As the pictures and reports of the first Nepal earthquake began to emerge, news from Kathmandu was horrific, an unimaginable destruction of people's lives, homes, and cultural histories. But later hearing that Barpak and Gumda were at the epicenter gripped me even more tightly with a feeling of helpless despair.

Over 30 years ago I led a team of Nepalis going village to village in rural Gorkha district providing immunizations, health education, and some medical care for the rural populations. The villages of Barpak and Gumda were the farthest north we went in Gorkha, nearest to the staggeringly beautiful Himalayas. My last official assignment took me to Barpak, three days' trek north from Gorkha village. From there we traveled on to Gumda, several more hours' walk away on beautiful rhododendron-lined trails.

Gumda was a small village with sturdy flat-roofed houses made of local stone, the streets packed with children who spoke only their local language. As in most places, women walked long distances to carry water to their homes, the trails were steep, and much of the land was not suitable for crops. But they were cheerful and industrious in spite of those challenges.

As we entered the village I could see Ganesh Himal, a shining peak that jutted up at a right angle, looking like a children's drawing of a mountain. Shortly after we set up camp, a young Nepali man dressed in a sparkling white shirt and black slacks approached me and introduced himself as Sailendra, the medical assistant for that area. Sailendra explained that he was what in the U.S. would be a "physician's assistant" -- although in Gumda there were no physicians to assist for many days' walk away. After one year's training, he had been placed on his own in this remote rural area, far from his home, with minimal supplies and equipment and essentially no backup. He didn't speak the local language, so he had to do much of his work with an interpreter.

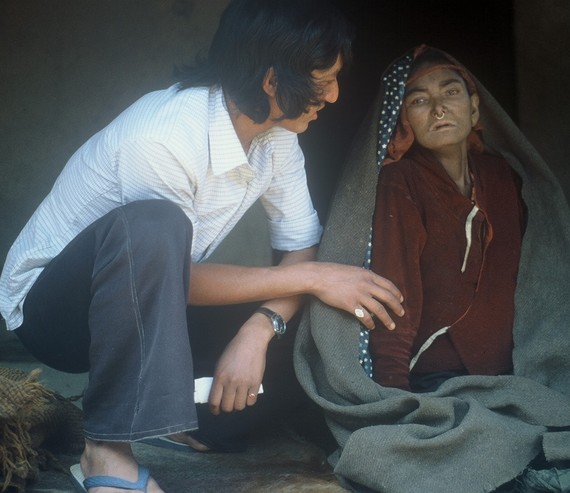

Sailendra Shrestha, Gumda health worker, with a patient (Mercer)

Sailendra asked if I would like to make home visits with him to see some of his sicker patients, and I readily agreed.

We set out the following morning to find a two-year-old boy whom Sailendra feared had pneumonia as a complication of measles. As we drew near the house, I began to hear eerie howling sounds echo down the trail toward us, growing louder as we approached. I turned to Sailendra with a questioning look, and he turned to me with an expression that I will never forget.

"Oh no. We are too late," he said softly. We were hearing the distinctive wail made by women when someone died. More than just a death: in this case the death of a child who might have been saved with a few doses of penicillin. But health post supplies of that drug, like many others, had been depleted several weeks before. The child's parents could not afford the expense of the full day's walk to the nearest store where drugs were available.

We moved into the shadows of the house and stepped inside, where I could see the boy's grandmother sitting on a mat and holding the lifeless body of a small child, white and still, in her arms. She was half-singing, half-crying an ancient sound of mourning, rocking him gently and fondling his face, arms, and legs. It was a painful sight, almost too difficult to witness.

We expressed our condolences and stepped back out of the house.

"This is the hardest for me," Sailendra told me as we started back down the path. "I could do so much more if I had more medicines, or if I had a microscope for diagnoses. All the supplies we get run out long before they should. And no one in Kathmandu even remembers that we're here; we're too far away."

As Sailendra lamented those years ago, Gumda had been mostly forgotten by the central government. Although improvements have been made in the health system since then, I've wondered how much has changed there. Seasonal roads were built into the district after I left, but they are still several hours away on steep trails. Many other villages in Gorkha are also inaccessible except on foot. Each new picture of the flattened houses, anguished women, and stricken men brought back the question: how will they get through this? They've lost homes, loved ones, animals that were their livelihoods, all at once. The monsoon rains are starting. Even before this disaster, their lives were too often at the mercy of weather, chance, and the will of the gods.

The needs are overwhelming, and, sadly, international aid is already falling far short of what was pledged. All most of us can do for the moment is contribute funds, and try to choose organizations that will use them well. While I'm not in direct contact with any of the aid groups working there, I know Oxfam America as a very reputable group, and they have been able to get food and tarps for shelter into northern Gorkha. The America Nepal Medical Foundation, based in the U.S., is very active and has many local partners. The best sources of help are usually organizations that were well established before the earthquakes.

Serious reconstruction will be needed when the immediate relief efforts are completed. Doing it right will be important. The Nepali people are remarkably resilient and resourceful; they will rebuild. But right now they desperately need help to get them to that stage.