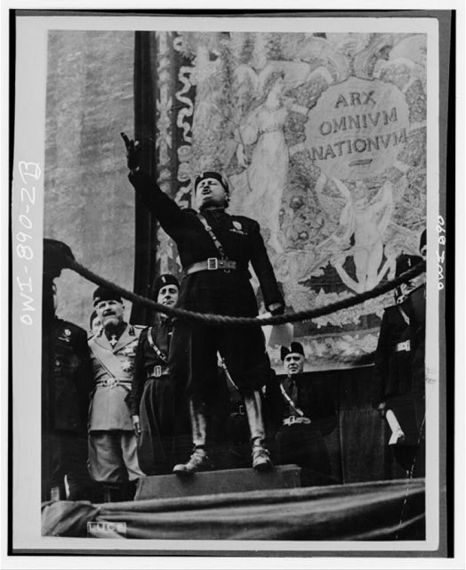

Now that we know Donald Trump is okay with quoting the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, it's probably time to reconsider that old chestnut about those who don't know history are doomed to repeat it. When Trump took Gawker's bait and retweeted a line attributed to Mussolini - that it's better to live one day as a lion than 100 years as a sheep - many Americans were stunned that the leading Republican presidential candidate would pass along a quote from a Fascist dictator. Let alone a dictator whose foolish poses on old newsreels make us laugh. Really, we wonder, who could have taken seriously such a ridiculous man?

But frighteningly, a majority of Americans supported Mussolini for most of his dictatorship. Isolated by an ocean, they fell for his rhetoric.

After the "March on Rome" in October of 1922, in which hundreds of Mussolini's followers demanded a Fascist government and the weak King Victor Emmanuel III relented, America was quick to brand Mussolini a winner. Politicians, journalists, and businessmen believed that Mussolini's new political program, with its brutal intolerance of strikes taking place throughout the country, would restore order and stem the tide of the growing Bolshevist threat.

Americans lapped up Mussolini's rhetoric about restoring the greatness of the Roman Empire. Even the name of his party -- the fasces, a bundle of wheat bound to an ax -- symbolized Roman authority. Finally someone would impose structure on an undisciplined nation and make the trains run on time. Or in Trump parlance, he would Make Italy Great Again.

America's nativist prejudices played into this adoration. Elite Americans had always admired the beauty and artistic achievements of northern Italy, even if they found the people less diligent and hardworking than Anglo-Saxon stock. Their condescending fondness of northern Italy mixed with a growing fear about America's direction due to the mass immigration of poor illiterate southern Italians. Now the moment emerged in which they believed Mussolini could mold an Italy that combined its artistic achievements with their own more rigorous standards of work. It would take a dictator, so this thinking went, to accomplish such a herculean task.

The magazine of Middle America, the Saturday Evening Post, praised Mussolini and serialized his autobiography in 1928. The humorist Will Rogers, after interviewing Mussolini for the Saturday Evening Post, affectionately explained, "Dictator form of government is the greatest form of government; that is, if you have the right Dictator."

The Chicago Tribune similarly praised his authoritarian regime. New York Times correspondent Anne O'Hare McCormick worked herself up to a high pitch of adulation:

"It is easy enough for Americans to comprehend the Fascisti. Direct action is intelligible in any language. A nation that thrilled to the Vigilantes and the Rough Riders rises to Mussolini and his Black Shirt army....Women understand the old-fashioned, masterful sort of government which he re-establishes. They rally to the old-fashioned hierarchies, of religion, authority, obedience which he restores."

The most nefarious aspects of Mussolini's regime were still years away, but each of these journalists turned their backs on the loss of Italy's free press, its wrathful nationalism, the extreme violence of the Blackshirts who beat their opponents to death (or at a minimum beat and force-fed large doses of castor oil to any who showed disobedience), the weekly militaristic rallies for schoolchildren to prepare them for a perpetual state of war, and the placing of faith in a man who radically and opportunistically changed his political positions.

Mussolini had once been a fervent socialist and atheist journalist who denounced capitalists like John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan in his articles about America. The young Mussolini wrote about striking millworkers in Massachusetts, sympathizing with the workers and condemning the "crimes of capitalism." Once in power, however, he abandoned these positions, brutally suppressing strikes and embracing and winning the support of American capitalists and the Vatican. Eventually, the head of J. P. Morgan would become one of his most influential backers.

Only when Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935, his first step in restoring Italy to the greatness of the Roman Empire, did Americans take a second look. When Ethiopia's leader, Haile Selassie, pleaded for the world's help, America was shocked to learn about the Italian dictator's dive-bombing raids and use of mustard gas on the Ethiopian people.

Yet, conservative publications like Henry Luce's Time magazine still had plenty of kind words for the dictator, seeing him as the antithesis of the stereotype of the Italian in America:

Mussolini is a spellbinder . . . [He] is more controlled, more disposed to reticence, less expansive than the average Italian . . . He gives the impression that confidence will be well placed in him, and power turned to good uses . . . It is this un-Italian steadiness which marks him off from the rest.

Mussolini's racial laws of 1938, which stripped Jews of their citizenship and prohibited them from public jobs, skilled professions, and schools, forced Americans to finally comprehend the horrors of the regime they had lauded.

History reminds us that not only the "poorly educated" fall for the inflammatory, belligerent, and contradictory rhetoric of a demagogue whose skill lies in manipulating people's fears. American elites thought Mussolini could stave off the spread of a radicalism that championed immigrants and worker rights. Trump supporters feel economically oppressed and threatened by a disappearing white majority and some Republican leaders are beginning to accept the inevitability of his nomination. Once upon a time, America found itself attracted to the preening strength and false promise of a comic showman. But then again, it can't happen here.