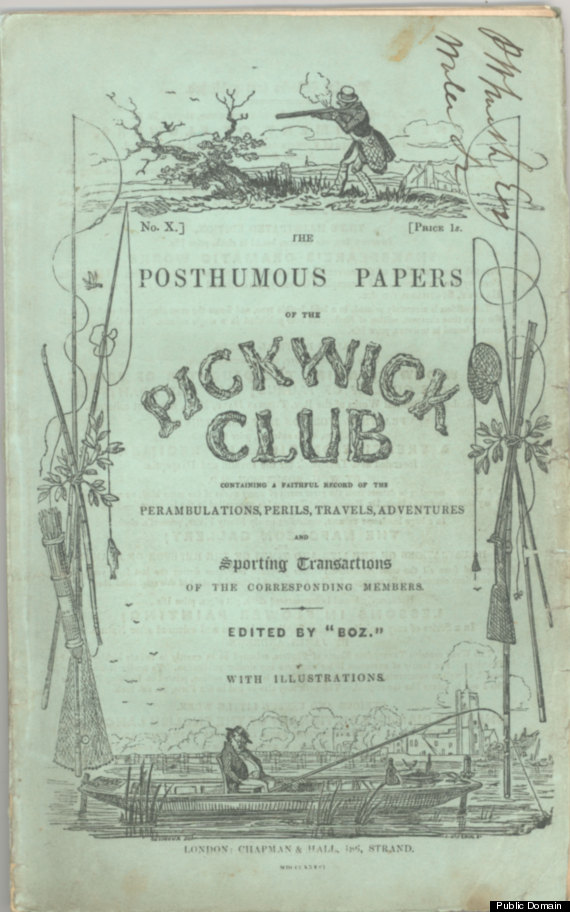

When Dickens serialized The Pickwick Papers in 1836, droves of readers crowded the docks to get the latest installment fresh off the boat--not unlike the excitement you'd have seen at a midnight release of Harry Potter.

The serial novel wasn't new in Dickens's day, but he kicked off a prodigious new way for vast numbers of readers to experience--and buy--a book. Harpers, Atlantic Monthly, Scribner's Monthly and other periodicals reached hundreds of thousands of readers and went on to propel the careers of Herman Melville, Henry James, Arthur Conan Doyle, and many others to unprecedented popularity.

The serial idea has had many incarnations, including in magazines, comics pamphlets, TV and film media. Its latest rebirth is a phenomenon that, until recently, went largely unnoticed by conventional publishers, and yet has the hallmark of a true revolution: the serial webcomic.

From personal computers in all parts of the world, hitherto unknown comics artists have attracted faithful readers in numbers that are baffling.

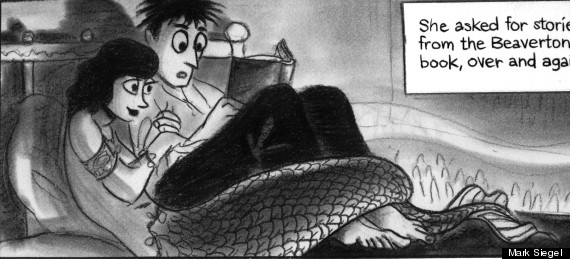

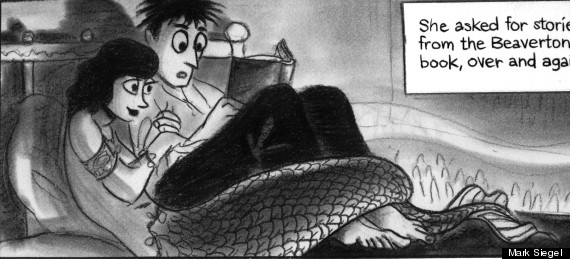

My own experiment in this took place over two years with a project called Sailor Twain, or the Mermaid in the Hudson. I knew little of webcomics before I launched sailortwain.com, at a rate of one new page every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. 800,000 unique readers later--months before the book's release--a community had grown around the project, and all kinds of unexpected surprises had peppered the journey.

© Mark Siegel, Sailor Twain, or the Mermaid in the Hudson

The first thrill was the immediate interaction of course. Beforehand, I had no idea whether, in our age of instant online gratification, anyone would join a slow-building supernatural romance set in 1887 New York, drawn in old-fashioned charcoal and spread out over 400 pages. Turns out many did. Next the "onboard conversation" drew in all kinds of readers, history buffs, steamboat geeks, Jane Austen readers, and a host of others who don't ordinarily read comics, let alone webcomics.

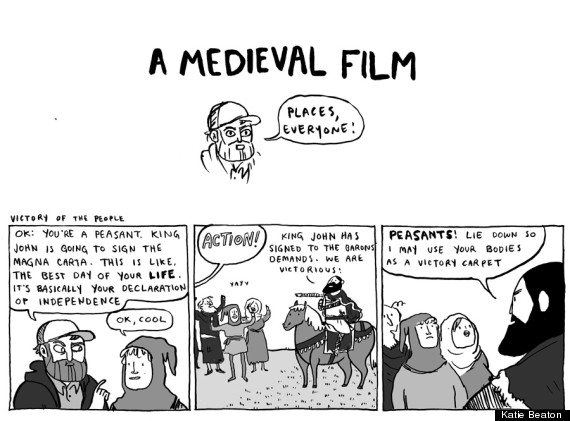

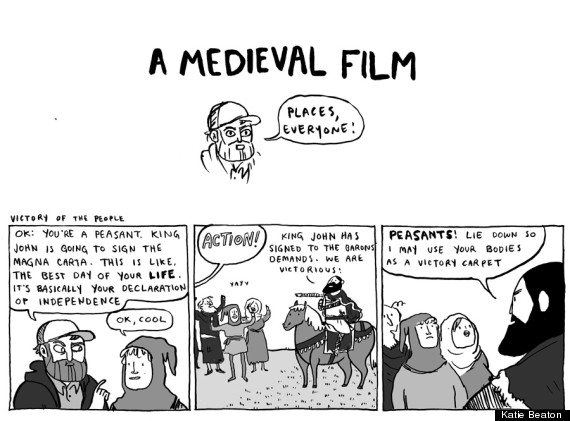

Sailor Twain hardly topped any charts among webcomics. Though they get little coverage in mainstream media and belated attention from big publishing houses, the webcomic has exploded on the internet--some of the most popular ones, among my favorites XKCD (drawn in stick figures!) and Kate Beaton's hilarious Hark! A Vagrant for instance, count their steady hits in the millions.

© Kate Beaton, Hark! A Vagrant

Some webcomics authors go on to very lucrative publishing deals for the print version of their project. The fact some of them sell tens of thousands of copies of their books--with first in line, their online fans--turns more than a few conventional publishing wisdoms on their head.

Other webcomics authors make a handsome living from merchandising prints, T-shirts and toys on their site; others yet take the Kickstarter route. There again, crowd funding--when it takes off--boasts loyal, paying crowds that muster more than a publisher's advance likely would. Take for example the talented Gigi DG, who set out to raise about $10,000 to self-publish her exquisite Cucumber Quest: long before the deadline, she drew in $62,953. Or look at Jake Parker, who went to Kickstart his comics anthology The Antler Boy; he asked for $6,000 and wound up raising $85,532 in pledges.

© Gigi DG, Cucumber Quest

These are but a few of the teeming signs of something big happening under our very noses. There are many more, in all age categories, in all styles and genres, from short gag strips to epic, ambitious long-form narratives. The internet has become the medium for the serial novel of our time.

Unlike with Dickens when the only response was the letter to the editor, readers are now participant voices who can chime in alongside and often directly with the author, in near-real time. The new serial revolution is also an experiment in community-building that way.

In the 1800s we flocked to the docks. Today we have an RSS Feed.

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

It's Another Trump-Biden Showdown — And We Need Your Help

The Future Of Democracy Is At Stake

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

Your Loyalty Means The World To Us

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

The 2024 election is heating up, and women's rights, health care, voting rights, and the very future of democracy are all at stake. Donald Trump will face Joe Biden in the most consequential vote of our time. And HuffPost will be there, covering every twist and turn. America's future hangs in the balance. Would you consider contributing to support our journalism and keep it free for all during this critical season?

HuffPost believes news should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay for it. We rely on readers like you to help fund our work. Any contribution you can make — even as little as $2 — goes directly toward supporting the impactful journalism that we will continue to produce this year. Thank you for being part of our story.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

It's official: Donald Trump will face Joe Biden this fall in the presidential election. As we face the most consequential presidential election of our time, HuffPost is committed to bringing you up-to-date, accurate news about the 2024 race. While other outlets have retreated behind paywalls, you can trust our news will stay free.

But we can't do it without your help. Reader funding is one of the key ways we support our newsroom. Would you consider making a donation to help fund our news during this critical time? Your contributions are vital to supporting a free press.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our journalism free and accessible to all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you'll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.