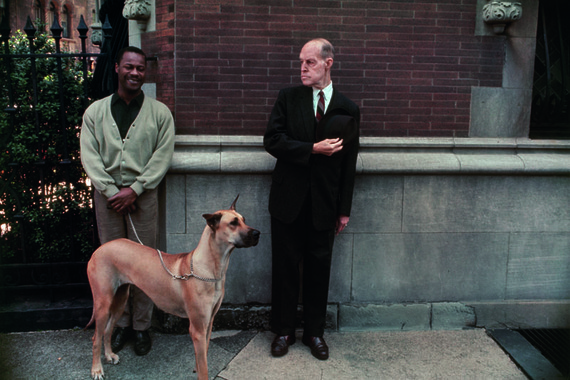

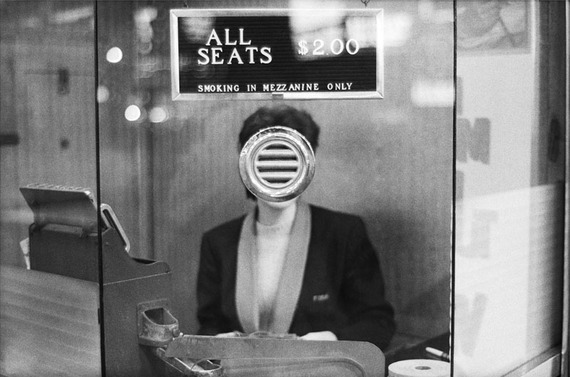

Joel Meyerowitz requires little introduction. He is a living legend in street photography. Beginning with his pioneering of color street photography, more accurately color photography in general, Meyerowitz has innovated and trail blazed his way through five decades of making photographs. For a few years now Joel and I have corresponded, mostly me nagging him about opinions on my work, which he graciously entertains albeit with moments of harsh criticism. However, I do want to say that it was Joel who offered up, albeit most likely inadvertently, the title for my first book - The Human Fragment. Despite our aesthetic differences, I've always maintained an immense respect for Joel Meyerowitz and what he's done for the world of photography.

For a long time color photography didn't interest me too much; I am a black and white kind of guy. Lately though, given my project involving disposable cameras and my Harinezumi color work, which ended up being a full-length book, color has really come crashing in on my creative life. Given this, I revisited the work of Joel Meyerowitz and came to really appreciate his brand of genius. So I got in touch with Joel, once again, and we hashed out an interview. Here's that conversation:

Michael: Joel, you began shooting color at a time when color film was perceived as amateur. Have you ever regretted this? Do you think color, in some way, helped you to express your inner self in a way which monochrome would have perhaps stifled? Color is very emotive after all.

Joel: I have never regretted my beginnings in color. In fact by starting that way I was actually freeing myself from conventions, which of course, due to my own innocence, I didn't really know existed. So color was a basic force in my development and I learned, early on, that it had an emotive power that needed to be recognized and which made me become a kind of early missionary for color.

Michael: Digital has kind of changed it all in a way. At least you don't have to commit to a roll of film. You can shoot one image in color and another in BW, or you can always change images in post. If you were doing it all over again today, digitally, do you think you would still take a similar path in terms of color and black and white, or would things be more mixed? Why?

Joel: This question has a difficult hypothesis coming as it does 15 years into the digital photo revolution. The struggles of the 1960's were unique to its time and produced the arguments and challenges of that period. Now that color is the dominant voice of photography, people are free to move fluidly between B&W and color depending on the subject, or their feelings about a particular moment, so that anyone coming into it today has a wider vocabulary to work from. But from where I stand now color would still be my way of relating to the world around me.

Michael: You speak of "feeling a photo in your gut". How often do you "feel" a photograph rather than "see" one? Or, are they one in the same for you?

Joel: As I have gotten older I find myself more committed to that gut sensation rather than the purely 'optical' point of view, which is absolutely a valid and valuable way of working. It's just that I have found that there is a direct connection between my deepest instinct - what I 'feel internally' - even before seeing the frame fill up with the image. That quickening of the intuitive 'knowing' is my guide. Maybe working for so long has trained me to trust that, and so I follow that method.

Michael: You've often photographed women. Why do you think this is, aside from the close relationship you had with your mother? Is there something else about a woman that has consistently attracted your lens?

Joel: To be honest it's not what attracts my lens, but what it is that being a man who loves women is attracted by. And it's not always physical beauty that calls first, more likely it's the enormous mystery that women are to all men, and from that mystery of the 'other' comes the urge to know something about women that the camera seems to be capable of revealing, or at least I tell myself that something will be learned about women by photographing them, and then reading the photograph. We are all such mysteries to each other no matter what sex we are.

Michael: You've often said that you've reinvented yourself, so to speak, many times over your career. You speak of this cycle and that these changes were about every 6-7 years. You seem to have really embraced this approach, this process. Yet, on the other hand, I often hear photographers - and artists alike - speak of a crisis when they attempt a change in their style or their approach. What enabled you to embrace these changes with such open arms and subsequent success?

Joel: These changes came to me, not me to them from an a priori decision to change. It just works that way when essential questions about the medium come up; like; what is the difference between color and b&w, or, if I change to the large format what will I need to let go of, or, can I give up the 'incident,' which has been the mainstay of my street photography, for a more allover look to the frame, etc? Because these questions arose from within the medium and brought themselves to my attention, they seemed necessary to embrace, and so I did, without looking back. And it was these kinds of free responses that have carried me along through all the various fields of this amazing medium. I could not live with myself and do the same repetitive stuff for 50 years.

Michael: Have you ever been concerned with losing your fans and followers by making such drastic changes in your work? I'm thinking of going from 35mm street photography to the large format Cape Light stuff. One imagines little overlap in the audience.

Joel: To be perfectly honest, I have never felt that those who might be interested in me would care one way or the other. Yet all artists have to be on guard and not listen to their audience, or even supportive critics, too much, because those outside voices cannot see what the artist is considering next, and often, when artists try to please the crowd, their work flattens out. I know that with artists, film directors, and musicians I admire, I am always curious to see what risks they might take, what leaps into the unknowns of their medium might be on their minds. And I am heartened when I see them step into a risky new place.

Michael: What makes a New York City street photographer up and leave the sidewalk to photograph these almost perfect in their beauty seaside images - also devoid of the human element?

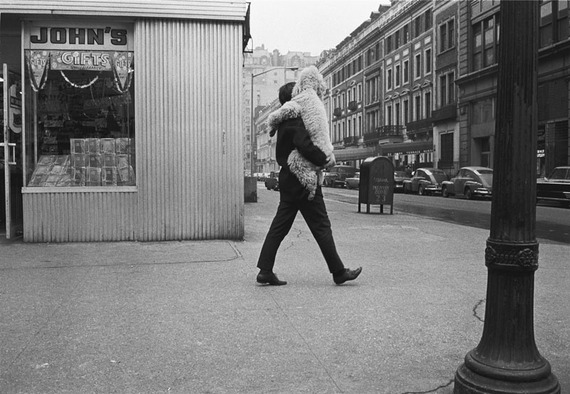

Joel: When I made the leap into the large format I had no idea that landscapes, or light, or portraits, or architecture, would be future subjects. My reason was quite simple actually. Once I changed to color full time I had to step back 15 feet or so from the plane I normally worked on when shooting on Fifth Avenue. That change - made to give color's shallow depth of field more room to describe the entire space - caused me to reconsider what to make the frame about, and it was then that I gave up the 'incident,' long the basic way of working for street photographers. You know what I mean; 'the great catch' way of making images; the kiss, the clench, the hug and handshake, the darting look, and all the grace notes we have come to expect from street photography. I saw that by stepping back and taking in the overall image that I would need to make bigger prints with more 'description,' which, after all, is what photography does first; describe things. This led me to the 8x10 inch view camera with a film of such quality that it would easily let me go up to 60 inches or more in print size. In fact, in 1976, 2 weeks after I first began shooting on Cape Cod, I raced back to New York to process and print, and when I saw the first frames I immediately took some of them to a lab and made a few 40 inch prints and brought them right from the lab to John Szarkowski, head of MoMA's photo department, because no one was making large color prints then, and I wanted to share my thoughts with him about what was now possible.

Michael: I've heard you speak of trying to avoid "shooting the arrow" into the center of the photograph. That is, you have placed the subject, and often subjects (multiple) of your photographs away from the center. In fact, in most of your street photographs the eye wanders across the frame as if reading a book from left to right - a story, so to speak. Do you think this is what begins to separate a snapshot from a photograph?

Joel: I have always felt that a photograph was 'made,' not merely taken, if you know what I mean. Making means that the artist has a degree of consciousness of what is going on that is greater than a snapshot requires. And it is from consciousness that 'seeing' begins to develop over the whole of the frame and that means 'timing,' too. To put it simply, consciousness, along with intuition, is what separates artists from snap-shooters. I am not demeaning the snapshot, since we have all seen great good fortune come from those often brilliant instants, but to be consistent as an artist requires another level of thinking and discipline

Michael: Given all the digital technology available to the photographer today, we see photographs being produced as much in post-process, as at the time of capture. Photographers manipulate their work more and more, and often chose the image from a selection of dozens that were captured in burst mode. How does all of this affect the integrity of the photographic image, or does it?

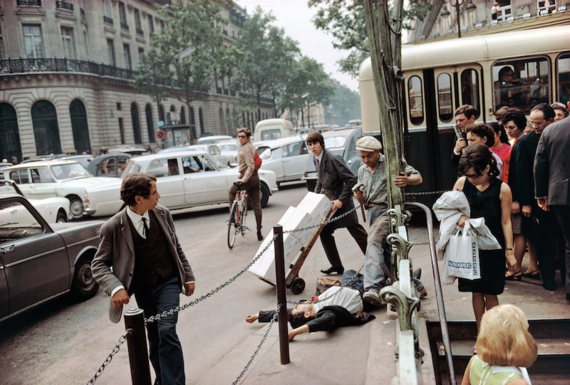

Joel: Trusting what one sees in a photograph has become a dilemma for everyone now. And with these changes you mention comes a basic distrust of the visual record as the physical truth of the moment. Some years ago, in the early days of digital, I had a show of vintage 35mm works at an uptown gallery in New York City. All of the photographs were made 20 or more years earlier and contained many startling 'moments' that I was quick enough to see and photograph - speed and instant perception being the standards for my generation. Yet, when visitors to the gallery saw these images, I could hear them say, on a number of occasions when I was in the gallery, 'this must have been set up, or directed.' They could not imagine that someone could be quick enough to see things and actually get them! So they assumed that they were fakes. How much the world has already been changed by the digital revolution would astonish someone like Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Michael: When 9/11 occurred you seemed to intuitively go to your camera. How did photography help you cope with what must have been a very traumatic time for someone so physically close?

Joel: As a native New Yorker I wanted to be of help, and it turned out that making the historic record was my key to entering the off-limits zone of Ground Zero. By becoming the 'eye' of the place I saw everything that was there, as well as all the human effort to find and identify the dead. Working in Ground Zero changed my life in many ways, but as an artist it showed me that my work could shift from being self involved, as most artist's works are, to becoming more socially useful.

Michael: Joel, before we leave off, might you offer your thoughts on the future of street photography? The digital age has given rise to a very pervasive visual culture and both the idea of the photograph and the photographer has changed considerably in your lifetime. Where are we headed?

Joel: Who can predict anything, Michael? However, I do have a sense that the freedom of digital - the fact that anyone with a smartphone has a camera - will invite millions of fresh minds into considering making photographs. People who might never have bought a camera have been given one, and since they are carrying it they use it in strange and unexpected ways. It is from this vast new pool of people without a photographic education that new visions will emerge. This gives me hope.

Michael: Joel, thank you kindly for your time and for this wonderful chat. You've been a big influence on me and I deeply appreciate both your work and your kindness.

Joel: It's been great talking with you, Michael, you always ask provocative and timely questions.

Joel Meyerowitz is an award-winning street photographer with a career spanning more than 50 years. He was instrumental in changing the attitude toward color photography from one of resistance to nearly universal acceptance. His first book, Cape Light, is considered a classic work of color photography and has sold over 120,000 copies and is being republished in a new edition this fall by Aperture. His 50 year Retrospective book, Taking My Time, published by Phaidon, is now out and is accompanying a large traveling exhibition touring Europe this year.

Michael Ernest Sweet is a New York-based Canadian photographer and writer. He is the author of two street photography monographs, The Human Fragment and Michael Sweet's Coney Island both from Brooklyn Arts Press. Michael interviews artists and reviews books here on the blog. Use this form to contact Michael with suggestions for future features or reviews.