It's part of Mormon theology that God's purpose in sending His children here to earth is the "immortality and eternal life of man." He intends for us to learn and grow, and that was only possible in a situation separated from Him, and in a mortal body, which enables us to experience pain, and in a mortal world where we would be forced to deal with limited time. In fact, Mormon missionaries call this "The Plan of Happiness." I love this part of Mormon theology, that we are not being punished for the sins of Adam and Eve in the Garden, that God doesn't have some grand design that is His own and has little to do with us. We aren't here only to give praise to God. In fact, on some level, God exists for us, and not we for Him.

As a parent myself, I find this makes a lot of sense to me. I want what is best for my children in the long-term. But the reality of this in day-to-day living doesn't always make them want to jump up and down and sing praises to my name. I make them do chores. I make them do their homework. I chastise them for hurting each other's feelings or for causing physical pain. I sometimes refuse to buy them something in the moment so they can save up for it. And there are a lot of times when I am tempted to "fix" things for them and know that I can't, and that to do so would be to refuse them the chance to learn and grown and experience the joy of being independent, competent adults. Likewise, God cannot step into save us from our own stupidity and He cannot protect us from pain if He is to be a good parent.

And yet...

Recently, in a church meeting, a speaker got up and insisted that we all "choose to be happy" or "choose to be unhappy." And I became very anxious and upset about the way he talked about these choices. It is one thing to speak about the choice to be happy under difficult circumstances if you have been through those circumstances yourself. It is another to blithely preach happiness to those who have been through some of the worst tragedies that life has to offer. While I believe that God wants us to be happy, I am not convinced that this is meant to be taken as pressure to always keep a happy face on, no matter what your real circumstances. I am also not convinced that this means that feeling sad or depressed or broken are things that God would consider to be sins.

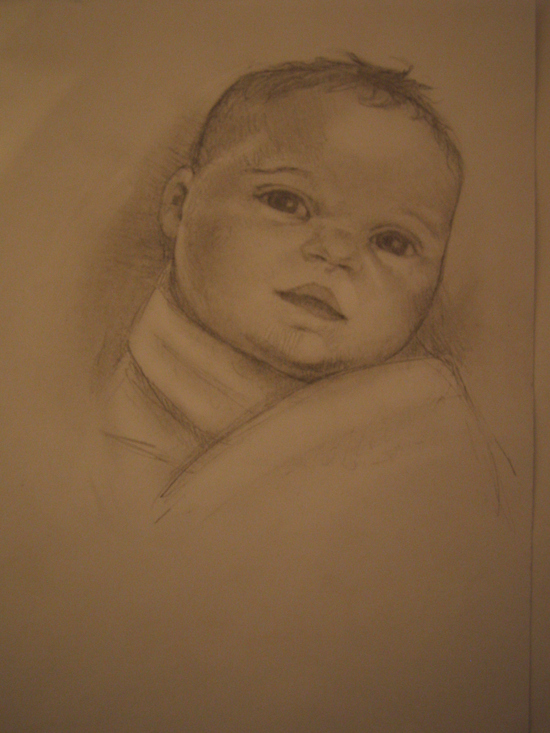

I spent many years deeply depressed after the death of my infant daughter in 2005. During that time, I found church meetings to be very difficult because of what felt like a brief window of time that I was "allowed" to be sad (about two weeks, it seemed to me). After that, I felt I was expected to go back to who I had been before, to continue in church service, and to agree to the narrative that my daughter's death had been "part of God's plan," and that I was "learning and growing" because of that "trial in my life." I found this so deeply hurtful that I stopped believing in God, but I found it very difficult to articulate why I was unable to "accept" the "lesson" that my daughter's death was supposed to each me.

My experience is a personal and specific one, but I think that many, many religious people have been through events of different kinds that have led them to a crisis of faith for whatever reason, and I suspect that I can speak for at least some of us about what goes wrong in the process. For one thing, it is important for people who have not experienced depression to either get some very serious tutoring on the subject or not to speak as if they know what it is like when they don't. If you think that staying up beat is a matter of turning on good tunes and telling a few jokes with friends, you haven't been depressed.

More importantly, if you put pressure on people who are depressed to simply stop it, as if snapping their fingers will help, you are likely going to cause them to fall into a deeper depression and feel further cut off from the faith. You will make them feel that they can no longer trust those of their religion to listen and be sympathetic. Furthermore, you will make them feel that even the fact of being depressed is something to be ashamed of, which can increase the depression and amplify it.

Ultimately, feeling sad isn't a sin. It is a normal human experience, as much as cutting your finger and feeling physical pain is normal. Trying to pretend you are not feeling pain while you are feeling pain doesn't seem to me to be particularly honorable or spiritual. While I suppose that shouting at people who are not to blame isn't helpful, either, and self-destructive behavior is to be avoided, it's not helpful to blame the victim. Even if you cut yourself with a knife, once the wound is there, it doesn't matter who created it. Surely, it only matters how to sew it up. And saying you should ignore the wound isn't going to heal it.

Looking back, I wish that people had spent more time trying to figure out how to mourn with me, rather than tell me that I should be happy. Christians are told that we are to mourn with those who are mourning and to comfort those who stand in need of comfort, but it felt to me that many of my encounters with other Christians turned out to be less about them comforting me and more about them trying to avoid feeling any of my real pain, and in particular about reassuring themselves that what happened to me would never happen to them.

There were people around me who were willing to mourn with me, but not very many of them. In case you are wondering, as I used to before a tragedy happened to me, saying "I'm sorry," is actually enormously healing. It is a sign you are willing to feel pain with another person rather than pressing it away with something like, "at least you had her for x amount of time," or "you'll see this person again in heaven," or even "this was God's will, so why can't you accept it and be happy again with your life as it is now?"

For three years, it was a daily problem for me not to spend all day wishing I was dead, and not spending several hours of that time thinking about how to kill myself. Telling me to be happy that I wasn't worse off, that I hadn't lost more of my children, or that I was physically healthy and possibly able to have another child, did not help. Being unhappy was part of the process I was going through, and I resist to this day the narrative that because I learned something from this event, I must therefore be grateful that it happened to me. I will never be grateful that my daughter died. I would still give my own life if I could have the assurance she would live and have a full life of her own. That is, in my opinion, what every parent must surely say. It is the task of parenting to put yourself between your child and the dangers of the world. And the worst moment of any parent's life is when you must confront the reality that you cannot always buy your child's life with your own.

I did not choose to be unhappy, but there were moments when I was happy and I felt guilty about it. It was useful when people told me that I was still *allowed* to be happy, that because my daughter had died, I didn't have to be in mourning for every moment of the rest of my life. It was also helpful when people allowed me to be angry at God without remonstrating with me. What I have discovered since then is that God won't be angry back. God is so immense, so full of love, that my being angry at Him doesn't touch Him. It didn't ruin my relationship with Him. Of all the people in my life I could have chosen to be angry at, He was probably the best one. He could take everything I could throw at Him and more.

I don't feel that I chose to be angry, but there were special moments when I did choose to be happy, and I think that slowly, year by year, I had more of those moments. If you haven't been in a deep depression, I think that it is difficult to speak authentically of how precious and how hard-fought those short, happy moments are. Finding happiness in the darkness I was in was something that took a strength I had never known I had before. It took practice I had never realized was necessary. It wasn't just holding onto a happy thought. It wasn't smiling and expecting that would be enough. It took courage to accept that I was never going to be the same person again, that I was never going to "get over" the loss of my daughter -- and to still hold onto moments that stood side-by-side with that grief and were made more poignant by it.

I choose happiness and I choose sadness. I choose them together and refuse to accept that my life will ever be any different. In The Book of Mormon, there is a scripture that talks about the importance of "opposition in all things." Righteousness cannot exist without its opposite, wickedness. Life has no meaning without death. We must experience misery in order to understand holiness. So I have come to accept that God's "Plan of Happiness" is also a plan that includes pain. I don't know why my daughter died. I don't think that God wanted her to die any more than I did. But this is part of the mortal life that she and I were both born into.

God wants me to be happy, but He is not interested in cheap happiness. He isn't interested in me putting a smile on my face when I'm in deep pain. He isn't interested in me being in a church where everyone pretends to be other than they are. He wants the members of His church to be in real relationships with each other, to share their true pain AND their true happiness. Because without the pain, the happiness isn't real. Real happiness -- or perhaps real joy -- doesn't come easily, but is fought for tooth and nail, hanging onto the abyss of despair, and still reaching out for the tiniest bit of light that we hope for above us.

***

If you -- or someone you know -- need help, please call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. If you are outside of the U.S., please visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention for a database of international resources.

Also on HuffPost: