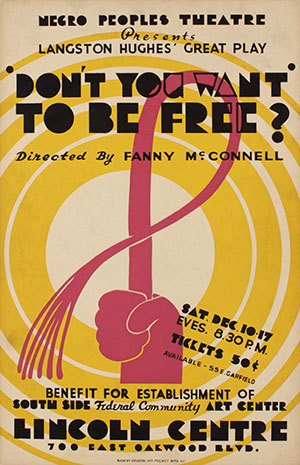

Unidentified artist. Negro Peoples Theatre Presents: Langston Hughes' Great Play, "Don't You Want to be Free?" 1938. Collection of Merrill C. Berman

In 1930s America -- more than half a century after the abolition of slavery -- posters urging "Equal Rights for Negroes" and asking Langston Hughes's famous question "Don't You Want to Be Free?" drew attention to the continuing struggle of African Americans to secure their rights as citizens. Decades after these posters appeared -- and a full year after the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act -- Lowndes County, Alabama, whose population was eighty percent black, still did not have a single African American registered to vote.

With disappointment and fresh anger, across the South and throughout the country, came a new poster. Featuring the massive claws and sinuous body of a jungle cat poised to attack, the poster signaled the willingness of at least some African Americans not just to request or demand their rights but to claim them by force if necessary. It was an image, and a message, that attracted many to the Black Panther Party.

Posters such as these have their own history and tell us much about the history of social and political movements in the United States, as demonstrated by a new exhibition of graphic art from the collection of Merrill C. Berman at the New-York Historical Society. The exhibition reminds us of the powerful tools of persuasion that American artists have used to galvanize movements of social protest, including opposition to racial injustice, and perhaps opens a new perspective on the images of violence that are circulating today.

The exhibition begins in the Depression era and continues through the end of the Vietnam War, showing how American graphic artists drew on European models that developed in the 1920s to fight fascism or promote revolution. The artists often used brilliant colors and bold linear effects to produce artifacts that were ephemeral in themselves but might, it was hoped, inspire lasting change. Posted on walls and bulletin boards and slapped up on store windows and church doors, these memorable, quickly produced images served as the wallpaper of public discontent.

Many of the best-known images in the exhibition date from the 1960s and early '70s, when the artistic strategies of the 1930s, originally developed by the radical left, were adapted for use by other social and political movements. Anger against racism, demands for armed resistance to the draft, fury against elected officials and calls for autonomy by communities of color were kept in front of the public on posters and cheaply printed broadsides and became part of a general social turmoil.

Although the overwhelming fact of the Vietnam War absorbed much of the energy of social protest during this period, a major strain of these activist images and messages focused on a sense of embattlement in the black community and the desire of many African Americans for forceful resistance. One well-known poster in the exhibition, for example, shows Huey P. Newton, a founder of the Black Panther Party, enthroned in a wicker chair, weapons in hand, with shields flanking him as if to protect black Americans from official violence. But as the posters in the exhibition document, such images evoking the antagonism between African Americans and law-enforcement authorities became part of a visual culture that reflected the increasingly toxic environment between protestors in general and the police.

The exhibition includes posters dedicated to the memories of Bobby Hutton, a teenage member of the Black Panthers who was killed in Oakland, California, by police in 1968, after protests set off by the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and of Fred Hampton, the Illinois Black Panther leader who was shot to death in his bed by Chicago policemen in 1969, at age 21, in a pre-dawn raid. There is also a poster featuring images of members of the Ohio National Guard firing on and killing anti-war student protesters at Kent State University in 1970. In all of these cases, the graphic imagery helped to arouse public anger and channel support for the cause. More than 1,500 people attended Bobby Hutton's funeral, and his name became a rallying cry not only for Party members but for others in the protest movement. Hampton's death outraged a wide range of citizens, from black Chicago police officers to college students to establishment liberals. The Kent State shooting has been called the "turning point" in the Vietnam War.

Where do we find such images today? New-York Historical's exhibition observes that American graphic art has now largely been replaced by graffiti, online postings and social media. Still, it is arguable that there is a direct line from the images crafted by artists of the past and the videos captured by ordinary citizens today. Look, for example, at the poster in the exhibition that depicts Bobby Seale's 3-year old son, Malik, brought to witness his father shackled and gagged in the courtroom at his 1969 trial in Chicago. Compare the effect to the impact of the widely circulated videos of Rodney King being beaten by Los Angeles police officers, or Eric Garner dying with the words, "I can't breathe."

It is possible that the overwhelming similarities among such images across the decades might contribute in part to the conclusion drawn by some observers that brutal, physical coercion of black people, endorsed, in their view, tacitly or explicitly by the white majority, is part of the American DNA. This is part of the argument made by author Ta-Nehisi Coates in his new best-selling book Between the World and Me, in which he instructs his 14-year-old son, "Here is what I would like you to know. In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body -- it is heritage."

If a tradition of images has embedded that perception, will new images, made possible by recent technologies, help to change the picture? Several important differences between graphic art and new technologies such as cell phone videos suggest this could be the case. Anyone can make or take a video, unlike graphic art. And the real-time testimony of videos, unlike the single message of posters, allows for a much more informed public debate and discussion of what actually happened or did not happen. Recently, New Jersey's Acting Attorney General John Hoffman announced that New Jersey State Police would spend $1.5 million to equip 1,000 troopers with body cameras. "Body cameras," he said, "will act as an objective witness in police-involved shootings and other use-of-force incidents, so that truth rules the day, not emotions, not agendas and not personal bias." We will soon see whether these technologies make good on the promise of transparency and accountability, distancing us from the less subtle images that formed the "wallpaper of public discontent" of the past.