On Saturday, two simultaneous events take place at David Zwirner Gallery in New York -- a wonderful exhibition is in its final hours, ticking down to the last minutes of doors closing; and on the flip side, a celebration of one of New York's most prized postwar artists, putting into focus his career and practice. The artist in discussion is Donald "Don" Judd, a pioneer Minimalist artist who, though he despised being called a Minimalist, culled the very essence of all things beautiful about Minimalism -- form, material, color, scale, surface as the essence, heart and even humanity within a work (despite his railing against art with humanistic content, namely European art, in his 1964 manifesto "Specific Objects"). Donald Judd's clean and perfectly (some critics deemed it "too perfect") aesthetic approach has become as influential and ubiquitous as Warhol's Pop Art. In May, David Zwirner Gallery opened a show of works exhibited in a 1989 exhibition at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden in Germany, grouping together nine (of the original 12 shown) characteristic box-like sculptures made in anodized aluminum, some with brightly colored or black Plexiglas and exhibited with sufficient space around each one. The show has drawn Judd fans from all over the world.

And as an extension to this show, this Saturday the gallery will host screenings of two documentary films about Judd, The Artist's Studio: Donald Judd, produced and directed by Michael Blackwood, and Marfa Voices directed by Judd's daughter, actor and director Rainer Judd for the Judd Foundation. In Marfa Voices, Rainer Judd captures the impact her father had on a small town in Texas -- Marfa, the sparsely populated desert town in southwest Texas that has become well-known within the international art world set, the result solely of her father's presence there, which is now home to one-half of the Judd Foundation (along with 101 Spring Street in SoHo, New York) and the Chinati Foundation. In 1971, Judd started taking his family to Marfa; and by 1979 he amassed 15 buildings that comprised his private living and working spaces. Judd's children Rainer and Flavin were raised between New York City and Marfa but it was in Marfa that they spent most of their childhood. I sat down with Rainer to talk about her father, the Judd Foundation and Marfa Voices, a short documentary that comprises of interviews of those closest to Judd's practice -- selections taken from over 80 interviews that make up the Judd Foundation's Oral History Project, led by Rainer (who also serves as President of the Board for the Judd Foundation).

Trailer, Marfa Voices

Marina Cashdan: The film is, for very obvious reasons, very personal. I suspected that you were behind the camera leading the questions to these interviewees, who ranged from your father's compatriot Jamie Dearing, who worked with your father from the late 1960s until his death in 1994, to Lorina Naegele, your father's gardener and cook.

Rainer Judd: I didn't realize [how heartfelt it was] until more recently when I saw it, because when you're in something you just use what you have and what you can and you're not so conscious of the outcome. I have a big heart and I think it comes out with these people who are talking. It's personal because I know a lot of the people [interviewed].

Donald Judd

© Judd Foundation Archive

MC: It seemed like every person interviewed had a very different relationship with your father. Also, many of the people from Marfa interviewed were at first very apprehensive about modern art and then grew to love it, or your father's work in particular. Did you find it difficult to get stories out of the interviewees?

RJ: Some of them [grew to love his work], and some people who were already very involved with his work. His assistant Jamie Dearing was very much an intellectual comrade of my dad's so he really got it. He showed up for his interview and I said, 'Say your name,' and I don't think we even asked a further question -- or maybe we did ask a question like, 'How did Don get to Marfa?' -- and he went on for about 18 minutes in a beautiful 'Act 1', 'Act 2', 'Act 3' structure of his story. It was like he was a champagne bottle, waiting to say his story. You could tell in the first five minutes whether the person has something to share about their experience. And it's somehow healing to do this thing. It's healing for them, it's healing for the community.

Las Casas Ranch, Marfa, Texas

Photo by Flavin Judd

© Judd Foundation Archive

MC: Can you talk briefly about why you decided to make this film?

RJ: The person who made it originally is co-director Karen Bernstein. She was really the impetus because she had started working with a local radio station in Marfa. I met Karen through a consultant who was working with me to run the foundation when we didn't have an executive director, and she was going to do this radio project. Though I try not to do [personal film projects] with or for the Judd Foundation, I thought you can't interview these people and not see their beautiful faces and who they are! And so it just developed and so we interviewed 30 people in a week in Marfa. And then we decided that we needed at least ten New Yorkers who had something to do with Marfa to help structure the story. And then that was a total of 40 and then we went into editing in Marfa, and we didn't sleep for about five days. The editor had a lot of great ideas and then I had ideas about the story and we just put it together. Since then we've done another 45 interviews.

MC: Was the film created for a particular event, or at that point was it made for no specific intention other than to capture and archive your father's legacy?

RJ: It was created for the [then new] executive director Barbara Hunt McLanahan's first open house, which is a big deal in Marfa, and we wanted to do something more than just open spaces. We wanted to have something to give to the community. It was created for the community. So people who were in the film came and it was like they had been seeing this other person at the post office for 20 years but never knew that they had this story about Don or had a relationship with him, so it was their way of communicating with each other. They got to know what the other person's story was. I don't think they would have told each other these stories or they don't have the venue to talk about it, so they haven't talked about it.

La Mansana de Chinati, "The Block" Marfa, Texas: Courtyard

Furniture: Judd Furniture

© Judd Foundation Archive

La Mansana de Chinati, "The Block" Marfa, Texas

Furniture: Judd Furniture

Artwork: Judd Art/Work © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, NY;

© 2011 Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York;

courtesy of David Zwirner, New York.

MC: So, overall, the community of Marfa had a positive response to the film?

RJ: It created a sense of inclusion and return. We brought these bag pipers down --father and son Joe Brady, Jr. and Joe Brady, Sr. -- that hadn't been there since my father was alive, since '93 or earlier, though Joe Brady, Jr. played at my father's funeral. Somehow people need events and art and literature and film to help you process that everything moves on but you can reconnect and it's ok. Somehow that film was reconnecting people and helping them reconnect with others in their community. But also people want to be heard and want to share their stories. It's amazing that some people came in and didn't think they had something to say but all of the sudden, if you start digging around, it just rolls out.

MC: Will this develop into more short films or a full-length documentary, or just be aural interviews within the Oral History Project?

RJ: That's the magic question. There's interest in making a documentary but there's also interest in making some sort of Web platform where people can access these. Whenever there are funds available we set up interviews but we're looking for more funding, as we don't have a lot of resources to dedicate to this.

The first and foremost thing is to continue interviewing people and then figure out if there's a documentary. The footage is so great and there's so much material for a documentary but it's just about pinning it down and going through it and figuring out what we don't have. The more the foundation's archives are organized, the easier it is for a filmmaker, and the archives are definitely getting a lot more organized, in terms of images. It's also really exciting what you can do with an online system and maybe "Marfa Voices" can be just a chapter.

MC: Your father really brought so much attention to Marfa. What do you think Marfa would be like had your father not gone there?

Art Studio, Marfa, Texas.

Judd Art/Work © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, NY.

RJ: It would probably be like Van Horn [Texas]. There are a lot of towns around like this -- Oklahoma is probably a good example [of a place] where the centers of towns are crumbling and there are decrepit Adobe houses where the toilets are just remaining. I mean Marfa has beautiful architecture so maybe if Don hadn't gone there, people would have gone to Marfa but not in the same way. It's crazy -- you can go anywhere in the world and people know about Marfa.

MC: People in the film talked about your father's presence saving the town and bringing livelihood back. That's quite an impact.

RJ: The whole time my dad was in Marfa it was economically depressed so it didn't really pick up until way past his death. There's a sense of upswing, but whether there's a real upswing, you'd have to ask the people living there. But there are people living there and supporting themselves who wouldn't be had Don not gone there.

MC: Do you ever have feelings that all this attention has not been good for Marfa, maybe making it too tourist driven and not as quiet and humble as it used to be?

RJ: Well I think that Marfa's turning point was when it got cappuccino and salad. I mean salad is a really big deal, which is actually a line in my recent screenplay. The film is through a six-year-old girl's view. There's a line when the little girl is abducted from her school in New York City and brought to a little town in Texas and she asks her dad, "Where is the salad?" And her dad says, "It's too expensive to get here." I think I got that from Roberta Smith; she was talking about how she was in a taxi with my dad and he was saying how expensive salad was and how much it cost to grow salad. My dad had this incredible awareness -- I mean he could buy really expensive Swedish furniture and wine and he would buy fruit like it was flowers, he could spend a lot of money, but at the same time he had this incredible sense of labor and cost and the value of things. He had an awareness of the nuts and bolts. He was from Missouri and he spent summers on his grandma's farm and that affected him.

MC: Can you talk about your relationship to film outside of this project? You're also a screenwriter, aside from being an actor and director?

RJ: I am only writing films that I want to make. I don't know that I would go off and write screenplays for other people. I went to film school and I also went to drama school and I'm just mostly an actor and director who happens to write.

MC: What do you hope the audience will take home with them after seeing Marfa Voices?

RJ: A connection with the people interviewed; a greater understanding of the stories, complexities and evolution of Judd, his work, and the communities of SoHo and Marfa; and in general a greater sense of the passage of time, generations, and heritage.

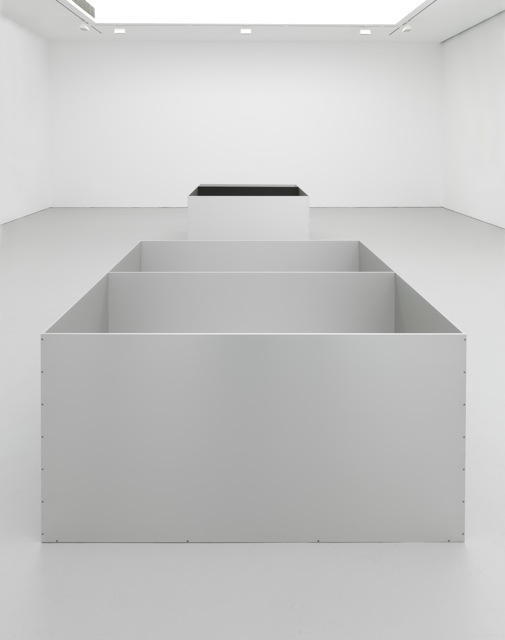

FOUR IMAGES ABOVE: Installation views, Donald Judd, David Zwirner, New York, 2011. Judd Art © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Photos by Tim Nighswander / IMAGING4ART; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York.

Saturday, June 25, at David Zwirner Gallery

525 West 19th StreetThe Artist's Studio: Donald Judd

Produced and directed by Michael Blackwood

10:30am-12:30pm

Film will be shown as a 30-minute loopMarfa Voices

Directed by Rainer Judd for Judd Foundation

1pm, 3pm, 5pm

Each screening will be introduced by the filmmaker, with a Q&A session to follow, and a public reception follows the 5pm screening.Seating is limited and RSVP is required.

Contact Mackie Healy at David Zwirner

212-727-2070 x122 or mackie@davidzwirner.com