Over the Memorial Day weekend I happened to run across and browse through a new book on the 20th-century Austrian artist Fritz Hundertwasser (1928-2000), whose exhibition I saw nearly 40 years ago. Hundertwasser is one of those artists whose work you either love or hate, but on which it is virtually impossible to stay neutral. While some think that Hundertwasser has been somewhat overrated as an intellectual, there is no doubt that he has left a huge body of work in painting, architecture, and environmental projects, much of which is fascinating. I found three elements in his painting, in particular, to be intimately related (at least to my mind) to current scientific interests.

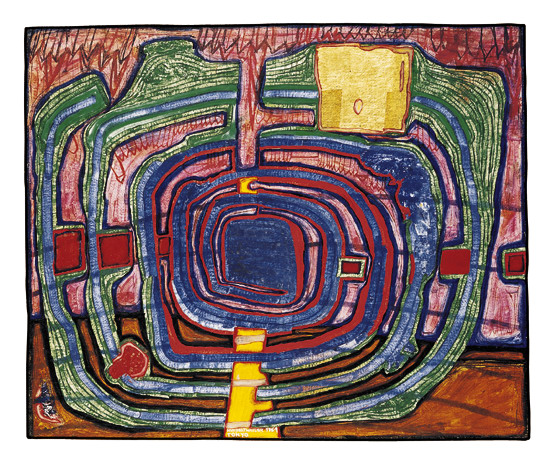

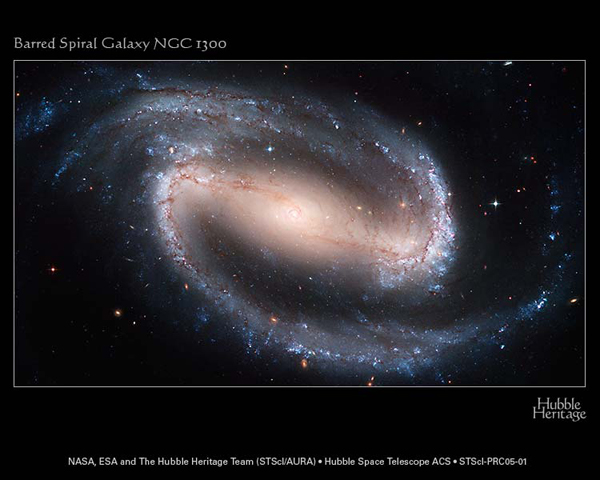

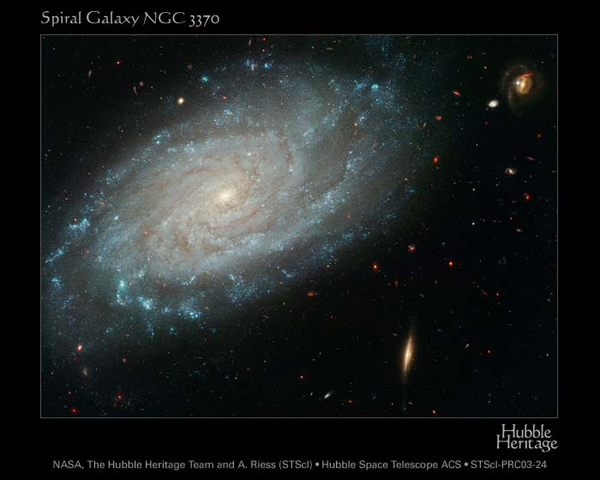

First, starting from about 1953, he became obsessed with spirals, which to him symbolized creation and life (e.g., fig. 1-2). Needless to say, spirals -- or their 3D incarnations, helices -- indeed play a crucial role in the emergence of life, on scales ranging from the molecular (the structure of DNA) to the cosmic (the structure of spiral galaxies; see fig. 3-4). In galaxies, the spiral patterns represent density waves, where new stars and planets are being born.

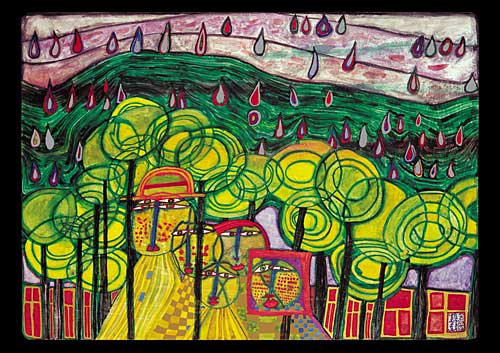

The second prominent element in Hundertwasser's work is water. In fact, he even changed his name from "Stowasser" to "Hundertwasser" (meaning "a hundred waters"), because "sto" means "a hundred" in some Slavic languages. Later, he also added a second last name, "Regenstag," meaning "rainy day," because he noticed that colors glow more vibrantly on rainy days (fig. 5). Modern astronomers are, of course, eager to discover water-bearing extrasolar planets, because water is believed to be a necessary ingredient for life. On one hand, water can act as a solvent, creating a "primordial soup," which gives simple molecules an opportunity to come into contact and form longer chains, and on the other, water can act as a protector from harmful ultraviolet radiation. One of the chief goals of the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), for instance, would be to discover extrasolar planets with liquid water on their surface.

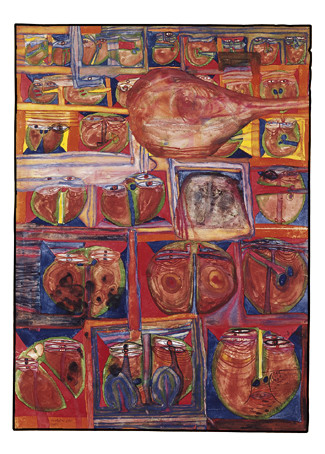

The third characteristic of Hundertwasser's work is what he refers to as "Dunklebunt," meaning "dark colorful" -- he often surrounds saturated colors with a black background (e.g., fig. 6). I don't need to tell you that most astronomical images are naturally surrounded by dark space (e.g., fig. 7). Finally, there is no doubt that in his passion for the environment, Hundertwasser was far ahead of his time -- see his spectacular architectural project in Bad Blumau, Austria (fig. 8).

Figure 1. Hundertwasser, "First Spiral Painted in Japan."

Figure 2. Hundertwasser, Koru flag, suggested by him as secondary flag of New Zealand.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5. Hundertwasser, "The Last Raindrop to Pass By."

Figure 6. Hundertwasser, "Rain."

Figure 7.

Figure 8. Hundertwasser, Rogner Spa in Bad Blumau.