Baalbaki resigned. Baalbaki didn't resign.

"Baalbaki Forever" headlined the Maharat News website, saying that no sooner had the Lebanese Press Syndicate's head stepped down and media sighed with relief, than the nonagenarian who has reigned over one of the country's two journalism bodies for more than 30 years withdrew his resignation and dug in his heels.

Screen Shot of "Baalbki Forever" Headline

Had it materialized, the resignation would have been unprecedented in the history of the two print media syndicates.

One represents owners/publishers, the other editors/reporters.

Word of Mohamad Baalbaki's resignation gave journalists hope the organization could be overhauled to better reflect the profession's needs in today's newspaper world.

The "almost" resignation of Baalbaki and his union's council, or board, was the talk of the town this week and the source of ridicule by countless journalists who consider the man and his organization anachronisms in the 21st century.

Baalbaki has been re-elected eight times to his post, thereby excluding other potentially qualified candidates from representing the profession.

According to Rasha Al Atrash, a former newspaper reporter and editor who is managing editor of Al Modon E-Newspaper, "Baalbaki's resignation is simply a farce because the fact that he's been head of the syndicate for decades tells us a lot about the dynamics of internal elections."

The message this sends is that the syndicate is a mini dictatorship, a privileged club, akin to Arab regimes that popular revolutions are trying to topple, she said.

"How can we expect reforms from those who need to be reformed?" she asked rhetorically.

On October 2, Al Modon published an article entitled "Baalbaki Remains and the Syndicate is Mummified."

An infusion of new blood has been postponed until the end of 2014, it reported.

The issue of reform has haunted both syndicates for as long as anyone can remember.

Journalists complain that membership in either syndicate is reserved for their presidents' cheerleaders, namely supporters who ensure their re-election.

Baalbaki, who presides over the council representing both bodies, has long maintained candidates can always apply and that the committee in question would review their requests.

But insiders familiar with his thinking say he has repeatedly held up the convening of that committee when detractors criticized him.

The Lebanese daily Al Akhbar reported last month Baalbaki had resigned for health reasons but that council members tried to stem any leak to the media until a suitable announcement could be formulated and an acceptable replacement found.

The Press Syndicate and Journalists Union structures must comply with Lebanon's print media law that dates back to 1962 and that reform-minded legislators, activists and civil society groups have been trying to change for years.

The heads of the two bodies are "elected" along sectarian lines. The former is a Muslim, the latter a Christian.

"The Press Syndicate, which represents the owners of print licenses, must undergo serious modernization," said Ayman Mhanna, executive director of the Samir Kassir Foundation, named for assassinated Lebanese journalist Samir Kassir. "It must accept the emergence of new news actors, the liberalization of market access, and provide unwavering support to media organizations and journalists facing repression of their freedom of expression and right to information."

Mohammad Baalbaki (Rodriguez)

Mhanna described Baalbaki as a key figure of the Lebanese press corps who has stood by the families of assassinated journalists.

But good intentions are not enough, he said.

"Moreover, it (the syndicate) must undergo a complete institutional overhaul so it stops being associated with individuals," Mhanna insisted. "Otherwise it will remain a relic of the past, losing by the minute whatever legitimacy it has."

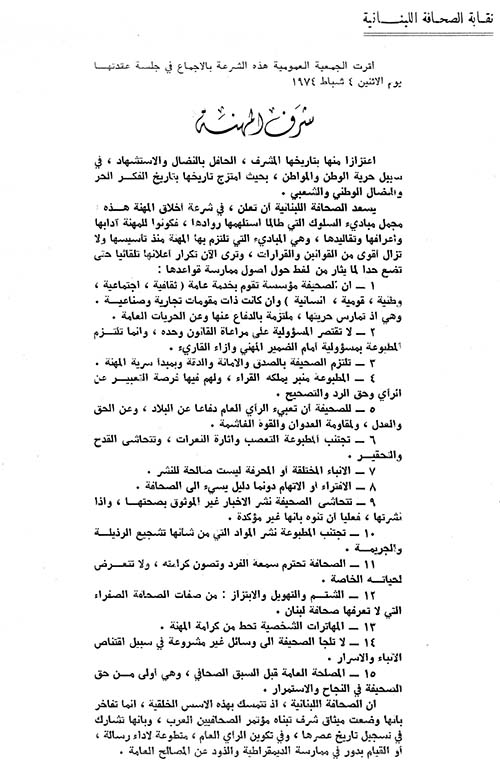

Even the syndicate's code of ethics is a throwback to days gone by. It emerged in 1974 and hasn't been touched since.

Lebanese Press Syndicate Code of Ethics (Abu-Fadil)

When I pointed out to Baalbaki at the turn of this century that it should be updated to keep up with the times and changes in technology, he retorted: "We like it this way."

One of several prickly pears has been the very definition of a journalist and whether online media can/should be included in the fold.

Draft legislation that is languishing in parliament would subject online arms of legacy print media to laws regulating newspapers. But personal blogs would be exempt from those rules.

"Unions and syndicates should represent professionals who actually practice, in that case every Lebanese journalist, including steady freelancers and broadcast journalists," said Al Atrash.

She feels the syndicate should defend journalists' rights, as opposed to siding with employers and the government - a charge echoed by others in the profession.

"How should the syndicate be run? Simply, democratically and in the most transparent way. It's not like trying to reinvent the wheel," she said.