We've been hearing a lot about the US Constitution on both sides of the political divide or, to put it slightly differently, we've been hearing about the "constitutionality" of certain bills and laws proposed, passed or "pushed through."

Standing in Philadelphia, it is easier to remember that fidgeting with the Constitution and parsing its meaning is nothing new.

It was here, in 1787, that 55 men convened for four hot months, embroiled in bitter debate, to hammer out the document that begins with "We The People." It is, according to economist/actor/writer, Ben Stein, "the oldest governing document used in the world today, and based on eternal truths about man and government."

The National Constitution Center faces Independence Hall, where both the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution were signed.

Entering into a vast, somewhat drab lobby, you might think there's not much here, but most of the action takes place on the second floor, to which you ascend after an absorbing live and multi-media presentation called "Freedom Rising." Stadium-style seating rings a spot lit stage where a live actor begins, "We the people." You may get goose bumps as he/she goes on to explain that our county's quest for independence was "a step civilization had never taken before; this idea of a people deliberately willing to rule themselves." And then the part that not many of us remember from high school US History class; bound by the Articles of Confederation, our fledgling country's first guiding document, "within a few years, democracy started to stumble. Thirteen states each had their own army and currency. States argued over land rights."

Our central government was so weak it was practically non-existent. Rather than a "Perfect Union," we were just a "league of states.'"

In May 1787, a group of passionate, involved delegates were called to Philadelphia for a "constitutional convention," to tackle the issue of states rights versus federal power. Debating, disputing and hashing it out, often at loggerheads, for 114 long days, these fifty five men settled on a balance of power between three branches of government; Executive, Legislative and Judicial, giving each authority but not complete control. It was a form of government never before seen on this earth.

Interestingly enough, the rights we now take for granted were not included in the original US Constitution. (Nor was any mention of God, in the original document or in any subsequent amendment). Anti-Federalists were worried that the Constitution trampled on individual freedoms, and petitioned for a slew of modifications. That Bill of Rights (the first ten Amendments) as it was called, added in 1791, included our right to bear arms, to freedom of speech, to religious freedom, trial by jury, due process and others.

It took nearly another 80 years until slavery was abolished (13th Amendment) and Black Americans could officially be considered citizens (14th Amendment). In 1870, Black men finally got the right to vote (15th Amendment), but it would take another fifty years until women earned the same right, in 1920 (19th Amendment).

And in one instance, the government changed its mind; The 18th Amendment, which prohibited the manufacture, sale and distribution of alcohol (otherwise known as Prohibition), was repealed thirteen yeas later with the 21st Amendment.

The point is that interpretation of the US Constitution -- We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America -- is ongoing and has always been thus.

Sure, there are some on both ends of the political spectrum who feel that the most recent presidents have tested Constitutional limits, but are they the only ones to do so? Hardly.

In 1912, the Bull-Moose-tough Theodore Roosevelt pushed for "General Welfare" reforms while on the campaign trail -- managing to speak to a crowd with a bullet in his chest following an assassination attempt. ("It will take more than that to kill a Bull Moose!"). As President, Teddy brought 44 lawsuits against Big Trusts, convinced Congress to create the Department of Commerce and Labor, stewarded Child Labor and workplace Laws, and created the National Park system.

In 1933, distant cousin Franklin D. Roosevelt established his New Deal, steering fifteen new measures through Congress to end the banking crisis, aid farmers, regulate crops and create new government agencies in order to employ one million workers.

Naturally, these new proposals and measures elicited arguments and counter-arguments, which is, of course, the hallmark of a free society.

The history of our constitution is told in a great, interactive timeline on the second floor of the museum. Gauge your knowledge about US history though a Jeopardy-like computer game, watch Ben Stein answer letters about Constitutional facts and history on a looping video, come up with your own six-word critique or comment about our government which will be added to a growing database. (Mine was Democrats, Republicans; learn to work together!).

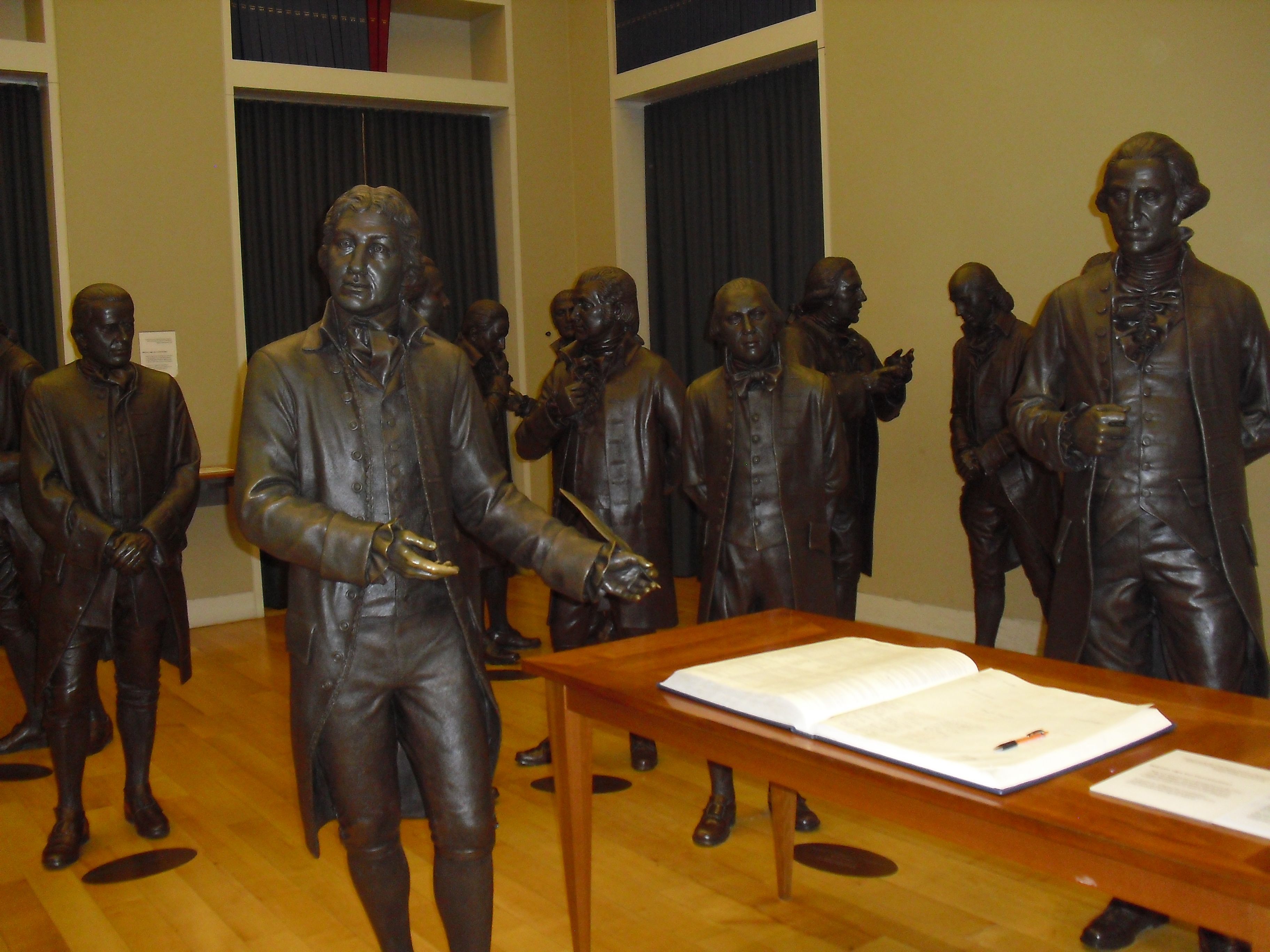

And then visit the men who wrote and signed the US Constitution. In the Signers Hall, 42 life-size bronze statues gather in clusters, discussing, gesturing, urging you to sign their much-argued-over document (in actuality, a guest ledger). Representing a scene in the Pennsylvania State House on September 17, 1787, Signers Hall is one of the most unexpectedly engaging museum exhibits in the city and a worthy photo op. No gadgets, no pulsating lights or sounds. Just statues in a medium sized room. But, mingling among these short, pony-tailed -- albeit inanimate -- men, you can't but feel being a part of history. Before leaving, don't forget to rub the burnished hand or forehead of a seated 82-year-old Ben Franklin, who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution.

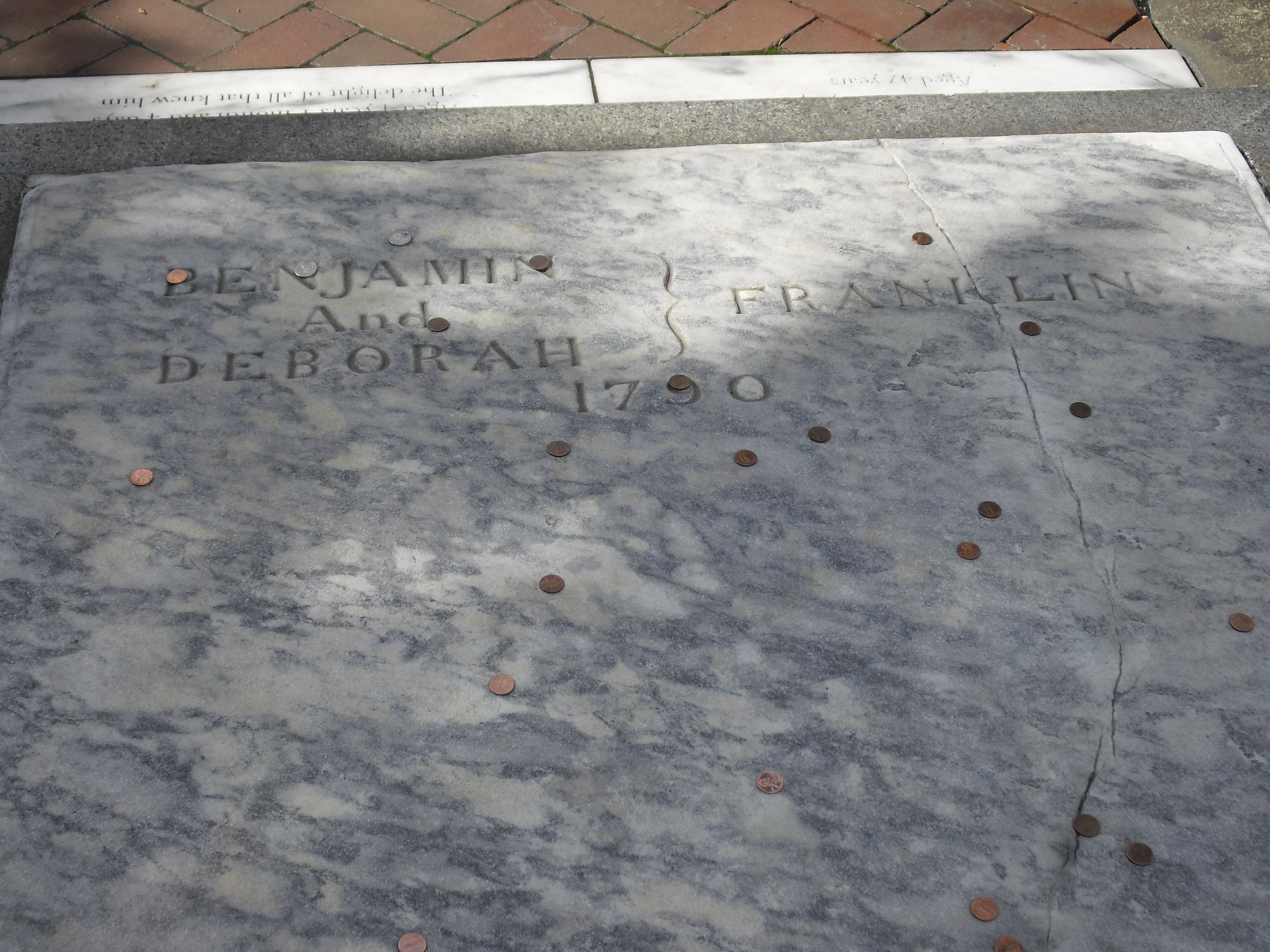

If you'd like to pay your respects to Mr. Franklin, he is buried, along with his wife, a block away at the Christ Church Burial Grounds (5th and Arch St.). Also interred on the two hallowed acres are five other signers of the Declaration of Independence, Revolutionary War heroes and 4,000 other souls. It's worth $5 for a 20 minute guided tour of the cemetery (proceeds help with upkeep), given by "Crypt Keeper," John Hopkins, who mentions that there are three other John Hopkins buried here. You can't miss Franklin's grave, though. It's covered with pennies ("called 'Benny's Pennies'"). Mr. "A Penny Saved is A Penny Earned" is buried right across the street from the very Mint that makes these coins, most of which have traveled all over the world before placement on Franklin's gravestone. Hopkins claims that the Burial Ground collects between $4,000 - $5,000 in pennies every year. Visit Christ Church Burial Ground, take the tour, and throw your own two cents in.

Our Constitution gave root to freedom of religion and equal rights for all citizens, so if you have a few more hours, visit two other exceptional museums; The National Museum of Jewish History and the African American Museum of Philadelphia.

On Independence Mall, the National Museum of Jewish History tells the 350 year old story of Jews in America. In a soaring glass structure (Jews are no longer hidden behind ghetto walls), exhibits begin with the story of 23 Jewish refugees from Brazil who sought freedom in the New World in 1654. Four floors of exhibits illustrate past and present of Jewish life in the US, famous Jewish Americans (like Emma Lazarus, who wrote the inscription for the base of the Statue of Liberty) and current communities.

The African American Museum of Philly preserves, interprets and exhibits the heritage of African Americans. The core exhibit, Audacious Freedom, traces a timeline of African American notables in 1776-1876 Philadelphia.