Like never before, 2016 voters tell pollsters how much they dislike the major political parties and their presidential candidates. Will these voters support a third-party candidate? Voters routinely tell pollsters this too, yet it rarely works out that way in November. But one classic work of political science tells us which voters are really open to independent candidates, and how pollsters can gauge this support in real-time.

Pundits speculate about independent presidential candidates in every cycle, but this year the discussion is all the more earnest. Both former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg's short flirtation with a candidacy, and discussion in the #NeverTrump movement about a possible conservative third-party challenge, are symptoms.

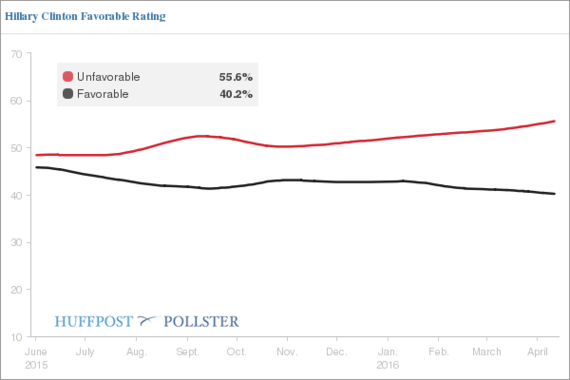

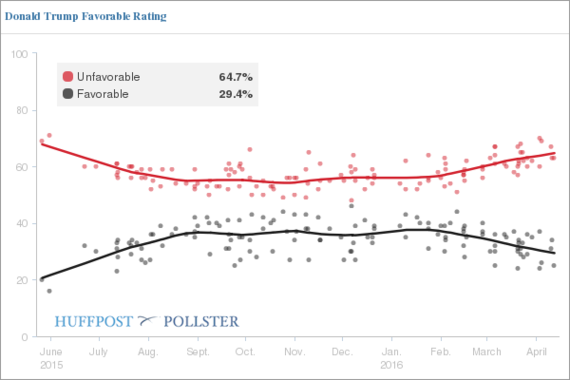

Underlying all this talk is the fact that both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump would be fairly unpopular presidential nominees. Both candidates have unfavorables well above 50%. In February, I examined Donald Trump's record-high unfavorables and what they mean for November.

How Pollsters Ask Third-Party Support, And Why It Doesn't Work

Pollsters regularly ask about third-party support, often in one of two ways.

One way is to ask voters if they'd support a third-party candidate in some kind of yes-no question. Some exit polls in the Republican primaries did this and, in Florida, half (54%) of primary voters said they'd consider a third-party candidate.

Another way is to add the third-party candidate to the general-election horse race question. A February USA Today poll found that a Bloomberg candidacy would draw support from Bernie Sanders and give Donald Trump a plurality of the popular vote.

Pollsters know that both these question styles aren't very predictive. As Natalie Jackson mentioned, most voters support their parties' nominee in November in any case.

But there is a way to accurately gauge potential third-party support using survey research. The answer comes from one of the classic works of 1980's political science.

Rosenstone's Four-Part Test for Third-Party Support

University of Minnesota political scientist Steven Rosenstone and his colleagues first published Third Parties in America in 1984, using hard data to examine every third-party presidential candidacy from 1840 onwards. A second edition was published in 1996 to update the work for Ross Perot's 1992 candidacy, and the work remains the book on third-party voting.

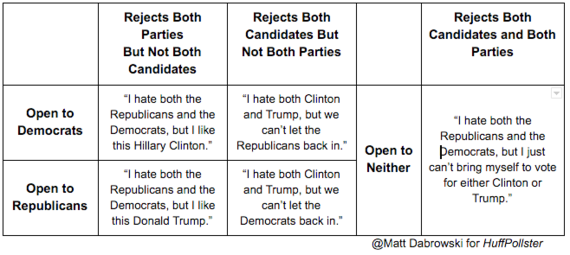

Among his many insights, Rosenstone sets up a four-part test for the accurate measure of third-party support. A potential third-party voter must reject both the Republicans and Democrats (1,2) and both the Republican and Democrat nominees (3,4). In effect, voters have to say 'no' four times before they're truly open to stepping outside the two-party system, making this a four-part test.

Why four? Because voters understand the two-party system. Openness to one party, or to one nominee, would obviously lean the voter towards that choice and not a third-party choice.

Let's think about your stereotypical opinionated uncle. He's disgruntled by the choices in this year's elections and wants to tell you about it. Depending on how he falls on the four-part test, he could tell you something like this:

You can see that the voter is only a potential third-party supporter in the last case where the four-part test is met.

1992 met this test. On one side of the tally sheet were the Democrats' move to the center and Bill Clinton's personal scandals; on the other side were twelve years of Republican government, a weak economy and George Bush's no-new-taxes pledge. Ross Perot won 19% of the popular vote, and Bill Clinton to won the electoral college.

I've used Rosenstone's method regularly in my career as a political pollster. My clients are usually disappointed to find out that few voters met the four-part test in any given election. Usually the number is in the single digits.

Only very rarely is this not the case in a statewide race. Think of the Connecticut Senate race in 2006, and the Alaska Senate race in 2010. In both cases, the state's dominant party rejected the incumbent in favor of an unacceptable nominee, and the minority party's candidate wasn't much competition. The result was that an incumbent with good favorables was able to win as a third-party candidate.

What The Four-Part Test Looks Like In 2016

Some 2016 pollsters do ask all four fav-unfav questions. Consider the March Bloomberg Politics National Poll, which had Clinton at 38% net unfavorable, the Democratic Party at 43%, the Republican Party at 60%, and Trump at 68%.

So even if the aggregate unfavorables are high on each question, different people will obviously dislike political actors for different reasons. Republicans will be unfavorable to Democrats but not to their own candidates, and vice versa.

I asked the venerable Ann Selzer, who runs the Bloomberg poll, what she thought. Her surveys regularly ask all four fav-unfavs. "It's way smaller when we use 'and' to combine across four questions. People dislike different things," Selzer said.

What Happens Between Now and November

This potential pool of third-party support will wax and wane with the nominees' favorables. And the odds are that disgruntled primary voters today will become loyal partisans in November. As I mentioned in February, party members have a strong interest in building support for their nominee regardless of who it is, and even unpopular nominees can see their favorables rise significantly during the general-election campaign.

That makes Rosenstone's four-part test -- the most accurate way to poll third-party support -- a metric to watch for the rest of the campaign.