With the London Olympics right around the corner, I decided to re-examine the way in which nations are ranked by their medal counts (a "nation" is any entity represented by a National Olympic Committee). Table 1 shows the top 40 nations in the 2008 Beijing Olympics, where the number of gold medals won by their athletes determined the ranking of the nations. Other ranking methods are possible. One could rank by the total number of medals, in which case the United States and China would have switched places, as would have Australia and Germany, among others. But, while ranking by the number of gold medals does perhaps appear to be more appropriate than ranking by the total number of medals (given the much higher prestige of a gold medal), clearly both methods fail to capture the entire picture, or to fairly represent the accomplishment.

Professor of engineering and author Robert B. Banks, who examined this problem in some detail, proposed a few other possible schemes. The simplest of these rankings still use only information on the medals themselves as input, but they assign the three types of medals different values. For instance, a gold medal could be assigned 3 points, a silver medal 2, and a bronze medal 1. Under this scheme, China would have 223 points (from Table 1), and the U.S. 220 points. Or, for the method to at least appear more sophisticated, points could be assigned based on the relative densities of the three metals. The density of gold is 19.30 grams per cubic centimeter, that of silver is 10.49, and for bronze (on the average), 8.50. Calculating the ratios of these three numbers, if we assign 1 point to bronze, silver would get 1.23, and gold 2.27 points. Still more elaborate would be a scheme based on the cosmic abundances of the metals from which the medals are composed. After all, the original 12 Olympians (gods of Greek mythology) were thought to rule the cosmos.

Astronomers have established that there are about 166 atoms of copper in the universe for every atom of silver, and 310 atoms of copper for every atom of gold (bronze is an alloy that is almost 90 percent copper). To make the numbers tractable, we could choose the points assigned to each medal to be inversely proportional to the fourth root of the relative abundances. That is, bronze would get 1 point, silver 3.6 points, and gold 4.2 points.

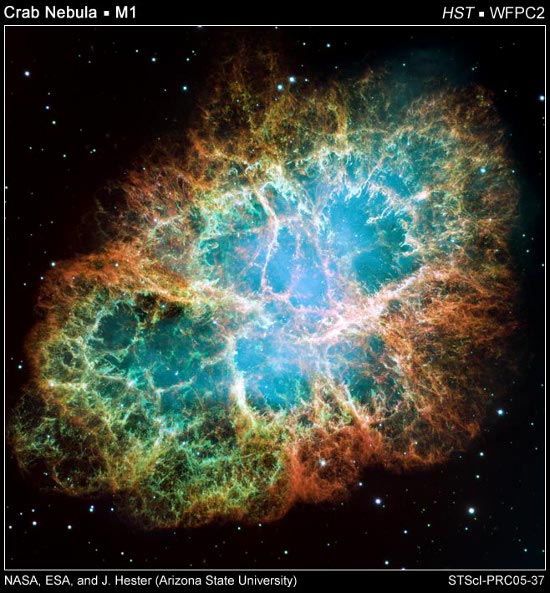

You might wonder where the elements -- copper, silver, and gold -- came from. Copper was mostly forged in the hot cores of massive stars. Silver and gold, on the other hand, were synthesized in huge supernova explosions that marked the deaths of massive stars (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Crab Nebula is the result of a supernova explosion recorded by astronomers in 1054.

All of these methods, however, still don't take into account many other important factors. For instance, there are enormous differences in the populations of the different participating countries (the actual pools from which the athletes are chosen). Also, the differing annual gross domestic products (GDP) per capita probably affect the resources that can be devoted to the training of athletes.

To account for the different populations, one could simply divide the number of points obtained by a nation (by any of the weighting schemes described above) by that nation's population in millions. Hence, the United States' 220 points would be divided by 305 -- its population in millions in 2008 -- giving a value of 0.72. China's 223 points would be divided by 1,328, giving only 0.17, and so on. Robert Banks even suggested a prescription for how one might take the GDP per capita into account. The idea would be to find a functional correlation between the number of points (P) nations achieved in the last Olympics (e.g., Beijing) and the GDP per capita (G). Based on the Barcelona games data, Banks suggested a relation of the type P proportional to G. One can then calculate the "expected" number of points, P, a nation would achieve (based on its G), and subtract that expected value from the actual number of points P the nation achieves. This would measure how nations performed compared to expectations.

While no system is perfect, I hope that this short essay demonstrates how, through the use of simple mathematics, one could devise a more "fair" ranking scheme to evaluate success. Enjoy the London Olympics, and may the best athletes win!