"On résiste à l'invasion des armées; on ne résiste pas à l'invasion des idées" -- Victor Hugo.

Loosely translated: "One may be able to resist the invasion of armies, but not the invasion of ideas."

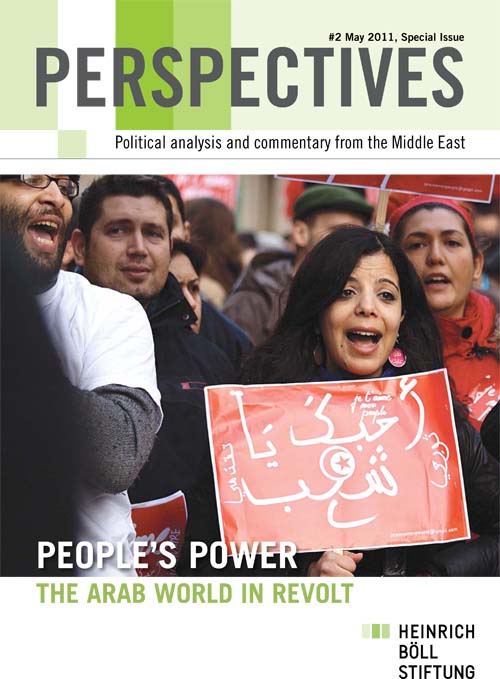

Cover of Perspectives Middle East (Courtesy HBF)

French author Victor Hugo must have been gazing through a crystal ball when he wrote these words some three centuries ago because they resonate true in 2011 with the outbreak of popular revolutions across the Arab world, egged on, in great measure, by traditional and social media.

Any invasion of armies today is being met with an equally hard-hitting invasion of media to cover unfolding events -- often to the consternation of those who seek to suppress people, invade countries, change borders, or just defend their own territories.

A common thread running through the revolutionary wave sweeping the region has been the fast dissemination of information, notably via Arab satellite channels like the Qatar-based Al Jazeera and Dubai-based Al Arabiya that are viewed in the remotest areas of most Arab countries.

Other local, regional and international channels broadcasting in Arabic have jumped on the bandwagon in a bid to capture Arab audiences, but Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya hold sizable pan-Arab viewership, with the former claiming to reach the largest number of viewers.

As such, their news coverage of unfolding revolutions has been instrumental in providing Arab audiences with information frequently hidden by their respective regimes on state-run media.

The use of dramatic footage, repetitive provocative graphics and titles to special segments on the unrest in whichever country was being covered, as well as charged background music befitting the revolt, have invariably contributed to the unsettled mood.

Cameras zooming in on demonstrators' catchy signs, or constant replays of citizen journalists' video footage from mobile devices of bloody scenes, panicked citizens, street violence, and general chaos, added to the dynamic of television with a combination of moving and still pictures.

How far are the media extensions of political interests?

To answer this question, it is worth considering journalist Fadia Fahed's take, entitled "Arab Media and the Lesson of the Street," in the pan-Arab daily Al Hayat.

"Arab media, long noted for their coverage of wars, news of death in Palestine, Lebanon, Afghanistan and Iraq, and their specialization in disseminating official pronouncements from their sources, are unaccustomed to covering popular movements and transmitting the voice of the street and their sons' daily tribulations," she said.

She was on target.

Official Arab media's raison d'étre is focused on personality cults of the respective Arab leaders and their cronies. Running afoul of these leaders usually means trouble, or worse.

"Arab media may have to change the meaning of journalism, give up fashionable ties and shiny shoes, go down to the street and convey the people's simple and painful concerns, with absolute loyalty to simple facts, and to return to their basic role as a mirror of the people, not the rulers," Fahed argued.

She added that the lesson came from the street.

As revolutionary fever grips the Middle East/North Africa region, more regimes are turning to knee-jerk extreme measures of clamping down on social media and access to the Internet, as well as controlling traditional news outlets.

But there are ways of circumventing governments' efforts to silence bloggers, tweeters, journalists and civil society activists. The more regimes tighten the noose, the more creative dissidents become in trying to loosen it.

According to the Menassat's Arab Media Community blog, "Avaaz is working urgently to 'blackout-proof' the protests -- with secure satellite modems and phones, tiny video cameras, and portable radio transmitters, plus expert support teams on the ground -- to enable activists to broadcast live video feeds even during Internet and phone blackouts and ensure the oxygen of international attention fuels their courageous movements for change."

And that is just one avenue. Countless others exist.

Peter Beaumont of Britain's Guardian newspaper wrote that social media have unavoidably played a role in recent Arab world revolts, with the defining image being a young man or woman with a smartphone recording events on the street, not just news about the toppling of dictators.

"Precisely how we communicate in these moments of historic crisis and transformation is important," he argued. "The medium that carries the message shapes and defines as well as the message itself."

The flexibility and instantaneous nature of how social media communicate self-broadcast ideas, unfettered by print or broadcast deadlines, partly explains the speed at which these revolutions have unraveled, and their almost viral spread across the region, he said.

"It explains, too, the often loose and non-hierarchical organization of the protest movements unconsciously modeled on the networks of the web," he added.

But lawyer/journalist/media consultant Jeff Ghannam countered that in the Middle East, this was not a Facebook revolution, and said one should not confuse tools with motivations.

Social media, he explained, helped make people's grievances all the more urgent and difficult to ignore.

It is that viral spread and non-hierarchical organization that inspired a Chinese activist who tweets under the handle "leciel95" to translate everything he could about events in Egypt to English and Chinese after Chinese authorities barred their media from reporting on the Egyptian revolution, according to Mona Kareem, who encountered him on Twitter.

Media coverage in times of conflict should not be judged in the heat of battle.

Far too many elements come into play when journalists are under tremendous pressure of deadlines, competition, financial considerations, and, very importantly, their own safety or existence.

It is unavoidable for reporters to feel pulled in one direction or another. They're only human.

It brings to mind the ethical question: Do you continue covering, shooting footage or taking pictures when bombs drop and people are being cut to shreds, or do you stop and help out? Can you do both? And, can you maintain your balance and sanity after that?

This is a summary of an article the author wrote for a special edition of Perspectives Middle East entitled "People's Power -- The Arab World in Revolt" published by the Berlin-based Heinrich Boell Foundation. It is available for download.