The winner had no name. The 1978 Women's Singles Wimbledon final was reported as "Chris Evert lost 2-6, 6-4, 7-5," but nobody was fooled by the censors back in Czechoslovakia. The whole nation knew that Martina Navratilova won her first Wimbledon title.

In 1975 at the U.S. Open, Navratilova asked for political asylum and became persona non grata at home. Her name disappeared from the press. It was a game the communist establishment liked to play. The censors axed your name and the people learned how to read between the lines.

I met with similar fate after I left Czechoslovakia in 1968. Chess tournaments in which I participated were not reported or appeared without my name. The same year Martina left, a book of chess puzzles by two Czech grandmasters, Vlastimil Hort and Vlastimil Jansa, was published in Prague. The publisher Olympia printed 18,000 copies and when it was done, some censors discovered my name attached to one of the games. They did something unbelievable: they cut out the page with my name, printed a new one without my name and glued it back in the book. They did it page by page, book by book --18,000 times.

They erased our names, but at least we lived. During the Great Terror of the late 1930s many people were executed by the Soviet secret police just because they said something wrong. Talented chess composers such as Sergei Kaminer, Arvid Kubbel, Mikhail Platov, Petr Moussoury and Mikhail Barulin lost their lives. After Stalin's death, they were posthumously rehabilitated, but it was too late.

Today's puzzles, published in their memory, were composed when the families were still together and the sacrifices were made only at the chessboard.

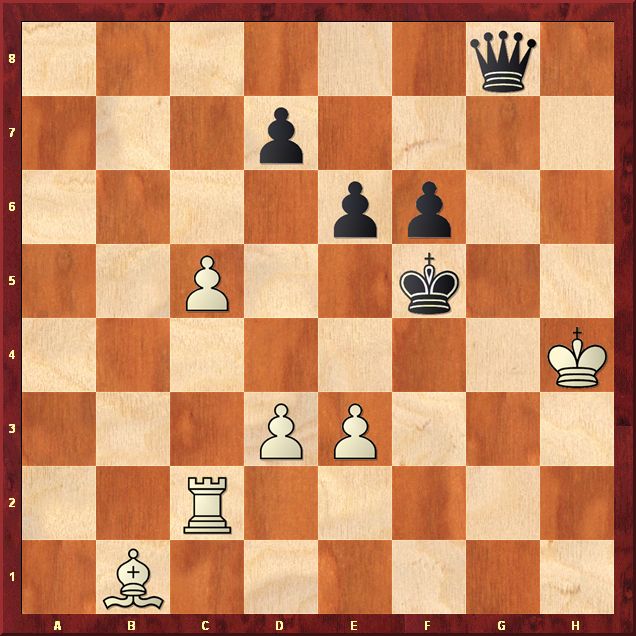

Arvid Kubbel (1889-1938), an older brother of the well-known composer Leonid Kubbel, was sent to Soviet gulag for sending his compositions to foreign "bourgeois" newspapers. He died a year later. Leonid published the following stunning work in Sovremenoye Slovo in 1917.

Leonid Kubbel

White wins

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

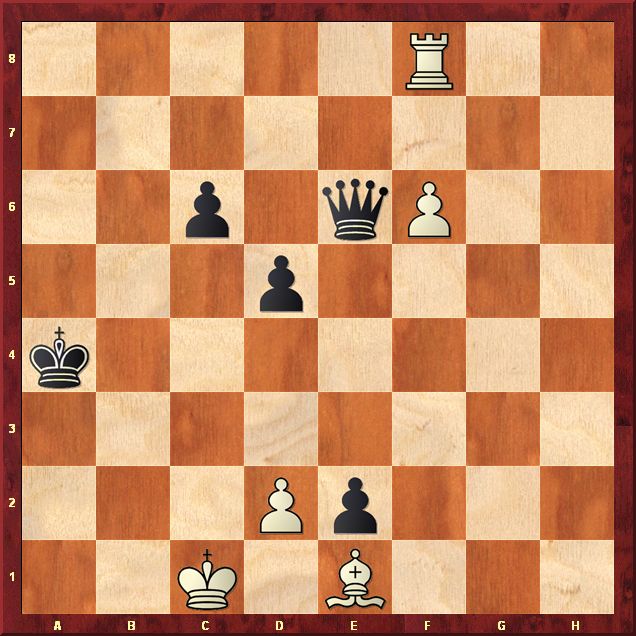

The Latvian-born Mikhail Platov (1883-1938) was the younger and lesser-known of the famous Platov brothers. He died in a forced labor camp, where he was sent for making a derogatory remark about Stalin. The brothers teamed up in a remarkable study, published in Sydsvenska Dagbladet Snallpost in 1911, in which some pieces disappear and others are born in a whirl of surprising moves.

Vassily and Mikhail Platovs

White wins

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

Shaw's show

Puzzle books are getting more and more sophisticated. In his recent Quality Chess Puzzle Book, the Scottish grandmaster John Shaw reveals that one of his favorite books is The Best Move by Hort and Jansa. This is the English version of the above-mentioned Czech book, published by RHM Press in 1980. Not only was my name reinstated but the book was translated by my wife. It became an instant classic and its format was used by other authors.

The Czech grandmasters presented their puzzles on the right-hand side. Turn the page and you find the solution. Simple and easy. They also rewarded the readers with points for correct solutions. Igor Khmelnitsky, another writer influenced by The Best Move, went even further in his successful books Chess Exam and You vs. Bobby Fischer, adding ratings to the points.

This is a hard thing to do, but Khmelnitsky was often accurate.

Shaw does not use any points and presents only well-explained solutions to the 735 puzzles. He points out that the book is a collective work of Quality Chess team with a lot of work done by Jacob Aagaard. The material is fresh and 700 puzzles are taken from games not older then 10 years. A special tribute is paid to Vassily Ivanchuk and one of the 15 chapters is devoted to his mastery. Each chapter is introduced by wonderful game-fragments relevant to the theme. Missed opportunities, puzzles with two solutions and defense strategies are not often found in puzzle books, but they flourish in Shaw's extensive work. It is a rare and original contribution, chartering new territory. I would recommend it to tournament players.