About a week ago, on ABC's This Week, Mme. Huffington told Roger Ailes that language matters. It certainly does.

So much so that it deserves its own regular featurette. And since that's one of our chief preoccupations at LiteralMayhem, we offer you:

Language Matters: an occasional series on the use, abuse, and impact of language

As a first subject let's take the current Great Recession. We know that "housing" was the pin in the hand grenade. But how did "housing" get so out of control?

There's No Place Like "House"?

At some point around the turn of the millennium, "home ownership" turned into "house ownership" and that, my friends, was the beginning of the end.

It used to be that owning your own "home," with all the attendant warm-and-fuzzies, was the foundation of the American Dream. In the post-war years it was emblematic of the rise of the everyman in a new social order where stability and success were available to all -- stable communities, rising standards of living, and the flowering of families into lives full of possibility. Think: Mayberry.

Sure people like William Levitt turned home building into a volume business, maybe even into a commodity business. But Levitt was still building "planned communities" -- he wasn't building "planned tranches of securitized regional mortgage pools."

Well before Levitt's day, during the 19th Century "homesteader" movement, all one needed to establish ownership of property was to mix one's labor with the land. The government codified this idea with The Homestead Act of 1862, and distributed 80 million acres of public land to private settlers in just under 40 years. The movement was based mostly on romantic (and chauvinistic) notions to be sure, Manifest Destiny and all that.

But generally speaking, the American fascination with "home" had always been rooted in some idea of the life one could build there - the idea of planting yourself somewhere, then mixing in hard work and aspiration, and seeing what might grow.

And Then Came Greenspan

Then at some point, ideas changed -- and so did the words that went with them.

Owning a "home" was much less about building a life, and more about purchasing a living structure on a piece of property that was a valuable but illiquid asset. In other words, it was just a "house." Sticks, bricks, and grass (if you're lucky) ... with a line of credit attached instead of a garage.

And your "house" -- as opposed to your "home" -- was a source of wealth that the government was bound and determined to inflate with monetary policy. In August 2001, after the tech-bubble went bust, Alan Greenspan made this observation (NY Times):

''I think one of the things that's occurring in the country,'' Mr. Greenspan said then, ''is the evolution of housing into a very sophisticated, complex industry, in the sense that we not only have got standard home-building aspects of home-ownership-related activities, but we're also beginning to find that as home ownership rises and as the market value of homes continues to rise, even in a period when stock prices are falling, we're observing a rather remarkable employment of that so-called home equity wealth in all sorts of household decisions.''

A portfolio manager at the giant bond house PIMCO observed:

''Greenspan is bound and determined that he is going to nurse this thing along by creating a positive wealth effect for housing.''

And so it had begun: "the evolution of housing into a very sophisticated, complex industry."

The focus on community, on refuge and rest, on having a "home base", on a place of abiding, a place of autonomy, a place of domesticity, a place of living... all these and many other values associated with owning your own "home" began to erode, or at least fade in importance behind another more important reality: a house as a cold hard asset that you could treat like a credit card.

Chickens Come "Home" to Roost

In the post-war years, as Mayberry and Levittown grew and grew, and more average Americans bought their own "homes," homeownership in the U.S. rose sharply.

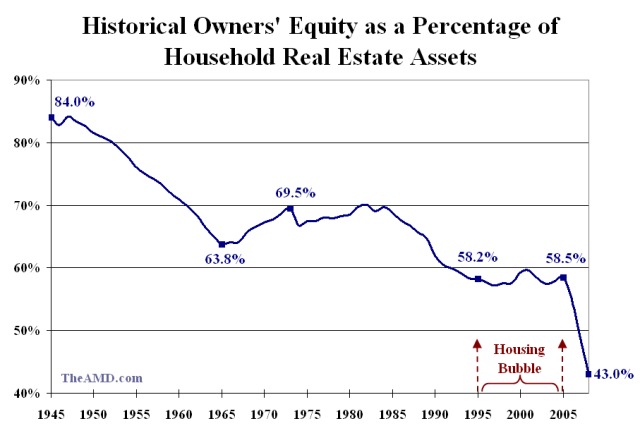

But average homeowner equity was moving in the exact opposite direction - due to rising loan-to-value ratios, as well as a government push behind longer loan terms and fixed interest loans. Before the Great Depression, mortgages were generally high-downpayment, short term, variable interest loans that were constantly refinanced... and unaffordable to most Americans.

When you compare both graphs you can see that somewhere around the mid 1960s, ownership and homeowner equity both started to flatten, as loan standards converged on a 30-year fixed term and average loan-to-value ratio of about 80%.

Funny thing though, this explosion in homeownership didn't cause a financial meltdown and nearly destroy the world. So why was the past 20 years so different?

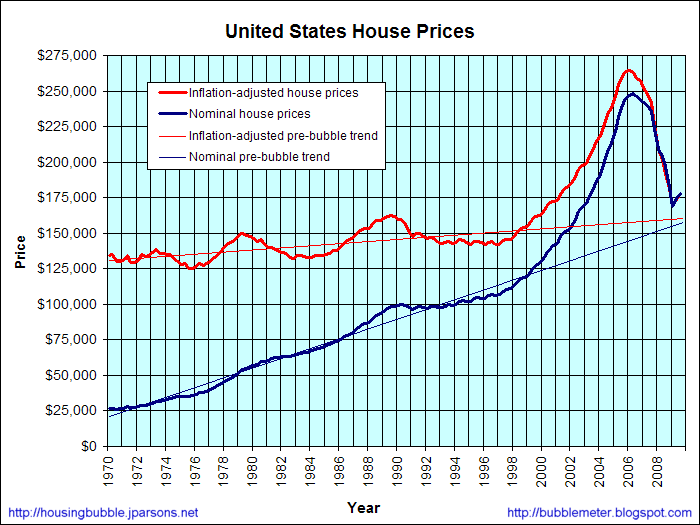

Two primary reasons (but housing experts please feel free to weigh in with more): Homeowner equity remained flat from 1995 until about 2005, even as prices were skyrocketing way above their historical trend lines:

In plain English: While housing prices were on fire, people were taking out all their gains and spending them.

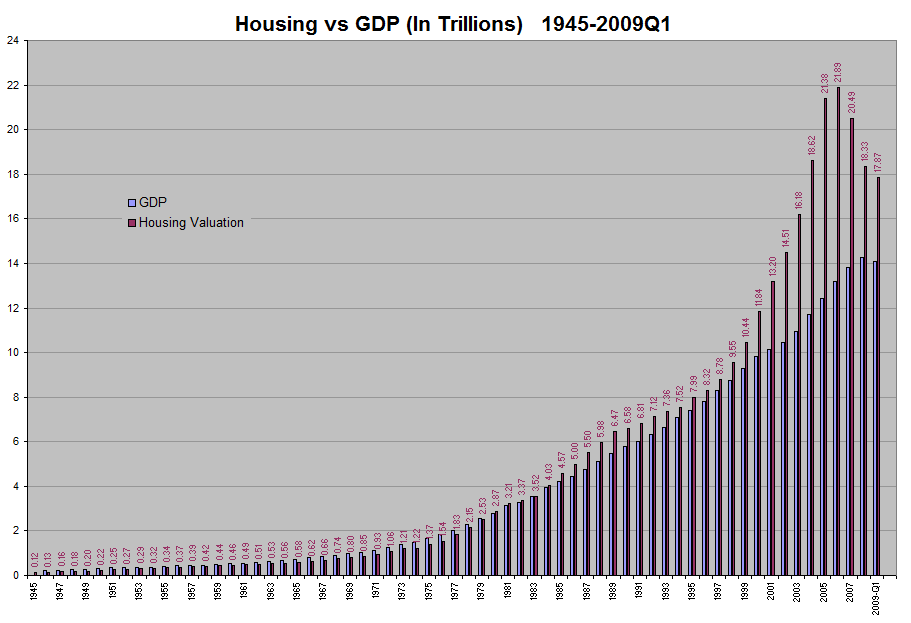

At the same time, the "housing" wealth effect (which Greenspan was trying so hard to pump up) started to outstrip GDP by a frightening margin. You can see in the chart that in 2000/2001, it was like someone (ahem, I'll give you one guess) lit a fire under house prices.

It's no wonder that in their 2001 article, the Times made a point of tempering Greenspan's irrational exuberance about "the evolution of housing into a very sophisticated, complex industry":

''If the housing market takes a hit,'' we will be in trouble, said Jay Mueller, an economist at Strong Capital Investment. ''But if the broad measure of housing across the country holds up, it will continue to support the economy.''

Presumably, this is why interest rates have to remain low for a long time, to keep the housing market healthy, unrealized capital gains rising, and a sense of the wealth effect intact.

Of Hearth and "House"

The most ironic part of the "housing" boom -- and of Greenspan's efforts to pump up the housing wealth effect -- is that "homes" are actually a terrible "investment."

If you don't believe me ask a Fed economist (WSJ)

Karen Pence, who runs the Federal Reserve's household and real estate finance research group, argues at the American Economic Association's meetings this week that homes are actually a terrible investment. Putting aside the fact that home prices have fallen dramatically, she says several factors make homes a lousy investment:

- It is an indivisible asset.

- It is undiversified.

- Transaction costs are very high.

- It is asymmetrically liquid.

- It is highly correlated to the job market.

For more than two decades government policy was hell-bent on feeding the idea that a "housing" was a complex and sophisticated industry -- one that could support endless national consumption and an alchemical approach to financial innovation that created gobs of wealth out of mere ownership.

What we got -- when a "home" became merely an asset called a "house" -- was an asset bubble just like any other. And as a result, many people are not just threatened with losing their assets (i.e., their "houses") but also their intangibles: their "homes" and the lives they have built there.

The Pandora's Box of "Housing"

When something is warm, comfortable and cozy we say it's "homey" -- not "housey." Your ultimate goal after tearing around the bases is to make it safely back to "home." You fill up on "home" cooking, and when you find a safe place to rest your head while on the road, it's a "home away from home," until you can make it back to "home sweet home."

All the dimensions of the experience of "home" are completely meaningless to an amoral and impersonal market. A "home" can't be packaged and sliced and sold and re-sold. A "home" has no equity against which you get a HELOC to buy a car or a marble vanity for the master bath. A "home" is not a source of worldly riches.

A "house"? Well that you can slice and dice, and borrow against, and aggregate, and securitize, and derivative-ize, and do all kinds of other whiz-bang financial wizardry with.

And this is why language matters: it is a window into the inner workings of the mind; it's a clue to how we think about things; it defines our reality, and in doing so it sanctions certain decisions while obviating others.

Our change in language reflected a decision we made: to part ways with a longstanding notion of "home" and replace it with a more fungible and commoditized idea: that of a "house" as an asset we reside in. Our choice had undeniable benefits, for a while. But now we are seeing - nay, feeling the effects of the trade-off, beginning to see what we gave away.

And if you need further evidence as to the importance of a change in mindset -- and the relationship of language to (ahem) reality -- consider the Fed economist Karen Pence, who said that a "home" is a lousy investment. Well, she admitted to the WSJ reporter that she is looking to move out of her apartment and buy something, because "her husband wants a dog and wants to start gardening."

Is she looking for a "house," or an "investment," or an "asset," or a source of "wealth" that she can treat like an ATM?

No, she's not looking for a divisible, diversified, symmetrically liquid asset with low transaction costs that's inversely correlated to the job market.

What she's really saying is that she wants to buy a "home."