"Too many American children are segregated into schools without standards, shuffled from grade-to-grade because of their age, regardless of their knowledge. This is discrimination, pure and simple -- the soft bigotry of low expectations.''

-- George W. Bush, accepting Republican nomination for president in 2000.

The candidate's sentiment, first uttered during a September 1999 campaign speech to the Latin Business Association in Los Angeles, bore the unmistakable ring of a speechwriter's rhetoric, a fine turn of language by a hired political wordsmith.

Yet it resonated with this reporter taking notes at the time, a reporter who'd once asked the chief academic officer of Miami-Dade County's school board to explain the discrepancy in test scores between suburban and inner-city schools. It was a harsh fact, he said, that the socio-economic status of any school's students had a direct relationship to their test performance.

This, in a county where a federal judge had long before concluded that Miami's schools were so racially segregated that it would be infeasible to realign them with busing, a sub-tropical county where half of the city's public schools lacked air conditioning well into the 1980s.

This was in the days before America's long wars -- when Americans were hearing of another war on their own shores. Governors were beginning to understand the depth of a problem within their own states, a recognition of failing schools gaining traction nationally. In April 1983, the National Commission on Excellence in Education, in its report entitled "A Nation at Risk," warned: "If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.''

By the 1990s, enough progressive Southern governors had come to understand the challenge that campaigning on educational reform was becoming worth the effort. It paid off at the ballot box.

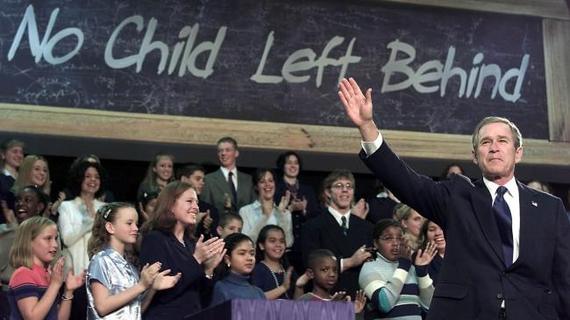

George W. Bush won election as governor of Texas in 1994 with a plan for improving the state's schools, while brother Jeb Bush lost his first bid for governor of Florida that year campaigning with a promise to get tough on crime. Jeb came around in his second go-round, winning election in 1998 with an "A-Plus Plan'' for education based on holding schools accountable for their students' performance. And his older brother carried the flag to Washington, winning passage of his No Child Left Behind Act his first year in office.

The law, a rewrite of the basic Elementary and Secondary Education Act which already had been steering additional federal funding to schools with impoverished students, required the states to test students annually in reading and math each year from the third through eighth grades and once in high school. Schools that weren't making "adequate yearly progress'' on standardized tests for two years in a row would have to allow students to transfer out. After six years of failure, they could have their staffs replaced, taken over by the state or turned into charter schools.

Its adoption became a signal bipartisan achievement. The Republican-run House approved it 384-45 in May 2001, the Democratic-run Senate 91-8 in June 2001. Both Sen. Ted Kennedy and Rep. John Boehner were on board, and 14 years ago this week an agreement over differences in funding was resolved. Bush signed it into law in January 2002, as the nation's attention was turning to terrorism.

Evidence of success or failure is said to be mixed. Scores on a national assessment test have increased modestly in both math and reading in elementary and middle schools -- though scores already had been rising. Yet the percentage of schools not making adequate yearly progress increased from 29 percent in 2006 to 48 percent in 2011.

In the latest edition of "The Nation's Report Card,'' with results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the Department of Education reported that, in math: "The 2015 average scores were 1 and 2 points lower in grades 4 and 8, respectively, than the average scores in 2013. Scores at both grades were higher than those from the earliest mathematics assessments in 1990 by 27 points at grade 4 and 20 points at grade 8.'' In reading: "The 2015 average score was not significantly different at grade 4 and was 2 points lower at grade 8 compared to 2013. Scores at both grades were higher in 2015 than those from the earliest reading assessments in 1992 by 6 points at grade 4 and 5 points at grade 8.''

And: 51 percent of the white fourth-graders tested at or above proficient levels, while 19 percent of black fourth graders did. In eighth grade, 43 percent of the white students and 13 percent of the black students tested proficient or better.

On a parallel reform track, so-called "Common Core'' standards were born of a report initiated by another governor, Democrat Janet Napolitano of Arizona, who went on to become secretary of homeland security and head of the University of California system. As chairman of the National Governors Association, she created a task force of commissioners of education, governors and corporate CEOs which in December 2008 produced the foundation of what became known as Common Core State Standards adopted by 45 states and the District of Columbia.

Yet, in a few short years since then, a perfect political storm of conservative reaction and liberal outrage has undone the entire framework. As eagerly as the Common Core regimen was embraced, it was disavowed in a Tea Party-inspired wave of opposition to what was become known simply as government over-reach. And as strongly as the teachers' unions had campaigned for educational reform, they deemed the government's obsession with testing an albatross hanging over the careers of educators who could handle their own classrooms perfectly well.

Today the Senate thoroughly revamped the No Child Left Behind Act while maintaining a basic requirement for testing. If the law's adoption was bipartisan, so was its repeal. Its successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act, cleared the Senate 85-12, after winning passage in the House by 359-64 a week ago. President Barack Obama will sign the bill in the morning, according to the White House.

The old law, which technically expired in 2007 but lacked a replacement, already had started unraveling. Starting in 2013, the Obama administration was offering states waivers enabling them to avert the law's penalties so long as they adopted their own standards. Forty-three states, and Washington, D.C., won those waivers.

The new law still requires annual testing in reading and math for students in third through eighth grades. But it leaves the mechanism and measurement of success to the states. One writer, Libby Nelson, at vox.com notes: "This is a major victory for the conservative vision for education policy, which puts the states, not Washington, in charge of holding schools accountable -- and it means states could scale back their efforts to improve schools for poor and minority children.''

It includes one safety net: Requiring states to intervene to improve the bottom-scoring five percent of schools, high schools with graduation rates under 67 percent and schools where certain subgroups of students -- read minorities -- are persistently falling behind.

"Wherever those inequities persist, the federal law demands that we see real action," Duncan said. "It requires that local leaders act to transform the odds for students in their schools."

Sen. Lamar Alexander, the Tennessee Republican who served as secretary of education from 1991-93 and chairs the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, said in a statement following passage of the new law: "By restoring responsibility to states and classroom teachers, we are inaugurating a new era of innovation and excellence in student achievement.. It will end the federal Common Core mandate... It moves decisions about whether schools and teachers and students are succeeding or failing out of Washington, D.C., and back to states and communities and classroom teachers where those decisions belong."

No longer, Alexander says, will a federal government holding financial sway over states and communities serve as "the national school board.''

That duty will be left to the states, including the ones that have written evolution out of their textbooks. And it will be left to local school boards, including the ones that decided many years ago that some schools simply couldn't be racially integrated, some were fine for a long time without air conditioning and test performance was mainly a matter of which part of town you came from.

The rhetoric surrounding the new law is relatively restrained. We didn't hear any talk of bigotry today, only an expectation that communities across America will step up to that challenge of righting a system of education which, if imposed upon us by a foreign power, would be called an act of war.

It's back to the chalkboard in public education -- or the digital projection screen in the better schools. America's schools are on their own again, where they started.

(Photo of George W. Bush at signing of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002 by Tim Sloan/AFP via Getty Images.)