On City Cisco Island, Aunt Suzy saw funny men.

That sentence is a mnemonic that Mr. Jaeger taught us. The first letter of each word stands for a molecule in the Krebs citric acid cycle, the pathway that converts food to energy. The O in "On" stands for Oxaloacetate; the C in "City" is Citrate; the next C is cis-Aconitate -- all the way to "men" and Malate, which circles back to Oxaloacetate.

Why do we need to know? Mr. Jaeger taught us that, too. Actually, he taught it twice. Once was in class, Advanced Biology, where I was one of a couple dozen Union (N.J.) High School seniors. The second time was before dawn. It was cold and dark out, but we made it to school, Mr. Jaeger drove in from Staten Island, where he lived, and for an hour before homeroom, every morning from winter to spring, he did everything humanly possible to prep us for the Advanced Placement test in biology.

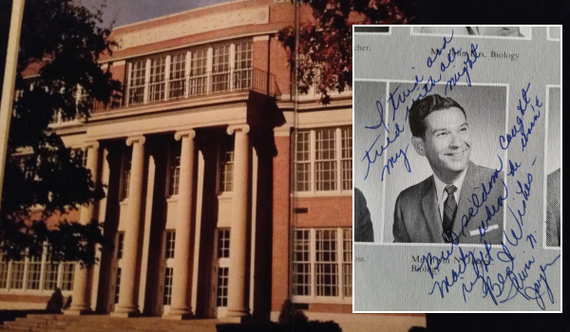

He did it year after year, decade after decade, for one generation of students after another. And he didn't just teach biology. He modeled what it means to love your work, what passion for truth looks like, what dedication can accomplish. When we graduated, he wrote in each of our yearbooks: "Excelsior -- never be content with mediocrity." And "Scientia est potentia." Knowledge is power. And he signed it, Irwin Norman Jaeger.

Mr. Jaeger died last week at 81. I was fortunate to have had other fine teachers in high school, and I had some awesome professors in college and graduate school, too, but Mr. Jaeger was the life-changer, the best teacher I ever had, and from the tributes to him I'm reading on Facebook, it's clear I'm not the only one who feels that way. I wouldn't have had the education I had after him if he hadn't coached me to apply to the best colleges in the country and patiently told me, a higher education greenhorn, which ones they were.

He was the first teacher to show me the frontiers of knowledge. I didn't know it at the time, but when I was in the eighth grade, J.D. Watson and Francis Crick won the Nobel Prize for figuring out the structure of DNA, which they (and Rosalind Franklin, who had died and so was ineligible) had unraveled only nine years before. The genetic code, the mechanism of heredity, the molecular basis of life: most of modern biology is a consequence of their discovery. When Mr. Jaeger taught us about DNA's double helix, it was the biggest, most mind-blowing news I'd ever heard, and I couldn't wait to tell everyone I knew. And when Mr. Jaeger pointed out that J.D. Watson was an actual living person on the Harvard faculty, I knew exactly where I wanted to go to college and what I wanted to do there. Ten months later, I was working in Watson's lab.

It then took me three years to go from being what I thought was Mr. Jaeger's biggest success story to being what I was sure was his biggest failure.

Like almost everyone else in his Advanced Bio class, I got a 5 on the AP test; combined with decent showings in AP physics and math, I took advantage of Harvard's offer to skip my freshman year and plunge right into molecular biology. It was an amazing era for the field, and I was lucky to be assigned as a tutee to a post-doc in the Watson group whose research was so productive that it spun off other projects, one of which I was invited to grab on to as my own. In the summer, I worked at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory of Quantitative Biology, which Watson ran, and my senior thesis -- "Transcription Specificity Conferred by the RNA Polymerase Sigma Factor" -- clinched a summa cum laude degree. But by then, there was one thing I was sure of: I had to get off the path Mr. Jaeger had opened to me.

Until I faced up to that, I loved visiting Mr. Jaeger when I went home for holidays. His face lit up when I told him about goings-on in the lab. The pride he took in me made me soar; I was thrilled to have something to show for what he'd given me, and to express my gratitude to him. So in my senior year, when I realized that I was never going to be a molecular biologist, cure cancer or win the Nobel, what scared me even more than my cluelessness about what path to take instead of science was telling Mr. Jaeger.

Even today, I barely understand what made me want to leave the lab. Part of it must have been the times. I hadn't paid much attention to politics when my eyes were on the Prize, but the war in Vietnam, the war on campus, the collapsing legitimacy of values and institutions: I finally couldn't ignore the revolution going on, and I felt compelled to be at the barricades. (Okay, there was the sex, drugs and rock and roll part, too.) But what most threw me off course was realizing that I was a kid committing myself to one particular life before I knew much of life at all. It was a glorious accident that I had Mr. Jaeger, that my huge public high school was where he spent his career. What if my favorite teacher had taught U.S. History or English? Would it have made any more sense to take a vow at 20 to a career in government or literary criticism? I didn't have a better idea than molecular biology, but I also didn't want to wake up in a cold sweat at 30 or 40, stranded, and think I'd made a terrible mistake because I'd decided too soon.

I needn't have feared Mr. Jaeger's reaction. He was as supportive of my confusion as he'd been of my commitment. What I didn't understand then was that he'd already had plenty of students who'd changed direction, and what I've only realized this past week, reading what people have been saying about him on Facebook, is how many students he inspired to lead successful, meaningful careers not only in all the sciences and medicine but also anywhere where knowledge truly is power and mediocrity is always unacceptable.

Maybe not everyone had a Mr. Jaeger to open their minds to wonders they never knew existed, and to find gifts in their head, stamina in their gut and hopes in their heart they didn't know they had. But if you were lucky enough to have at least one teacher like that, I hope you were able to tell him or her how grateful you are before it turned out to be too late.

_______________

This is my column from the Jewish Journal, where you can reach me at martyk@jewishjournal.com.