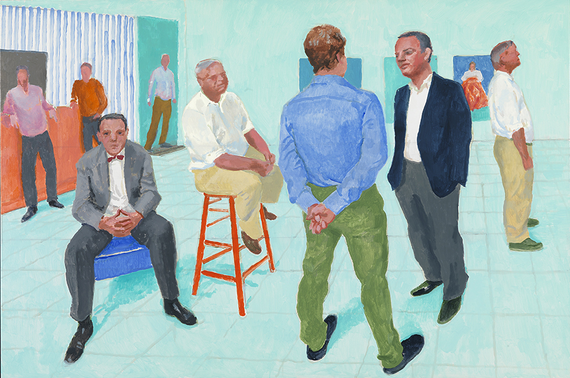

David Hockney, The Group V, 6-11 May, 2014

Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72 in.

© David Hockney, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

Hockney describes his photographic drawings as " 3-D without the glasses" because he digitally collages hundreds of images to make singular compositions which are conceptual puzzles that bring everything into a sharp close-up view--even from across the gallery. Sometimes he draws shadows, blurs details, moves lines on the floor in different directions which are closer to the natural way we look at the real world with our moving eyes while processing visual information.

No other artist has combined high tech and low tech with such elegance: painting using Photoshop, iPad, iPhone, fax machines or collaging using Polaroid photographs. Hockney is a strong advocate of the creative possibilities of optical devices in the hands of artists who can bend perspective, but a staunch critic of the artificiality of fixed perspective photography which dominates visual culture today.

Hockney developed his optical hypothesis in his acclaimed book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters (2001). After twenty years of studying the old masters' techniques and experiments with optical scientist Charles Falco, they uncovered the use of lenses and concave mirrors that produced projected images which artists like Ingres, Van Eyck, Caravaggio, and Vermeer drew upon for greater realism. This is an architectural perspective invented in 1420 by Brunelleschi and adopted later by painters, then by photographers--of a window looking onto the world.

The invention of modern photography is based on these early camera lucidas that great artists used secretly. But without "the hand, heart and eye" of the artist to bend perspective closer to the natural way we see, photography creates an artificial perspective which dominates visual culture today. The problem with this fixed perspective is that the viewer is left out of the picture: nobody actually sees in this disembodied way, where a void separates them from the picture.

David Hockney, JP, JM, JW in the Studio, 2015

Photographic drawing printed on paper, mounted on Dibond

30 x 60 1/4 in., Edition of 25

© David Hockney, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

In these experimental digital works, Hockney liberates the picture from the separating void, bringing the viewer back inside the picture. Impressionist, Cubist and Oriental art are much earlier graphic representations of the relativistic principles of scientific ideas of space and time (from Einstein to quantum physics). But Hockney uses digital technology to further challenge the way photography monopolizes bogus concepts of reality and truth.

The theoretical basis of this exhibition is emphasized in a didactic work, Perspective Should Be Reversed (2014). The title appears in bold letters on a table beside a handwritten note "especially for photography" and T.J. Clark's book, Picasso and Truth, a homage to Picasso's cubist perspectives of interior spaces. In this painting, friends (who reappear in other works) point in different angles to Hockney paintings on the walls. His curator, Jonathan Mills, amusingly stands in the center with arms outreached like an evangelist.

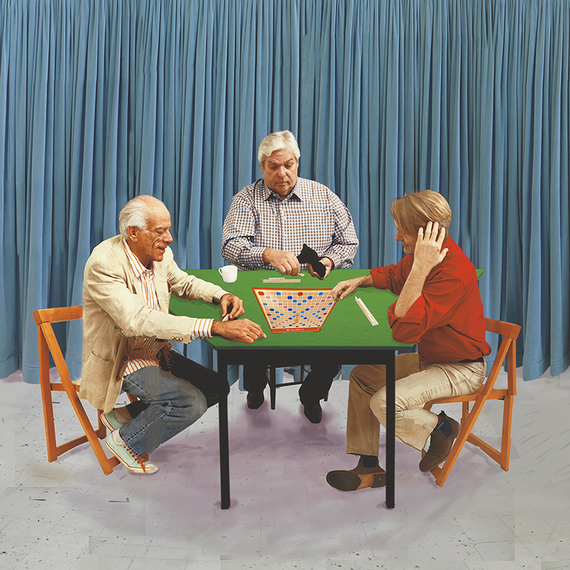

Hockney pays homage to Cezanne in The Card Players (2015) and his own landmark post-Cubist Polaroid collage Pearblossom Highway (1986) appears with less visible joins in digital technology, suggesting his own lineage and progression. The vibrant colors in these new works are an homage to Matisse, who sought more exotic colors to create deeper dimensions of consciousness.

Back Cover, "David Hockney: Painting and Photography" Exhibition Catalogue

© David Hockney, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

Hockney's friends who reappear, even in the series of exquisitely constrained portrait paintings, never appear smiling--which gives them gravitas. His chairs and tables widen into expanding rectangular shapes creating a more inviting "chair-ness" and "table-ness," which gives them weight. This is demanding work which requires thoughtful engagement from the viewer as its raison d'être. Hockney provides a powerful antidote to the mindless consumption of photography--filled with wit, nuanced meaning and the passionate conviction that exciting times are ahead for artists.

A Conversation with David Hockney and Peter Goulds

David Hockney with Peter Goulds (Director, L.A. Louver), July 15, 2015

Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

Photo Credit: Stephanie Keenan

Lita Barrie: It is amazing that our way of looking at the world through images is a complete artifice, but we are so used to it we don't recognize it.

David Hockney: There are thousands of perspectives--not just one--everywhere you look. Perspective doesn't exist in nature. It is just a convention, but it is a convention now that is fixed with photography. When it was fixed with painting, painters could bend it... and did. Painters always bent perspective. But chemical photography cannot, and that has dominated the 20th century. But now we are in the digital age, and digits have much more information.

LB: So perspectives have come a full circle from 20th century photography?

DH: Photography came out of painting. The camera lucidas were used for painting before photography. It is now going back to painting because digits are leading us back.

LB: Why is that?

DH: Chemical photography is a very physical thing. Digital photography need not be physical for quite a while. You can manipulate and do all kinds of things on a screen before you print something. In chemical photography, it always had to be printed.

LB: So there is more room for the human hands, eyes and feelings?

DH: Oh yes, I'm realizing it now. Look--these are my images from four months ago. The table is in reverse perspective.

LB: Even in novels, writing from the singular third person perspective is an artifice, too; it isn't the way we experience a story from our personal perspective or even empathize with other people's perspectives.

DH: There are interesting debates beginning. One in Islam about images of the prophet, because Islam shouldn't have any images, really, if they're strict. Nobody is going to live in a world without images today. Images empower people; images on Facebook, etc. Your friends are now the stars because there is an image of them on a screen, so you are not seeing other stars on the screen. It is all changing.

LB: You challenged Frank Stella in your earlier book, The Way I See It, in the 1980s. Stella thought abstract painting was in a conundrum with shallow surface space, and that is why he turned to sculpture. You challenged him that he had made an error.

DH: Yes, because the question is, what did he think of photography? He thought photography was fine, but I never thought photography was fine--that is the difference. I know what is wrong with photography and now [that] I've got it, I'm playing with it in this new work, Card Players.

David Hockney, The Scrabble Players, 2015

Photographic drawing printed on paper, mounted on Dibond

44 1/4 x 42 1/2 in., Edition of 25

© David Hockney, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

LB: Do you think that when we have more visual spatial depth--as opposed to the shallow surface painting Stella criticized--that gives us images with more emotional depth?

DH: I think there is a link between spatial depth and emotional depth--of course there is. I know that if you printed a normal photograph that size from here, you wouldn't be able to read or see it. When one perspective is set up, it is not good enough, really. That's what I've said before. How could painting go away because of photography? Well, photography isn't good enough, because its main problem is perspective. To pretend there isn't a problem with perspective is to be a bit blind, I think.

LB: So, getting away from artificial fixed perspective opens up more dimensions for art and the role of the artist--more like the role of ancient artists?

DH: Oh yes, it opens loads of things. Cubism was doing it a bit, but that was with things close to us. It hasn't had the influence that the photograph had with perspective, and photography has dominated. Most people don't know the problem with perspective in photography because it is about ourselves more... and most people don't know themselves.

LB: What about the relationship between science and art? My Cal Tech astrophysicist friend, Mamikon Mnatsakanian, explained to me that there is no void or vacuum in space because space is filled with vibrations of energy. If space is always vibrating, I'm wondering if what makes a painting come alive is when it vibrates.

David Hockney, Studio Interior #1, 2014

Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 48 in.

© David Hockney, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

DH: That is vibrating [points to a new studio work]. Cezanne said painting was all vibration.

LB: It's fascinating that they knew to use the sun for solarizing projected images in 1420, because all life is made of vibrations of light. Our bodies are made of vibrations of light, too.

DH: I just do it by instinct. All these new pictures are vibrating.

LB: Do you think people will have a different view of the media when they understand that photography, which we have all accepted as a mirror of truth, is actually based on an artificial perspective?

DH: Photography is just one viewpoint, really, and there is never just one viewpoint--there are always thousands of viewpoints. Photographs are not real or that good. To think the highest we will get with reality is photography is naive.

LB: It is a major paradigm shift. Were you shaken by this radical idea, Peter?

Peter Goulds: It evolved over so much time. It has its roots in the '80s and I was anxious to see where it would go twenty years later... and here we are.

DH: The whole thing about not painting anymore is about photography, really.

PG: Think about how much David has used technology as a device to see his way through even landscape painting, for example. Those wouldn't have been done without the chance to reflect through the documentation of a day's work in the studio that evening and planning the next day's activity. There are a lot of technical issues that facilitated this thinking. So it is a very complex analysis to understand this process of evolution.

LB: David, I enjoyed your book, Secret Knowledge, because it wasn't art history but rather, the history of image making.

DH: Well, art historians don't make images. The problem with art historians is this: a science historian would be very concerned that scientific education was really good and concerned if it deteriorated. The art historian has no interest at all in art education and it has made them look at art too separately.

LB: So these philosophic concepts came out of experimenting with image making in a hands-on way?

PG: That is the difference. Etymologically speaking art means "to make."

LB: The Greeks also said art is based on techne which means technique.

DH: What I've said about Caravaggio, Vermeer and others makes them closer to us now... that's the main thing. Because there was something that looked like an enormous barrier art history set up, and it was their forgotten technical skills.

LB: Do you think there will be more representational, figurative and landscape painting now?

DH: Well, painting cannot die. The French said all their talent went into filmmaking. But paintings don't talk, don't move and last longer.

LB: How do you think this major paradigm shift will influence other artists?

DH: These new paintings will be shown in one long line in the order painted to see they are all paintings of individuals. That is what is happening today; we are all becoming individuals and the "mass" is gone because people are not all fed the same thing. It will have a profound effect.

Guests at the exhibition opening night, L.A. Louver, July 15, 2015

Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

Photo Credit: Stephanie Keenan

LB: Can I ask a more personal question regarding age? I've noticed that as people get older, they become more child-like. I love the combination of a childlike mind with the wisdom of a long life.

DH: When I'm painting I feel I'm thirty. When I stop, I'm not.

PG: I've always thought that one thing that separates artists from the rest of us is that they have a closer connection to childhood, because they don't leave childhood the way we do. Artists within their own time naturally compete with their contemporaries and the battle is internal in this way. Then they get transcendent of their contemporaries, and start to struggle within--overcoming what they can't do and what they want to do. That battle is essential and gets them away from the battle of the time they are in and into a timeless place.

LB: Painters, philosophers, physicists and poets have a lot of affinity because we all prefer to play with questions.

DH: That's why I'm looking forward to my second childhood... or even third childhood.

David Hockney: Painting and Photography is presented in collaboration with Annely Juda Fine Art, London, UK and currently on view at L.A. Louver, Venice, California (July 15-September 19, 2015).