Forests are a huge potential source of wealth and opportunity. Governed wisely, they support livelihoods, promote food security, generate export earnings and nurture vital ecological systems. That is why "sustainably managing forests" is part of the 15 Sustainable Development Goal -- the "land use goal" -- which the UN General Assembly is expected to adopt this month.

A new approach to managing the forests of Liberia -- where I was born -- is providing a useful example of the innovative thinking that is needed. If successful, it could contribute significantly to the achievement of SDG 15 worldwide.

In many regions of the world, forests continue to be plundered, consolidating the power and personal fortunes of ruling elites and enriching foreign traders. Across the Amazon, the Congo basin and many parts of Southeast Asia, rainforests have been stripped out at a dizzying rate to line the pockets of foreign logging companies and their supporters in government.

In Africa, too, forest communities -- often among a nation's poorest -- are robbed persistently of the resources they rely on for life and livelihood.

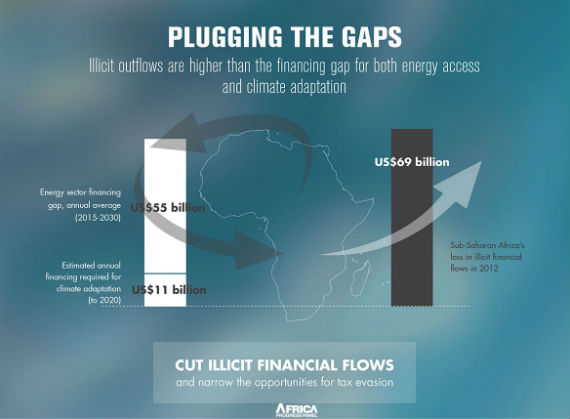

View a larger version of this graphic here.

Graphic by the Africa Progress Panel

Kofi Annan's Africa Progress Panel has long advocated for Africa's natural wealth to be better managed so that it drives dynamic and inclusive growth. While its 2013 report looked at the issue of Equity in Extractives, its 2014 report, Grain, Fish, Money, highlighted the paradox of poverty amid plenty in the forestry sector, focusing on the forests of West and Central Africa.

The report found that African governments are failing to protect valuable national forests (and fisheries). Powerful vested interests, domestic and foreign, are essentially being "licensed to plunder." At the same time, the wider international community has failed to develop the multilateral rules needed to effectively govern global markets.

International cooperation on stopping the plunder of resource assets has been weak: countries have failed to coordinate legislative changes that would limit the extensive opportunities available for illegal practices. And authorities in Africa often lack the technological, financial and wider capabilities needed to manage forestry, fisheries and other resources, and to prevent tax evasion.

As commercial pressure to exploit Africa's forests mounts, the Africa Progress Panel therefore called for an urgent rethink of approaches to sustainable-resource management and strengthened regulation.

One such bold new approach is signaled by the recent $150m (£96m) forest-protection deal between Liberia and Norway. The deal aims to shift Liberia's forest economy from a model of extraction to one of protection, and to make forest communities the beneficiaries.

Liberia has an area of forest the size of Denmark, which for years was a cash cow for a handful of people. As the UN security council has highlighted, during the country's 14 years of civil war, the illicit sale of Liberian timber on international markets was a major source of funding for the warring factions, including that of former president Charles Taylor.

When President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf took office in 2006, she promised a new era in forest management. She pledged to tackle corruption in the forestry sector, cancelled all logging concessions and started with a clean slate.

But what played out in Liberia was typical of the sector worldwide. The country's forests remained at the behest of industrial-scale, export-based logging, and profit through elite capture and extraction remained the norm. Permits intended to benefit small-scale landholders were abused by large logging companies that ignored laws and dodged taxes. Income from the sector fell dramatically short of expectations, delivering just about 6 percent of an official estimate between 2012 and 2013.

The Liberia-Norway deal is an opportunity for a fresh start. The Norwegian government has pledged $150m up to the year 2020 if Liberia keeps its forests standing -- putting communities in charge of conserving their forests, and keeping industry out.

Norway's minister of climate and environment, Tine Sundtoft, called this commitment "brave and farsighted," with Liberia choosing "a sustainable approach to development."

With Liberia still reeling from the impact of the Ebola crisis, "avoided deforestation" payments can help the nation to rebuild along a new development course, bolstering local capacity to protect forests, concentrating income gains among the poor, and averting the huge social and environmental fallout of large-scale logging.

As Saah David of Liberia's forest authority says: "The deal with Norway creates the economic space in which we can support government revenue while exploring new, community based approaches to forest management which generate livelihoods but represent a shift away from traditional industrial-scale logging."

In October, Liberia's forest authority is sponsoring an international conference in Monrovia on rethinking Liberia's forests, where several issues will be explored. These include looking at how a proper economic assessment can be made, for example, of the non-cash bounty of the forest, including the food, medicine, shelter and spiritual sustenance it provides.

The payoffs will be felt internationally, too. At this year's Paris climate conference, the world is set to agree to a deal to stay on the right side of the danger line on climate change. Forests will be integral -- as a resource not to extract but to be kept alive and nurtured as a key sink for carbon emissions.

Such questions go to the heart of the "paradox of plenty" -- that the natural wealth of many emerging economies is being chopped down, mined or pumped, to line the pockets of a privileged few at the expense of the global poor.

Thankfully, Liberia is now wising up to the short-termism and devastation of the old "development" path. If the country gets its forestry transformation right this time, it could inform and enable locally controlled forest management on a global scale.

This post is part of a series produced by The Huffington Post, "What's Working: Sustainable Development Goals," in conjunction with the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The proposed set of milestones will be the subject of discussion at the UN General Assembly meeting on Sept. 25-27, 2015 in New York. The goals, which will replace the UN's Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015), cover 17 key areas of development -- including poverty, hunger, health, education, and gender equality, among many others. As part of The Huffington Post's commitment to solutions-oriented journalism, this What's Working SDG blog series will focus on one goal every weekday in September. This post addresses Goal 15.