Botvinnik during his last tournament, Leiden 1970

Chess players around him had disappeared, having been executed or sent to gulags, but he lived. Mikhail Botvinnik (1911-1995) survived because he made himself indispensable. Even the architect of Soviet chess, Nikolai Krylenko, became a victim of Stalin's purges in the late 1930s having been accused of spending too much time climbing mountains and playing chess. His goal was to export chess as part of Soviet culture and to dominate the chess world. He did not live to see it happen. Botvinnik was the most important chess player of Krylenko's legacy.

In his new book Mikhail Botvinnik, The Life and Games of a World Chess Champion, published by McFarland, Andrew Soltis writes:

"[Botvinnik] was born under a monarchy, lived through a revolution, a civil war, the brutal collectivization and famine, the Terror, a second world war and a cold war, the end of Stalin and a "thaw", the malaise of the 1960s and 1970s, the Gorbachev reforms of glasnost and perestroika and, at the age of 80, the end of the Soviet Union and the beginning of an uncertain new Russia that is still trying to define itself."

Soltis tells a fascinating story of a man who seemed cold, unapproachable, and rather boring. Botvinnik was a devoted and convinced communist with ties to highest Soviet officials, including Stalin. He was the world champion for a span of 15 years and the leading Soviet player for more than 30 years. Generations of talented players, such as the world champions Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov and Vladimir Kramnik, learned from him how to play the game.

Botvinnik proposed playing rules to FIDE and defined the Soviet School of Chess. Its influence is still seen today: six of the eight participants in the Candidates tournament to establish the challenger to the world champion Magnus Carlsen, underway in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia, were born in the Soviet Union. In his youth, Vishy Anand visited the Tal Chess Club at the Soviet Cultural Center in Chennai, India. And Veselin Topalov, no doubt, studied Soviet sources.

But not everything was rosy in Moscow. Boris Spassky once compared the lives of Soviet grandmasters to the lives of spiders in a bottle.

Soltis says his book is an attempt to explain Botvinnik in the context of today. It is a brilliant account, the best book written on Botvinnik by far. Soltis did extensive research, using mainly Soviet sources. Both Botvinnik's friends and critics have a voice in the book.

The games are an important part of the book and Soltis uses mostly Botvinnik's notes. I have included some of them in my commentaries. Botvinnik's game against the Austrian attacker and the author of the classic The Art of Sacrifice in Chess Rudolf Spielmann, played in the first round of the 1935 Moscow tournament, is his most celebrated miniature victory, lasting only 12 moves.

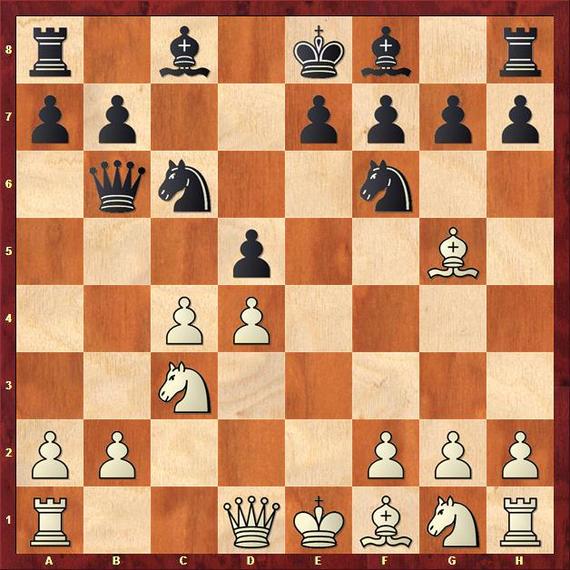

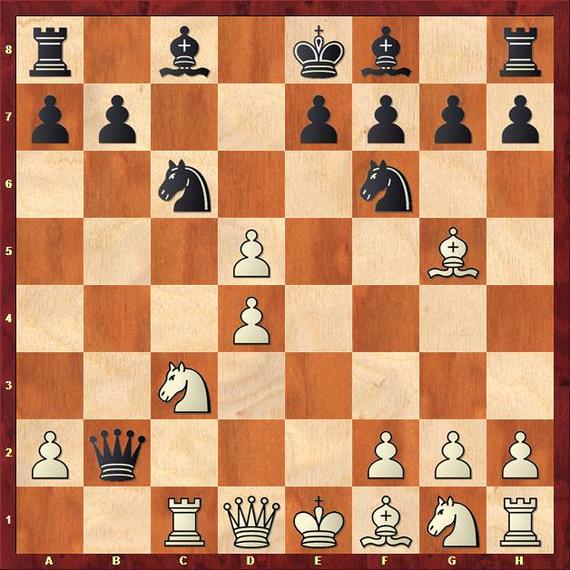

Botvinnik,Mikhail - Spielmann,Rudolf

Moscow 1935

1.c4 c6 2.e4 d5 3.exd5 cxd5 4.d4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 Qb6?!

This aggressive move was recommended by the Czech master Karel Opocensky in his chess column in Narodni politika after the 1933 match Botvinnik-Flohr and it was used for the first time by Josef Rejfir against Spielmann in Maribor 1934.

"Surprising and good," wrote Rejfir in Ceskoslovensky Sach 8-9/1934 about Opocensky's invention. The Wiener Schachzeitung called it the Prague variation.

7.cxd5!

According to Rejfir, after 7.Bxf6 comes 7...Qxb2 8.Nxd5 exf6! and because of the threat Bf8-b4+, white is unable to win the rook on a8. Today's computers confirm it: 9.Rb1 Qxa2 10.Nc7+? Kd8 11.Nxa8 Bb4+ 12.Rxb4 Nxb4 13.Be2 Bf5 and black wins back the knight on a8 with dividends.

Spielmann played the weak 7.c5?! Qxb2 8.Nge2 (8.Nb5? Ne4! 9.Be3 Nc3!) 8...Bf5! (8...Nxd4? 9.Rb1 Nc2+ 10.Kd2+-) 9.Qc1 'In a desperate situation white is trying to save himself by exchanging queens, because the threats Nc6-b4 or Nc6xd4 are deadly,' said Rejfir. 9...Qxc1+ 10.Rxc1 0-0-0 'Black is a pawn up and has beter chances," wrote Rejfir. "The threat is Nc6-b4. In order to move the knight on e2, white has to protect the pawn on d4." 11.Be3 Ng4 12.Ng3 Bg6 13.Be2 Nxe3 14.fxe3 e5! Black has to destroy white's central pawns. The pawn on d5 is not weak.

7...Qxb2?

Losing outright. Taking the d-pawn with the knight 7...Nxd4 was considered the only alternative.

7...Nxd4 8.Be3?! originally thought to be the refutation 8...e5 9.dxe6 Bc5 10.exf7+

A. 10...Kxf7! 11.Bc4+ Be6 with good chances to equalize.

B. 10...Ke7 the older move leading to white's advantage after 11.Bc4 Qxb2 (11...Bg4 12.Qxg4 Qxb2 13.Bxd4 Qxa1+ 14.Ke2 Nxg4 15.Nd5+ Kxf7 16.Bxa1) 12.Nge2 Nc2+ 13.Qxc2! Qxa1+ (13...Qxc2 14.Bxc5+ Kd7 15.Rd1++-) 14.Bc1 wins.

But white can improve after 7...Nxd4 with 8.Nf3! First played in the game Kavalek-Trapl, Vrbno pod Pradedem, 1959. Now 8...e5 can be simply met by 9.Nxe5 and after 8...Qxb2 9.Rc1 Nxf3+ 10.Qxf3 a6 (10...e5 11.Rb1) 11.Bd3 and white has a good compensation for the pawn.

8.Rc1!

Botvinnik's improvement on 8.Na4 Qb4+ 9.Bd2 Qxd4 10.dxc6 Ne4 11.Be3 Qb4+ 12.Ke2 bxc6! (12...Qxa4? 13.Qxa4 Nc3+ 14.Ke1 Nxa4 15.Bb5+-) 13.Rc1 Qb5+ 14.Ke1 (14.Kf3 Qh5+ 15.Kxe4 Bf5+ 16.Kd4 Rd8+-+) 14...Qa5+ 15.Nc3 Nxc3 16.Qd2 e5 17.Ne2 Bf5 18.Nxc3 (18.Rxc3 Rb8 19.Rb3 Bb4 20.Rxb4 Qxb4 21.Qxb4 Rxb4 22.Nc3=) 18...Ba3 with black's advantage.

8...Nb4

Other moves are also inadequate:

8...Na5 9.Qa4+;

8...Nb8 9.Na4 Qb4+ 10.Bd2 Qxd4 11.Rxc8++-;

8...Nd8 9.Bxf6 exf6 10.Bb5+ Bd7 (10...Ke7 11.Rc2 Qb4 12.Qe2+) 11.Rc2 Qb4 12.Qe2+ Be7 (12...Qe7 13.d6 Qe6 14.d5) 13.Bxd7+ Kxd7 14.Qg4+ Ke8 15.Qxg7 wins.

9.Na4 Qxa2 10.Bc4 Bg4 11.Nf3 Bxf3 12.gxf3

(After 12.gxf3 Qa3 13.Rc3 wins.) Black resigned.

There was a controversy in this tournament concerning the game Botvinnik needed to win to share first place with with Salo Flohr of Czechoslovakia. Soviet master Nikolai Ryumin, known for creating brilliant attacks, allegedly composed the 22-move mating combination for the game Botvinnik - Chekhover. These things are difficult to prove but Soltis shows that Botvinnik never really denied it outright. It remained a mystery as did his 4-1 score against the Estonian hero Paul Keres in the 1948 World championship tournament.

Soltis does not overburden the reader with long variations. His notes are guiding the games gracefully. Here and there he could have revealed more. For example, he does not mention a major discovery by the late Richard Cantwell, an American dentist and a strong chess amateur, who found a more precise continuation in Botvinnik's most famous encounter.

Botvinnik ,Mikhail - Capablanca,Jose Raul

AVRO Rotterdam 1938

29.Qe5?!

Cantwell wrote in the 2002 March issue of Chess Life that white wins with 29.Qc7+! a tactical maneuver to gain an important tempo after 29...Kg8 30.Qe5.

After 30...Kg7 white reaches the same position as in the game, but it is his move and he can continue 31.Ba3! (the bonus move) 31...Na5 32.Qc7+ Kg8 33.Be7! and black is in trouble, for example 33...Ng4 34.h3 Nc6 35.Bg5 h6 36.Bd2 Nf6 37.Bxh6 and white should win.

Whether Garry Kasparov read Cantwell's findings or not, he concurs that after 30...Qe7 31.Ba3 Qxa3 32.Qxf6 Qf8 33.Qe5 Qe7 34.Qxd5 b5 35.Ne4 white wins.

29...Qe7

Playing into Botvinnik's wonderful combination. In 1988, the Moscow master Vladimir Goldin suggested the defense 29...h6, controlling the square g5. When he informed Botvinnik about it, the former world champion played 30.Ba3, to which Goldin's 30...Qd8! prevents the queen invasion. White can still play for a win with 31.Qf4!, for example 31...b5 32.h4 a5 33.Ne2! (But not Goldin's 33.Qe5) 33...b4 34.cxb4 Qe7 35.bxa5 Qxa3? (35...Qxe6 36.Qc7+ Kg8 37.Qe5+-) 36.Qc7+ Kh8 37.Nf4 wins.

But after 29...h6, instead of 30.Ba3, Cantwell found that 30.Qd6! dominating the black queen, gives white excellent winning chances, for example

A. 30...Na5 31.Bc1! (threatening 32.Qc7+ and 33.Bxh6, winning) 31...Nc6 32.Qc7+ Ne7 33.Qxa7+-;

B. 30...a5 31.Ba3 b5 32.Qc7+ Kh8 33.Be7 Ng8 34.Qe5+ Kh7 35.Bd6 a4 (35...b4 36.Nh5) 36.Nh5!! gxh5 37.Qf5+ Qg6 38.Qf7+ and white wins.;

C. 30...Qf8 31.Qc7+ Kh8 (31...Kg8 32.Ba3) 32.Qe5 Kg7 33.h4 Na5 34.h5 Nc6 35.Qc7+ Ne7 36.Ba3 Nfg8 37.Qd7 and black is tied up.

30.Ba3!!

A wonderful deflection. The English grandmaster John Nunn calls it one of the most famous combinations of all time. During the 1954 chess olympiad in Amsterdam the celebrated position made it on an enormous cake displayed in the window of a local bakery. Botvinnik tells a story how the Russian computer "Pioneer" analyzed this position in 1979. To Botvinnik's disappointment it first suggested 30.Nf5, but later it found 30.Ba3!!

30...Qxa3 31.Nh5+!

Before Botvinnik could play this move, one of the spectators in Rotterdam shouted it out loud. The knight sacrifice is the key to Botvinnik's combination allowing the white queen to help promote the e-pawn.

31...gxh5 32.Qg5+ Kf8 33.Qxf6+ Kg8 34.e7

Kasparov gives another win: 34.Qf7+ Kh8 35.g3! and the white king hides on h3.

34...Qc1+ 35.Kf2 Qc2+ 36.Kg3 Qd3+ 37.Kh4 Qe4+ 38.Kxh5 Qe2+

Botvinnik shows 38...Qg6+ 39.Qxg6+ hxg6+ 40.Kxg6 and 41.e8Q mate.

39.Kh4 Qe4+ 40.g4 Qe1+ 41.Kh5 Black resigned.

Botvinnik and other world champions

From the eight world champions I played in my career, I drew all games against Botvinnik, Tigran Petrosian and Bobby Fischer. I was undefeated against Vassily Smyslov, beating him twice. I lost one game to Mikhail Tal and Garry Kasparov.

I won once against Anatoly Karpov, but lost four times with plenty of draws. My worst score was against Boris Spassky: in 21 games I lost six times and won twice.

Some of the draws against the world champions were dramatic and had a powerful theoretical impact. For example, my game with Fischer "determined for a long time the main trend in one of the sharpest lines of the Najdorf Variation in the Sicilian defense," according to Kasparov.

Still, it puzzled me why my drawn game against the Soviet patriarch was included in his collection "Botvinnik's Best Games 1947-1970." At the 1972 Chess Olympiad in Skopje, I was able to find out. I was playing the first board on the U.S. team, Botvinnik was there as an honorary guest.

"The game showed that my calculating power was not what it used to be," was his answer, and he added unexpectedly: "My playing strength was declining." Botvinnik always thought about his chess objectively.

The see-saw battle was described in the daily tournament bulletin as chaotic after it took a sharp turn around move 15. The spectators and journalists were united in preferring the side of the former world champion, but they got lost in calculations. For every suggested win, there was some defense or escape. The Belgian GM Alberic O'Kelly found only one clear-cut win after analyzing it for two weeks. Suddenly, I threw my heavy pieces toward Botvinnik's king, leaving my monarch unprotected. The game had become tense and slippery. On move 37 Botvinnik had a choice of three moves: one would lose, one would win, and he picked up the drawing alternative. The tournament bulletin gave this advice: Highly recommended for further study! "Botvinnik missed an opportunity to win what would have been one of his finest games," Soltis concluded.

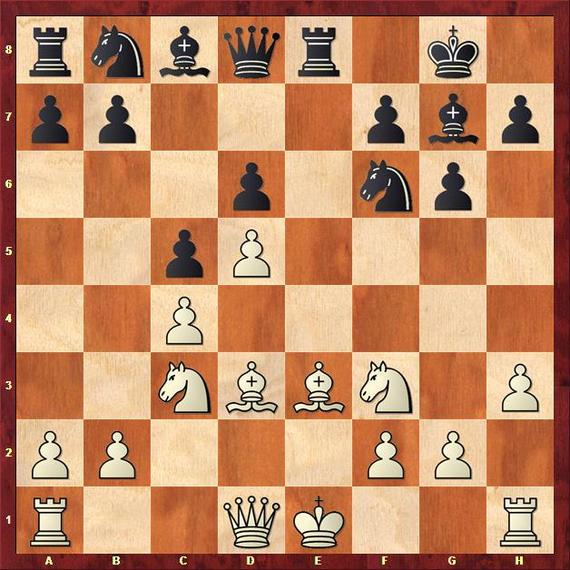

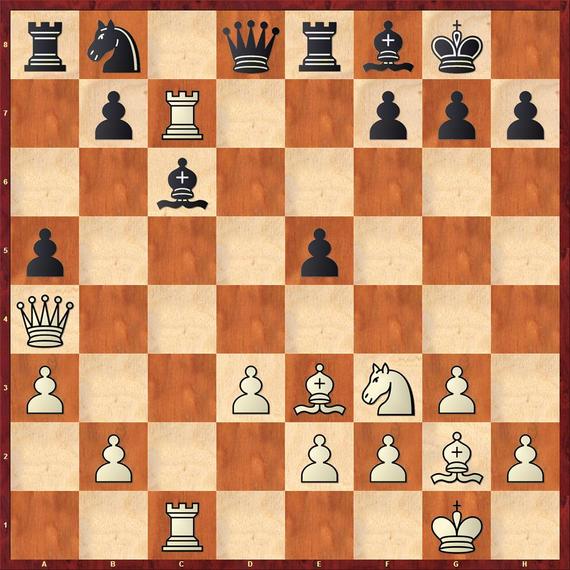

Botvinnik,Mikhail - Kavalek,Lubomir

Wijk aan Zee 1969

1.c4 g6 2.d4 Bg7 3.Nc3 c5 4.d5 d6 5.e4 Nf6 6.Bd3 0-0 7.h3 e6 8.Nf3 exd5 9.exd5!?

Designed to extinguish any spark of counterplay, this Ben-Oni variation also makes it difficult for black to develop. His light pieces may trip over each other, lacking space. It is a safe choice, avoiding complications after 9.cxd5 b5, but I thought it had a drawback.

9...Re8+ 10.Be3

Botvinnik's key move, not being afraid to go into the pin and sacrifice a pawn. I knew he played it against Milan Matulovic at Palma de Mallorca in 1967, but I thought I could challenge it successfully with my next move. I didn't know how thoroughly he had analyzed it. After 45 years there is no final verdict on Botvinnik's idea.

10...Bh6?!

Exchanging the dark bishops can help black to close the e-file, get some play on the dark squares and avoid massive exchanges of the heavy pieces. It is not easy to coordinate this strategy since white can shift the pressure to the f-file.

Fifteen years after this game, the exchange sacrifice 10...Rxe3+!? appeared, stressing that the dark bishop could be more effective than the rook, dominating the dark diagonals and lurking in white's camp. It was refined last year by the Moscow wizard Alexander Morozevich this way: 11.fxe3 Qe7 12.e4 Nbd7 13.0-0 Nh5, with the idea 14...Nd7-e5.

11.0-0! Bxe3 12.fxe3 Qe7

Accepting the e-pawn 12...Rxe3 is a suicide. After 13.Qd2 all white pieces are ready to pounce while black's queenside is still in deep freeze.

13.e4 Nbd7 14.Qd2 a6

Preventing any future knight leap to the square b5.

15.Rf2 Ne5?!

I thought the pawn sacrifice gave me good play on the dark squares. It was the only way to establish the square e5 for the knight, but it was a gamble. It was also messy and I liked that. But I miscalculated.

"A serious mistake," said Botvinnik. "Black follows through logically with his plan, but gets a lost position. He had to play 15...Rf8 16.Raf1 Ne8 followed by f7-f6 with a solid, but passive position."

Perhaps, but Botvinik was very good when he had you on your knees. He knew how to increase pressure and improve his position.

16.Nxe5 Qxe5 17.Raf1 Nd7 18.Rxf7

It was not very pleasant to see Botvinnik's rook on the square f7. After all, Rxf7 was his coup de grâce in his brilliant victory against Lajos Portisch in Monte Carlo in 1968.

Botvinnik,Mikhail - Portisch,Lajos

Monte Carlo 1968

Portisch tried to win the exchange, but Botvinnik shocked him with one of his finest combinations - an incredible double-rook sacrifice.

17.R1xc6! bxc6 18.Rxf7!!

This position crossed my mind during my game with Botvinnik.

18...h6

Basically, surrendering the game to white's attack on the light squares. Accepting the rook leads to a beautiful mating attack. 18...Kxf7 19.Qc4+ Kg6 (19...Qd5 20.Ng5++-; 19...Ke7 20.Bg5++-) 20.Qg4+ Kf7 21.Ng5+ Kg8 22.Qc4+ Kh8 23.Nf7+ Kg8 24.Nh6+ Kh8 25.Qg8 mate.

The game continued: 19.Rb7 Qc8 20.Qc4+ Kh8 (20...Qe6 21.Nxe5+-) 21.Nh4! Qxb7 (21...Qe6 22.Qe4!+-) 22.Ng6+ Kh7 23.Be4 Bd6 24.Nxe5+ g6 25.Bxg6+ Kg7 26.Bxh6+ (After 26.Bxh6+ Kxh6 27.Qh4+ Kg7 28.Qh7+ Kf8 29.Qxb7 wins.) Portisch resigned.

18...Qd4+ 19.Kh1!

19.R7f2?! Ne5 20.Rd1?! Bxh3! is in black's favor, 21.gxh3?? Nf3+ wins.

19...Ne5

My queen and knight are ideally placed. But I realized I was forcing Botvinnik to make good moves without giving him any choice to go wrong.

20.Qf4!

Threatening to finish black with 21.Rf8+.

20...Bxh3!

Hanging by a thread. "Kavalek overlooked that after 20...Bf5 21.Rxb7 Nxd3 (21...Bc8 22.Re7!+-; 21...Qxd3 22.exf5 Qxf5 23.Ne4+-) 22.Qh6 white wins," Botvinnik explained.

21.Be2!

"Material balance has been re-established, but White has a decisive attack," Botvinnik wrote.

After 21.Qf6 Nxf7 22.Qxf7+ Kh8 23.gxh3 Qxd3 24.Qf6+ white has only a perpetual check. Black is fine after 21.gxh3 Qxd3.

21...Bd7

After 21...Bxg2+ 22.Kxg2 Nxf7 23.Qxf7+ Kh8 24.Qf6+ Qxf6 25.Rxf6 Rad8 26.Rf7 white is in charge.

22.Qf6?

After 20 minutes of thinking, Botvinnik did not play the best move. He intended 22.Rf6! but thought that after 22...Kg7 23.Rd1?! Rf8! 24.Rxd4 Rxf6 black has some chances of resisting.

He also looked at 22.Rf6! Kg7 23.Rxd6 Rf8 but didn't see 24.Rf6! and white wins, for example 24...Nd3 25.Rf7+!

22...Nxf7 23.Qxf7+ Kh8 24.Qxd7 Rf8 25.Qxd6

"As Kavalek correctly stated after the game, after 25.Rf7 Rxf7 26.Qxf7 black is forced to enter an endgame with 26... 26...Qg7 ," Botvinnik revealed. The point is that white can quickly create a passed pawn with 27.Qxg7+ Kxg7 28.e5! dxe5 29.Na4 and should win.

25...Rxf1+ 26.Bxf1 Qf2 27.Qe5+ Kg8 28.Qe6+ Kh8 29.Qe5+ Kg8 30.Qe6+

The famous Soviet move-repetition, no matter how practical it may be, it always spoils beautiful games.

30...Kh8 31.Be2 Rf8

A critical position.

32.Qe5+?!

The Belgian count Alberic O'Kelly de Galway, my teammate on the powerful Solingen team, suggested the winning move 32.d6!

It not only brings the d-pawn closer to promotion, but it also opens the square d5 for the knight or the queen, whichever piece is needed there.

For example:

A) 32...Qh4+ 33.Qh3 Qe1+ (33...Qg5 34.Nd5!+-) 34.Kh2 Rf4 35.d7 wins.

B) 32...h5 33.Nd5! Qxe2 34.Qe5+ Kg8 35.Nf6+ Rxf6 36.Qxf6 wins.

C) 32...Rf4 33.Bg4 Qh4+ 34.Bh3 Rf1+ 35.Kh2 Qf4+ (35...Qe1? 36.Qe5+ Kg8 37.Be6+ Kf8 38.Qh8 mate. The pawn on d6 helps to close the mating net.) 36.g3 Qf2+ (36...Rf2+ 37.Bg2+-) 37.Bg2 Qg1+ 38.Kh3 Rf2 and now white can protect against all threats with the following maneuver: 39.Qe5+ Kg8 40.Qd5+ Kg7 41.e5 Qc1 42.Qxb7+ Rf7 43.Qe4 winning.

32...Kg8 33.Bg4 Qh4+

An obvious check, but I could have freed my king with 33...h5!? 34.Be6+ (34.Bh3 Qe1+ 35.Kh2 Rf1-+) 34...Kh7 35.Kh2! Qd2! 36.d6 Rf2 37.Nd5!? (37.Qg3 Rf1 and the threat 38...Qc1 is unpleasant.) 37...Rxg2+ 38.Kh3 and now:

A) 38...Rf2! 39.Qg3 Qe1! 40.Bg8+! Kxg8 (40...Kg7 41.Qc3++-) 41.Qxg6+ Kf8 42.Qh6+ Kf7 43.Qh7+ (43.Qxh5+ Kg7 44.Qe5+ Kh7=) 43...Kf8 44.Qe7+ Kg8 45.Nf6+ Rxf6 46.Qxf6 Qxe4 and black has good drawing chances.

B) 38...Rg1? 39.Bg8+! Kxg8 (39...Kh6? 40.Qf4+!) 40.Nf6+ Kg7 41.Qe7+ Kh6 42.Ng8 mate.

34.Bh3 Qe1+ 35.Kh2 Rf1!

Threatening 26...Rh1 mate. Botvinnik didn't believe I could send the rook down, leaving my king unprotected. 'The black king astonishingly slips out of the ambush,' he said.

36.Be6+ Kf8

All three results were possible at this point. To win the game, Botvinnik had to march up with his king - a very dangerous proposition in time trouble, not being able to fully calculate the consequences. He plays it safe and checks, and that leads only to a draw. With a different check, he could even lose.

37.Qh8+?

Botvinnik's final mistake, but it is hard to blame him. He didn't have much time to think. And he could have made a fatal error. When the game finished Pal Benko pointed out that after 37.Qd6+? Kg7 38.Qe7+ Kh8 white has to give a perpetual check. Benko dismissed 38...Kh6! because he thought that 39.Kh3 should win, overlooking 39...g5 and black wins.

The queen checks don't do the job: 37.Qh8+ only draws and 37.Qd6+ even loses. What else is there?

Astonishingly, a quiet king-move 37.Kh3! is the only winning try, but difficult to make when you are running out of time. It is not for the faint of heart. Botvinnik didn't even considered it in his analysis afterwards. The white king walks into a carousel of checks, but escapes the danger and white should win.

For example:

A. 37...Qe3+ 38.g3 Rh1+ 39.Kg2

A1. 39...Qg1+ 40.Kf3 Qf1+ 41.Ke3 Qc1+ 42.Kd3 Qf1+ 43.Kc2 Rh2+ 44.Kb3 Qf2 45.Qh8+ Ke7 46.Qg7+ Ke8 47.Ka4! b6 (47...Qc2+ 48.Ka5!) 48.Ne2! and black gets mated. But not 48.d6?? Qc2+ 49.b3 Qxa2+! 50.Nxa2 Rxa2 mate.

A2. 39...Rg1+ 40.Kh2 Qf2+ 41.Kh3 Qg2+ 42.Kg4 Rf1 43.Qh8+ Ke7 44.d6+! Kxe6 45.Qe8+ Kxd6 46.e5+ Kc7 47.Nd5+ wins.

B. 37...Rh1+ 38.Kg4 Qh4+ (38...Rh4+ 39.Kf3 Qf1+ 40.Ke3 wins.) 39.Kf3 Rf1+ 40.Ke3 Qf2+ 41.Kd3 Qxg2 (41...Re1 42.Qh8+ Ke7 43.Qxh7+ Kf8 44.Qh8+ Ke7 45.Qg7+ Ke8 46.Qxg6+ Kd8 47.Qg8+ Kc7 48.Qc8+ Kb6 49.Na4+ wins.) 42.Qh8+ Ke7 43.Qxh7+ Kf8 44.Qg8+ Ke7 45.Qg7+ Ke8 46.Qd7+ Kf8 47.Bg4 the bishop comes back to help defend the white king and the game is over.

37...Ke7 38.Qxh7+ Kf6 39.Qh8+ Kg5 40.Qe5+ Kh6 41.Qh8+

It is now too late for the king to walk to victory. After 41.Kh3 Rh1+ 42.Kg4 Qh4+ 43.Kf3 Rf1+ 44.Ke3 Qf2+ 45.Kd3 black simply plays 45...Qxg2! and white is forced to give a perpetual check with 46.Qh8+ since he can't bring his bishop back to g4 anymore to protect his king.

41...Kg5 42.Qd8+ Kh5 43.Qh8+ Draw agreed.

Botvinnik was supposed to play Bobby Fischer in Leiden in 1970 and prepared for that match with Spassky. But the match collapsed and the Dutch organizers changed it to a four-player tournament. It was Botvinnik's last.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click either on the arrows under the diagram or on the notation to follow the game.

Images from Botvinnik's last tournament in Leiden in 1970 by Lubomir Kavalek