The title of the world champion is a frequent topic of conversations about chess and bringing in Magnus Carlsen is inevitable these days. But did Carlsen do anything unique to win the title?

The dagger, ending Vishy Anand's hopes, came in Game 9 of the World Championship match in Chennai last year. It sealed Carlsen's victory, although the match officially finished after the next game with the score 6.5-3.5.

Anand (photo above) was a great world champion, having successfully defended the title many times before. Game 9 was his last chance to mount the last offensive and 100 million television viewers in India were watching. Few days earlier their beloved cricket player, Sachin Tendulkar, retired and they wanted Vishy to carry the torch and make a comeback.

But something extraordinary happened during the game. Being pushed back, Carlsen spread all his powerful pieces on the edge of the board and with his kingdom on the baseline, he sent forward a single pawn to do battle. The little foot-soldier won the war against Anand. Carlsen became the ultimate baseliner.

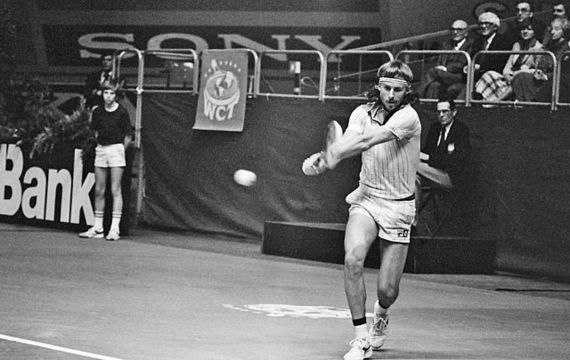

The term is borrowed from tennis and two great tennis players from Sweden come immediately to mind. Björn Borg and Mats Wilander won 18 Grand Slams between them, doing the damage mostly from the baseline. Net-rushers became victims to their precise, penetrating and counterpunching shots.

In chess, it was another Swede, Ulf Andersson, who loved to shuffle his pieces in his own backyard, unwilling to cross the middle of the board, only to lash out when least expected. He sharpened his baseline skills even with the white pieces.

In several chess defenses such as the Sicilian, the French, the Caro-Kann, the Pirc or the Modern, the black players are forced to stay within their back rows. But to do it voluntarily as white?

One of the first great players to sit back as white was the remarkable hypermodernist Richard Reti. In a limited space of the first three rows, Reti invented a marvelous setup. It didn't resemble a warehouse, it was an elegant, almost gallery-like display of his pieces. Sometimes it didn't quite work, but when it did, it was a pleasure to watch. Alexander Alekhine, writing notes in the tournament book New York 1924, was impressed by the following game.

Reti,Richard - Yates,Frederick

New York 1924

There is vigor in Reti's efficient treatment of his heavy pieces. He put them in one bag on the queenside: the rooks are placed on the open c-file and the battery of queen and bishop is aiming at the central pawn e5.

Suddenly, he moves his d-pawn to the fourth rank and the position bursts open in his favor.

17.d4!

"Clarifying the pawn position in the center at the right moment and thereby gaining either d4 oir e5 for his knight. From now on black's game deteriorates rapidly," writes Alekhine.

17...e4

"After 17...exd4 18.Nxd4 followed by doubling of the white rooks on the d-file, the game could not have been saved for any length of time," says Alekhine

18.Ne5!

Reti's first piece crosses the median with disastrous results for black.

18...Bxe5

Clearly forced.

19.dxe5 Nh7 20.f4

"The control of the black squares and the weakness of the hostile d-pawn are now decisive factors in favor of white. By the subsequent exchange, in conjunction with the tour of the knight to h3, the opponent, of course, makes victory easy." - Alekhine

The game concluded:

20...exf3 21.exf3 Ng5 22.f4 Nh3+ 23.Kh1 d4 24.Bxd4 Rad8 25.Rxc6! bxc6 26.Bxc6 Nf2+ 27.Kg2 Qxd4 28.Qxd4 Rxd4 29.Bxe8 Ne4 30.e6 Rd2+ 31.Kf3 Black resigned.

Bobby Fischer was one player you would not expect to stay back with the white pieces. In 1970 the American grandmaster experimented with the first move 1.b3 and defeated Vladimir Tukmakov, Miroslav Filip and Henrique Mecking. But it was his victory against Ulf Andersson that was the most impressive. It was played around the time of the 1970 Chess Olympiad in Siegen and it was sponsored by the Swedish newspaper Expressen.

Fischer,Robert James - Andersson,Ulf

Exhibition Game 1970

Fischer has a typical Hedgehog setup with the white pieces. But instead of seeking a counterplay in the center, he finds an amazing way of attacking the black king.

13.Kh1! Qd7 14.Rg1 Rad8 15.Ne4

Fischer starts his offensive by leaping out with the knight.

15...Qf7 16.g4!

Advancing the pawn secures important squares.

16...g6 17.Rg3 Bg7 [17...Nb6 18.g5!] 18.Rag1 Nb6 19.Nc5 Bc8 20.Nh4 Nd7 21.Ne4 Nf8 22.Nf5!

The white knights and rooks are fully engaged. Fischer won in 43 moves.

Bill Hook photographed Andersson in 1992

Andersson definitely learned something from the game, but advancing pawns in front of his king was not his style. Perhaps unknowingly, he tapped into the origin of the Hedgehog by placing the battery (Queen and bishop) on the diagonal b1-h7 in our game played in the Spanish town of Montilla.

Andersson, Ulf - Kavalek, Lubomir

Montilla 1974

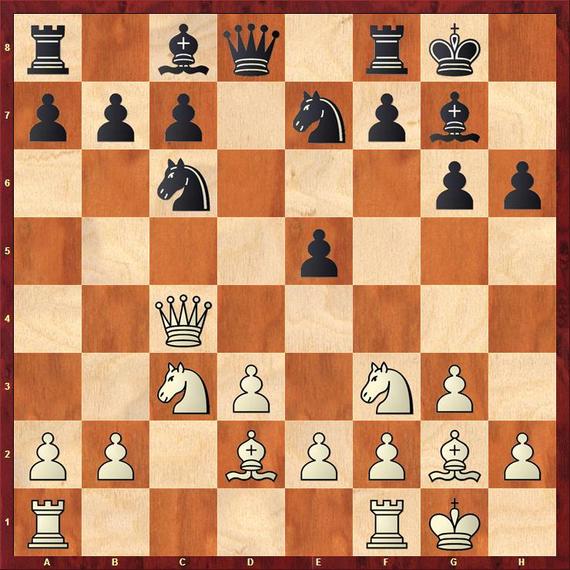

Andersson's pieces are posted on the first three rows, waiting for action. But Black has more space and no apparent weaknesses. The next five moves are also suggested by the computer program Houdini 4 Pro.

21.h4

I was not sure Andersson was happy about this move, weakening his kingside.

21...f5 22.Qa1 Nf6!? 23.b4

Diverting the attention from the center. Andersson was not particularly interested in 23.Nxe5 Nxe5 24.Bxe5 Rxe5 25.Qxe5 Ne4 26.Qf4 Nxd2 27.Rcd1 Bc3 28.Rxd2 Bxd2 29.Qe5+ Kg8 30.Rd1 Re7 31.Qf6 and now either 31...Bb4 32.axb4 cxb4 or 31...Bxe3 32.fxe3 Qd5 33.e4 Qd4+ 34.Qxd4 cxd4 with black's edge.

23...axb4 24.axb4 Nxb4 25.Nxe5 Nxc2 26.Rxc2

Black's position is more pleasant, but not by much.

26...Rde7 27.Nxg6+ hxg6 28.Bxf6 Qxd3 29.Rec1 Kh7= 30.Nf3?!

The faulty knight move swings the pendulum in black's favor. White should have played more aggressively: 30.Bxg7 Rxg7 31.Qf6 with equal chances.

30...Bxf3! 31.gxf3 f4!

The white king is in trouble and in addition black has two connected passed pawns on the queenside.

32.Bxg7 Rxg7 33.Rc3 Qd8 34.e4 (34.exf4!?) 34...g5 35.Kf1?

Losing. 35.hxg5! Qxg5+ 36.Kf1 was White's only chance to survive.

35...g4!

Breaking through, but 35...gxh4 36.Ke2 h3 also wins.

36.fxg4 Qxh4 37.f3 Rd8 38.Rd1 Rgd7

This is sufficient to win. But infiltrating to the second rank and using the skewer was better: 38...Qh1+ 39.Ke2 Qg2+ 40.Ke1 Rd2!-+ 41.Rxd2 Qg1+ wins; or immediately 38...Rd2!

39.Rxd7+ Rxd7 40.Rc1 White resigned at the same time.

After 40...Qh1+ 41.Ke2 (41.Kf2 Rd2#) 41...Qg2+ 42.Ke1 Qg1+ 43.Ke2 Qe3+ 44.Kf1 Qxf3+ 45.Kg1 Qxg4+ 46.Kf1 Qf3+ 47.Kg1 Rd6! 48.Qa7+ Kh6 and black mates.

The game was not well known and it didn't find its way into important databases such as the 2014 Mega by Chessbase or into Sergei Shipov's magnificent work on the Hedgehog.

Ljubomir Ljubojevic is credited with developing the Hedgehog in the modern era - in the early 1970s. Ljubo rarely missed a dynamic opportunity and the counterpunching Hedgehog was a perfect fit for him. He discussed the defense with Andersson and they became the Hedgehog brothers. The opening played a big part in their success. In 1983, they were rated just behind Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov: Ljubo was third and Andersson fourth on the FIDE rating list.

According to available sources, the Hedgehog was first played in Czechoslovakia by Fritz Sämisch against Karel Opocensky in a tournament in the Slovakian spa of Pieštany in 1922.

Opocensky, Karel - Sämisch, Fritz

Pieštany 1922.

We see the position with all the ingredients of the Hedgehog, the spiny black pawns on the sixth rank and the pieces hiding behind them. We also see the battery, queen and bishop, that Andersson employed with the white pieces 52 years later.

We know Sämisch influenced the opening theory with variations in the Nimzo and King's Indian defenses. His contribution to the Hedgehog was less obvious, hidden for years.

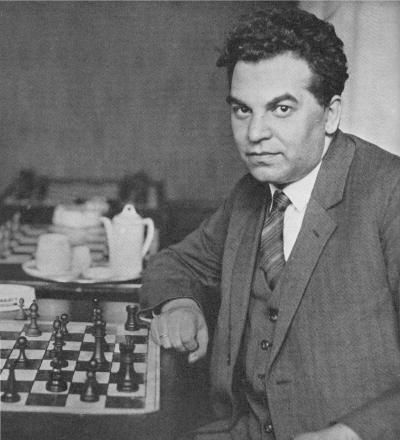

Salo Flohr, the all-time finest Czech player, used Sämisch's setup in the game against Karel Treybal in Ujpest in 1934.

Treybal, Karel - Flohr, Salo

Budapest 1934

In 1937, FIDE chose Flohr to be the official challenger for the world championship match against Alexander Alekhine. But the match never took place and in 1939 Flohr emigrated to Soviet Union where he had to compete with many talented players.

Flohr was an excellent chess journalist. We worked together in 1966, commenting on the world championship match between Boris Spassky and Tigran Petrosian for a Czech daily. I was in Prague, Flohr was in Moscow. I got all the gossip from him with many marvelous details, including the color of Petrosian's socks. Telephone was our connection. Today you can see Carlsen's socks on your smartphone.

Technology dominated the coverage of the match in Chennai. Internet reporting was massive: chess twitterati with analytical engines tried to outdo themselves like the old court wits, chess was also big on Facebook. And we should not forget the millions of television viewers. What a leap forward in the last 50 years!

I noticed that the match was getting personal during Game 3. After the first 10 moves, Carlsen reached the same position I had 40 years ago against Arthur Bisguier, although the move order was different. We both spread the white pieces on the first three rows, only our queen was floating around, waiting to be chased back any moment.

Anand, Viswanathan - Carlsen, Magnus

World Chamionship, Chennai 2013, Game 3

and

Kavalek, Lubomir - Bisguier, Arthur

U.S. Championship, El Paso 1973

Anand played 10...Nd4 11.Nxd4 exd4 12.Ne4 c6 13.Bb4 Be6 and equalized.

Bisguier attacked the queen immediately 10...Be6 and after 11.Qa4 Nd4 12.Rfc1 a5 13.Qd1 Re8 14.Ne1 c6 15.e3 Ndf5 16.a3 Nd6 I lost the battle for space. After some dramatic moments, the game was drawn in 59 moves.

Bisguier was one of the world's best experts on the Berlin defense (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 Nf6) already in the 1960s despite his famous loss to Bobby Fischer at the 1963 U.S. Championship. The Petroff defense (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nf6) was another opening he liked to play. When I could not get any advantage against him at the 1972 U.S. Championship in New York, I decided to improvise a year later with the reversed Pirc defense. To my surprise, Carlsen reached the same position. Time stood still for 40 years.

In the championship in El Paso in 1973 John Grefe played the tournament of his life, winning game after game. He had a marvelous run and was well prepared. He came up with many original and fascinating ideas. I was lucky to chase him down, and we shared the U.S. title. We thought that a new star was born, but John had other priorities. He returned to chess towards the end of his life. Sadly, he died on December 22 of last year at the age of 66.

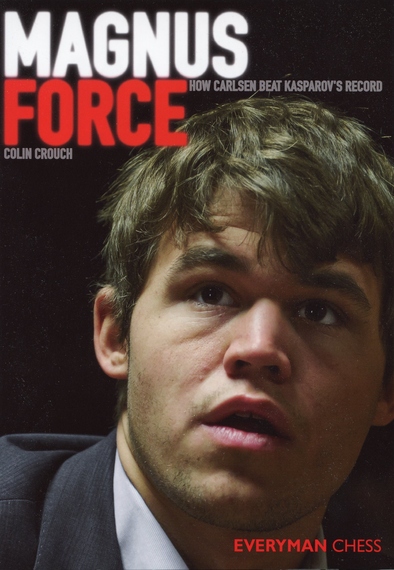

Given a choice, Carlsen would prefer to fight against the Hedgehog. He knows what to do with space as he demonstrated in Game 10 against Anand. Another example was his victory against Judit Polgar in London in 2012, published in this column. That game was also included in Colin Crouch's fascinating book Magnus Force, published by Everyman Chess.

It is a 420-page journey into Carlsen's brain. There are only 28 games covering the time Carlsen broke Kasparov's record, but it allows Crouch to write many little essays into the comments, ranging from general remarks to specific advice. As usual, Crouch is on top of his writing game.

Whether you agree or disagree with Crouch, he always gives you an honest opinion. "Carlsen, despite the occasional recent glitches, is quite clearly an excellent handler of chess psychology," he writes. But may be it is more simple. "I don't believe in psychology," said Bobby Fischer. "I believe in good moves." And that also seems to work for Carlsen.

There is no doubt, Carlsen was outplayed by Anand in Game 9, but he found a way to stay in the game. And he was able to prevail, having lined up all his pieces on the last row.

Anand, Viswanathan (2775) - Carlsen, Magnus (2870)

World Championship, Chennai 2013, Game 9

With his last move 26...b2 Carlsen serves a remainder that it is dangerous to lift pieces for the attack, but Anand does it anyway.

27.Rf4!?

It was possible to back-off with 27.Ne2 Qa5 28.Nf4 Be6 (28...Qa1? 29.Nxd5+-) 29.Nxe6 (29.Bh3 Bxh3 30.Qxh3 Qa1-+) 29...fxe6 30.Bh3 Qa6 31.Bg4 Rf7 32.Qh3 Nc7 33.Qg2 Qa1 34.Qc2 Rf8 35.f7+ Rxf7 36.Rb1 Rf4 37.h3 with equal chances.

After 27.Rb1 Qa5 the black queen cleans up white's queenside pawns since 28.Ne2 Qa2 wins easily.

27...b1Q+ 28.Nf1?

For a brief moment Anand thought that he was winning and was thrilled about the possibility. He overlooked Carlsen's reply. Interestingly, being a queen down, Anand is not losing.

He had to play 28.Bf1! and while black can defend with 28...Qd1! 29.Rh4 Qh5! 30.Nxh5 gxh5 31.Rxh5 Bf5 the break 32.g6! secures white drawing chances, for example 32...Bxg6 33.Rg5 White simply threatens to march his h-pawn. Black has a choice:

A. 33...Nxf6 34.exf6 Qxf6 35.Rxd5 Qf3 (or 35...Re8) 36.Rc5 Qxc3 37.Qf4 Rd8 38.Rxc4=

B. 33...Qa5 34.Rg3 Qa3 35.h4 Kh8 36.h5 Be4 37.Qg5 Qa6 (37...Bd3 38.e6!+-; 37...Qa1 38.e6! fxe6 39.f7+-) 38.Qh6 Rg8 39.Rxg8+ Kxg8 40.Qg5+ Kh8 41.Qh6 Qa3 42.Bh3 Qa1+ 43.Bf1 Qa3 the position is balanced. Black is a piece up, but he can't free himself from white's grip. On the other hand, white can't improve his position.

28...Qe1!

What a difference one square makes! Anand was excited, seeing he could win after 28...Qd1 29.Rh4 Qh5 30.Rxh5 gxh5 31.Ne3 Be6 32.Bxd5! threatening 33.Be4, and now: 32...Bxd5 33.Nf5 Be6 (33...Be4) 34.Ne7+ wins; or 32...Qxd5 33.Nxd5 Bxd5 34.h4 and white wins by moving his king to the square c5 where it can support the advance d4-d5. Black is tied up and can only move his bishop.

But Anand's joy was short-lived. He realized that after 28...Qe1! 29.Rh4 Qxh4 the game is over.

White resigned.

The game ends with five black pieces on the back rank. Only the newborn queen sees the action and decides the game. Carlsen won the game without moving his queen on d8 and the bishop on c8. A unique game, indeed! Can somebody do it with the white pieces?

Note that in the replay windows below you can click either on the arrows under the diagram or on the notation to follow the game.

Images by Bill Hook, Anastasiya Karlovich and Wikipedia