Just a few more weeks left for "Mantegna to Matisse," the current drawing show on view at The Frick collection till January 27. On loan from The Courtauld Gallery in London, where it enjoyed its first incarnation this past summer, and organized here by The Frick's Deputy Director, Colin B. Bailey and Chief Curator, Peter Jay Sharp as well as Stephanie Buck and Martin Halusa, Curator of Drawings at The Courtauld Gallery.

As we delve deeper into the sheer breadth of mark making delight made by masters across Europe, from the late middle ages to the early 20th century, the lines seem to grow more mysterious with the secrets of each respective time and culture. The rooms are filled with the very first thoughts into visions that masterpieces are made from: dreams, impressions, and the use of the forces of love, hate, denial, desire, and urgency in all the right ways. One can almost imagine the traces as well -- of the first match that lit the fire of real raw creation in its own right -- in mythic proportions.

At the very least, one begins to notice the once palpable differences between cultures, as given to us through approach and subject matter in the artworks presented. These idiosyncrasies of spirit have existed (and have quite possibly disappeared) due to a variety of factors in these changing times. Quite clearly the Italians (whose work is represented in the majority, along with the French, in this exhibit) give us love of the domestic, the sublime, and an otherworldly charm that is not at all secular. Nearly half of the 16 works presented move around Christian themes, which we expect, appreciate, and warm up to.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564)

The Dream (Il Sogno), c. 1533

Black chalk

15.6 x 11 inches

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

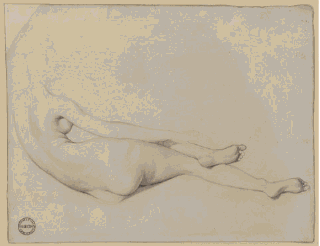

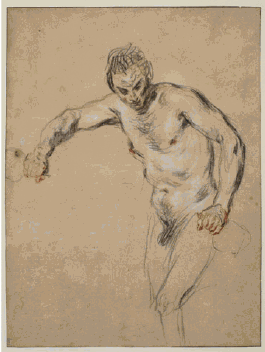

A bold example is Michelangelo's Il Sogno, a youth being touched by the trumpet of an angel above, a man existing in both the real and symbolic realm, at once. The Spanish artists (presented in the minority along with the German and the Swiss) have a keen sense of the bizarre, the intense, playful or wrought. Whichever way it comes, it's always sensational. Here, as in Goya's incredibly zany sketch of floating old women or witches, we see best how metaphysical questions are made into something gorgeous and alive, a moving force in the lines drawn. The French -- with their unmatched gift for a classical and sensual beauty -- from the entrapment of the Ingres in Study for La Grande Odalisque all the way to a Watteau -- with limbs that emanate a sensation close to that of real flesh, as in Satyr Pouring Wine -- something moves under our skin in waves of soft electric motion and doesn't end. The Flemish are a bit hard to pin down, as represented here by a variety of subject matter from Gods and Saints to pearl diving and peasant life. Wild or biblical, the marks at times resemble a precious metal or stone.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

Study for La Grande Odalisque, 1814

Graphite

7.3 x 10 inches

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721)

Satyr Pouring Wine, 1717

Black, red and white chalk

11.2 x 8.3 inches

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

A favorite, shown here in fascinating shapes and an upward sizzle similar to flames, is one of the first depictions of its kind -- referring to the movement of water, in Pieter Bruegel the Elder's A Storm in the River Schelde with a View of Antwerp. The Dutch artists, in a myriad of themes, are equally difficult to plunge into simplicities. We have here moral lessons as in the one given in Death and Lovers by Abraham Bloemaert as well as the hard and fast lines of a Rembrandt that come together to show us something soft and very human. On view as well is Van Gogh's Tile Factory, with marks that seemingly fly in all directions, held together by a centripetal force, and give us space and breathing room. This light touch is not found easily in the artist's paintings. Finally, we come to the British, cool, collected and with tactful reserve -- almost Zen-like -- keeping their emotional reserve hidden in the metaphor of landscape. The most telling (and tumultuous) impress us through the work of the beloved Gainsborough, as well as in the emotive idyllic sources of a Turner.

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828)

Singing and Dancing (Cantar y Bailar), c, 1819-20

Point of the brush and black ink, with scraping

57 x 92.5 inches

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851)

Colchester, Essex c. 1825-26

Watercolor, white and colored chalks, and gouache, with scraping

11.3 x 16 inches

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Differences in culture, as expressed through art, were once immanent and pleasurable. One has a sense that as we move closer and more connected globally, we're nostalgic for the variance that make each country's artistic expression all the more appealing.