I've stated repeatedly that a massive amount of stimulus has been required to generate GDP growth of just 2.0%-2.5% annually since the end of the Great Recession (June 2009). We have further said that the removal or reversal of some of these stimulants will be a tough hurdle for the economy to overcome. We therefore believe that we will remain stuck in an extended period of sub-par growth - a period characterized by Bill Gross as the "new normal." But while Gross blamed "deleveraging, deglobalization, and reregulation" for the sub-par growth in his September 2009 Investment Outlook, we place much of the blame on a Fed that opted for several years of slow growth rather than a shorter but more painful period of adjustment. Those same Fed decisions are likely to result in an extended period of sub-par asset returns as well. Said another way, we have borrowed growth and prosperity from the future, and on a massive scale.

The most obvious example of the stimulants referred to above has been the Fed's suppression of both short- and long-term interest rates. The Fed's initial response to the financial crisis, drastically reducing the Fed Funds rate (the rate at which banks lend to each other overnight), was a normal and expected policy response to an economic downturn. Lower interest rates, at least in theory, should have helped support an economic recovery through increased consumer spending and more robust business investment. But while lower short-term interest rates did have a modestly positive effect, the benefits were not enough to offset the massive damage that had been done. As a consequence, the Fed became more aggressive in its monetary easing and implemented "Quantitative Easing", or the large-scale purchase of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

One unique characteristic of the Great Recession was that it was caused, at least in part, by a bubble in residential real estate. As such, the Fed found it of utmost importance, perhaps understandably, to use monetary policy to support the housing sector. This was the genesis of "Quantitative Easing". Long-term interest rates were not coming down fast enough to increase housing affordability, so the Fed went to great lengths to reduce long-term interest rates and therefore increase housing affordability and stabilize housing prices. Gradually, over a period of 2-3 years, housing prices did stabilize, and housing construction and turnover also started to improve. But for the Fed, this still wasn't enough. Unemployment was still too high and lending standards remained too tight to drive acceptable economic growth. And so the next phase of the Fed action began: the deliberate inflation of asset prices. In our view, this is where the Fed overstepped its mandates.

In lowering long-term interest rates, Ben Bernanke explicitly stated that one of his policy goals was to boost stock prices. The rationale was that if people felt richer, they would spend more. Economists call this the "Wealth Effect." But Bernanke overlooked one key point. Those hurt most by the economy's downfall did not own stocks and therefore received no economic benefit from stock appreciation. Therefore, a more accurate characterization of Bernanke's initiatives to boost stock prices would be "trickle-down economics" - a theory accurately described by Wikipedia thusly: "economic benefits provided to businesses and upper income levels will indirectly benefit poorer members of society when the resources inevitably "trickle down" to them." But while the first part of the initiative went according to plan (stock, bond, and housing prices have soared and the rich have gotten much, much richer), the effects on the middle class have been much more ambiguous.

Why are we talking about this now? Because a sea change has taken place that not many people are talking about. Following years of highly successful efforts to boost stock prices, the Fed has come out and explicitly said it thinks stock prices are frothy. Specifically, on May 6 Janet Yellen said: "I would highlight that equity market valuations at this point generally are quite high." And while Yellen did make comments in July of last year that valuations for social media, biotech and small-cap stocks look stretched, this new warning is far more encompassing. I mean, who doesn't know that biotech and social media stock prices are outrageous? I'm just sayin'.

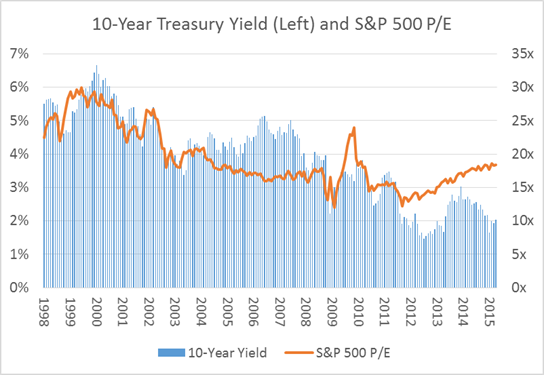

The table below shows that the P/E on the S&P 500 topped out at about 30x in mid-1999. The current level is about 18.8x. On the surface, this would seem to suggest that there is a lot more room on the upside. Recall that Alan Greenspan made his famous "irrational exuberance" comment on December 5, 1996 - a day on which the S&P 500 closed at about 744. The index proceeded to appreciate another 105% to a peak of about 1,527 in March, 2000. We are drawing this parallel because current Fed Chair Yellen has already made cautionary remarks about the level of asset prices, to include stocks. The worry is this: if we rely on history as a guide, it would seem that the Fed has much more power to drive stock prices higher than it does trying to contain an overheated market. This asymmetric control should worry us.

It remains to be seen whether Yellen will be sufficiently alarmed by her inability to calm the "irrational exuberance" she perceives in the capital markets. If so, a rate hike could be coming sooner rather than later. For my part, I am not seeing the kind of "irrational exuberance" that has characterized previous market tops. In my book The Arrogance Cycle, I discuss how bull markets generally end when investors adopt a "can't lose" mentality. From where I sit, there still seems to be a lot of fear and caution by the investing public. In markets like these, the fundamentals don't matter as much as they should. However, this is not to say that stocks aren't expensive. Eventually, the fundamentals will win the day. When that day comes, we will be glad we are invested in the types of high-quality and defensive companies that characterize our current portfolio.