Arguably, the questions of whether extraterrestrial life in general, and intelligent life in particular exist, are two of the most intriguing questions in science today. The discovery (if and when it happens) of extraterrestrial complex life will undoubtedly usher in a revolution that will rival the Copernican and Darwinian revolutions combined. At the most basic level one could wonder what the probability is that the Earth is unique in harboring life. Recent observations with the Kepler spacecraft (Figure 1) and the Hubble Space Telescope (Figure 2) allow us to make at least a rough estimate of this probability.

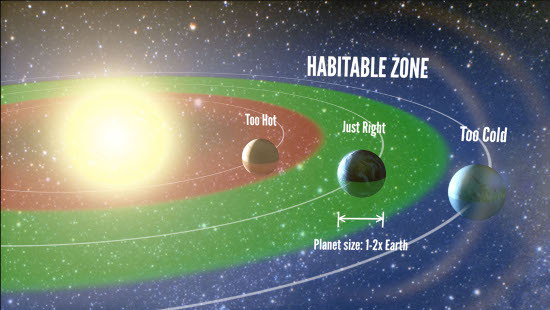

Astronomers using Kepler found that about one in five (22 percent) Sun-like stars in the Milky Way has an Earth-sized planet in the so-called Habitable Zone around that star. The Habitable Zone is that circular band around the star that is neither too hot nor too cold, so that liquid water can exist on the planet's surface (Figure 3). This, of course, doesn't mean that life would actually emerge on such a planet, but a planet in the habitable zone satisfies at least some of the necessary conditions for life. How many such planets exist in the Milky Way? There are about 100 billion Sun-like stars in our Galaxy, which puts the number of "habitable" planets around these stars at about 20 billion. Now, how many galaxies are there in the cosmos? Estimates from the Hubble Ultra Deep Field put that number at about 200 billion in the observable universe. Not all of these galaxies are as large as the Milky Way, but some are much larger. Assuming that on the average about one in ten galaxies is similar to the Milky Way in its contents, we obtain for the number of potentially habitable planets the staggering number of 4 × 10 -- that is, four hundred million trillion. If we now use the law of large numbers, for there to be (on average) only one planet (Earth) with life on it, the probability for a planet to harbor life must be as small as one in four hundred million trillion, or 2.5 × 10. Furthermore, any deviation from this probability (say, by a factor of one thousand, which could easily be possible), would result in there either being no planets with life on them at all, or in there being one thousand such planets. This makes it highly unlikely that we are the only game in the universe.

Figure 1. The Kepler Spacecraft. Credit: Ball Aerospace.

Figure 2. The Hubble Space Telescope.

Figure 3. The "Habitable Zone" around a star corresponds to the region that allows for liquid water to exist on the planet's surface. Credit: Petigura/UC Berkeley, Howard/UH-Manoa, Marcy/UC Berkeley.

The best news that emerges from the Kepler findings is that the abundance of habitable planets puts the nearest one (to Earth) at about 12 light-years away. This makes such planets superb targets for the James Webb Space Telescope (Figure 4) and for future optical-ultraviolet telescopes to search for biosignatures -- signs for life -- in their atmospheres. Still, intelligent civilizations may be rare, which would make the average distance among such civilizations in the Milky Way quite large. In my next blog I shall explore what we might expect for the characteristics of alien life.

Figure 4. The James Webb Space Telescope. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.