When the Dag Hammarskjöld Library at the United Nations announced its most checked out book for 2015 was a doctoral thesis on how heads of state and government officials could be charged in foreign courts, many were taken aback that within an institution making peace its mission, criminal accountability for leaders generated greatest interest. Accountability is not the most popular subject for leaders and heads of state. Institutions, such as the International Criminal Court (ICC) are particularly unpopular. Cases like Prosecutor v. Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta demonstrate the difficulties in holding leaders accountable, the politicization of justice processes, restraint in targeting the largest perpetrators, and a strategy of focusing on smaller rather than larger power blocs in seeking accountability.

When Richard Wilson, Professor of Law and Anthropology at UConn Law School and founding director of the Human Rights Institute at the University of Connecticut, came on April 8 to speak at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice at NYU School of Law (chrgj.org), he elicited our examination of accountability. Accountability is in the terrain of his upcoming book Propaganda on Trial: The Law and Social Science of International Speech Crimes (2016, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), exploring how international tribunals hold individuals accountable for inciting genocide and crimes against humanity.

Wilson began the discussion with a look at the use of historic evidence in trials. In his research, Wilson found that prosecutors often called historians first at international trials. Whereas in national trials, take a murder trial in Miami as an example, calling a historian to testify might seem absurd. In propaganda trials, where there have been 8-10 convictions at the ICC, low-level employees like maintenance worker Joseph Serugendo at Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLMC) were held accountable, reworking Hannah Arendt's banality of evil to the banality of maintenance. In delving into the subject, Wilson saw the ICC's attempts to pursue propaganda as an issue. He then began to ask questions as to where the strategy worked and where it hadn't. These questions included: how did prosecutors bring hate speech experts to ICTY and ICTR trials and why did judges admit their expertise or exclude it? How have international tribunals handled experts brought by the prosecution and the defense? What criteria do international courts use to evaluate the value of expertise?

Wilson looked to the court of the land. Though the United States Supreme Court stated in Daubert its preference for science and evidence that is falsifiable, Justice Rehnquist honestly admitted he didn't really understand what falsifiability meant. It's the same for SCOTUS as it is for international tribunals; as much as these lawyers and judges may like science, in theory, being neither scientists nor mathematicians, can they actually understand it? Or further yet, can they successfully apply it?

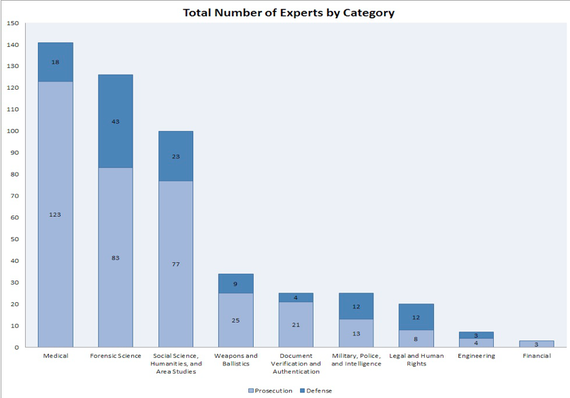

As for allowing the field to speak for itself, in the Ngudjolo case, the ICC decided that scientific evidence is objective, "even if the expert was appointed by only one party or by the Court". Moreover, the experts used widely vary. In the United States, for example, the police are the most common experts called at trials, not scientists. The picture at the ICTY in the Hague looks different, where social scientists are in third place for those most called at trials, and the police at sixth place, the same rank as human rights experts. Not only are social scientists called more frequently, but they are also cited a lot more. Finding that international tribunals prefer qualitative research to quantitative, Wilson examines why that is so in his work, utilizing two specific cases: the Prosecutor v. Nahimana, Barayagwiza and Ngeze in the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the recent Šešelj case in the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) heavily critiqued in the press.

In Prosecutor v. Nahimana, Dr. Mathias Ruzindana, an expert linguist, was called in to provide context for the "Media Trial" in Rwanda. He was able to show that though the accused, RTLM radio owner Ferdinand Nahimana used euphemisms in his speech, it constituted direct incitement to genocide since ordinary Rwandans knew what the words meant: extermination of the Tutsi minority. Ruzindana determined that gukora "to work" in Rwanda at the time meant "to kill". He also determined that both Inkotanyi "warriors" and Inyenzi "cockroaches" referred to Tutsis and the Icyitso "accomplices" referred to Hutu moderates. The Tribunal's primary concern was ascertaining what ordinary Rwandas understood by such terms and the concern served as a test for the case. The judges relied on Ruzindana due to his qualitative and not quantitative expertise and Ruzindana himself approached the judges with the vested knowledge to speak to them as lawyers rather than scientists.

However, in the Vojislav Šešelj case at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, the prosecution's approach was different. Though Šešelj was not a military leader and his followers were not under his official military command, Šešelj was a nationalist politician who had gone to conflict zones to provoke Serbian troops just as they were to set off on missions by telling them of incoming reports of Serbian children massacred by non-Serbs. Šešelj then sent off riled-up Serbian soldiers armed with lies to commit war crimes themselves in retaliation. At his own trial, more a circus than a legal process, Šešelj went so far in his speech as to say that should Kosovo gain independence, the result would be rivers of blood. He also utilized direct speech in calling Croatians poisonous snakes, in stark contrast to the Rwanda media case were such speech was more indirect.

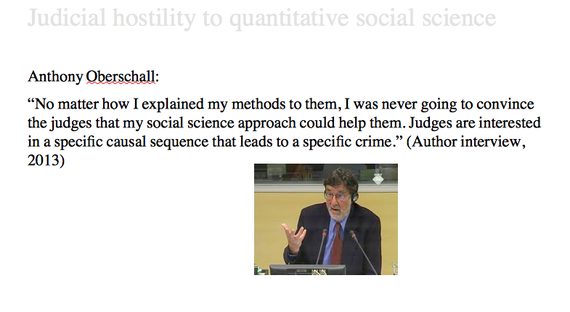

Yet, how did the judges evaluate the expert witness for the prosecution in each case? Wilson shows when expert sociologist Anthony Oberschall was asked by the Tribunal what specific speech caused what specific act, he was unable to show such specificity, stating that hate speech increased the probability that the crime would be committed. Judges were hostile to the answer, unwilling to quantify "beyond a reasonable doubt", preferring rather to answer causation questions with the common sense of the ordinary man. Therein Ruzindana succeeded where Oberschall floundered; Ruzindana utilized non verbose, non-technical language. Oberschall utilized specific numbers. Ruzindana did not discuss causation. Oberschall did.

For Wilson, the legal notions of direct causation are flawed when applied to cases of incitement, where speech is one factor among many and theories of multiple and indirect causation are more appropriate. Therefore Wilson proposes inciters be charged with aiding and abetting an accessorial liability rather than direct instigation which requires that a speech act directly cause a criminal offence.

For Wilson, the judges' standards required unrealistic fact patterns that ignore foreseeability. When I asked Wilson his views on hate speech, he replied that his work pushed him personally towards a very low tolerance for hate speech in the media, but legally speaking, he still leaves open the question of how it should be criminalized, explaining that when members of ethnic, religious, and racial minority groups are persecuted, hate speech creates conditions in which hate and even violence are more likely to be morally justified. If we were bombarded with hate speech for two weeks, would there be physiological effects on us? Would we be more likely to be aggressive upon encountering the target of that hate speech? When speech like that of Donald Trump escalates and we see a presidential candidate who promises to deport 11 million Latin Americans, where does accountability for incitement lie?

As such, Wilson advocates for examining the speaker's intent in cases of incitement to genocide, removing the intent of the speaker from the consequences of the speech. By looking at the content, meaning, and force of speech, instead of its outcomes, efforts can be refocused on genocide prevention and refocusing accountability so that instead of holding low-level maintenance staff accountable, individuals like Šešelj would have to answer for their actions, rather than further run for elections.