I'm ashamed to say initially I was left pretty much unmoved after reading excerpts from David Margolick's newest book. As usual, I was on the look-out for historical or stylistic errors. From that context, preoccupied with when bearded iris bloom and the nuance of high school fashions, past and present, I found these fragments from Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock, to be admirable enough, but nothing earth shattering.

What caused me to so totally misjudge this book? The answer, both simple and embarrassing, best takes the form of a cliche: because of the trees I failed to see the forest. In this case I'm not talking about being distracted by background details, but rather, how I failed to view two people and their actions as important beyond the specific and the particular.

Considering Mr. Margolick's book to be foremost a commemeration of the 50th anniversary of the emergence of the "Little Rock Nine", of Brown versus Board of Education fame, in my estimation it was yet another exploration of already-exhausted, semi-familiar territory from the civil rights era. This biased view alone is a powerful indictment, of even my impatience with history, indicating just how much we seek to avoid issues of race in America.

Reading Elizabeth and Hazel straight through in one sitting, David Levering Lewis, the esteemed professor of history at New York University, and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the definitive W. E. B. Du Bois biography, had no such problem.

"David Margolick's dual biography of an iconic photograph is a narrative tour de force that leaves us to grapple with a disturbing perennial--that forgiveness doesn't always follow from understanding," he wrote.

Still, even finally reading the full text, my own mistaken evaluation was not immediately apparent. Contributing to my misconception, oddly enough, was the unfolding chronicle of abusive white students and their complacently unresponsive teachers. Unsuspecting of what's to come, one is lulled along, like motorist in a highway traficjam, helpless to look away from a wreck and move on. 'What new outrage will happen next?', the reader wonders. So only gradually are the dramatic experiences of two 'ordinary' individuals, appreciated as something extraordinary, something more revelatory and more significant even than a detailed account of the nascent effort to achieve equal education in the United States.

Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan Massery are proxies for two Americas, one black and one white, one still scarred by the past, the other eager to, at last, leave the past behind; indifferent to 'yesterday's' social ills and hell-bent on preventing reverse discrimination now. Their intertwined story in Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock , is a vivid illustration of how, so many well-intentioned efforts to the contrary, fear and misunderstanding continue to trump even our common humanity. Louis Begley in concurrence insist,

"Elizabeth and Hazel is required reading for every American who wants to understand why the wounds inflicted by the heritage of slavery and Jim Crow remain unhealed."

If my experience last week is in any way typical, whites abroad might benefit from reading it as well. Conducting a tour of Harlem for a group of forty-four patrons of the Guggenheim Museum in Venice I started off at a twenty-eight storey condominium tower on Fifth Avenue at 120th Street. We visited a triplex apartment for sale for four point three million euros. Turning from admiring the view, one especially chic member of the group asked, "Why have you brought us here?" "Why? This", I explained, "is an important aspect of the Harlem of today."

Inasmuch as I had already said that the average yearly income locally was just thirty-six thousand dollars, that one out of every five New Yorkers lives in poverty, the irony was not entirely lost on her. Yet what she said next did surprise me.

"With your president, have you not put race behind you here? And Condoleezza Rice, she was one of the most powerful people in the world, was she not?" "Have Margaret Thatcher and Angela Merkel meant an end to misogyny and inequality for women, then?" I replied.

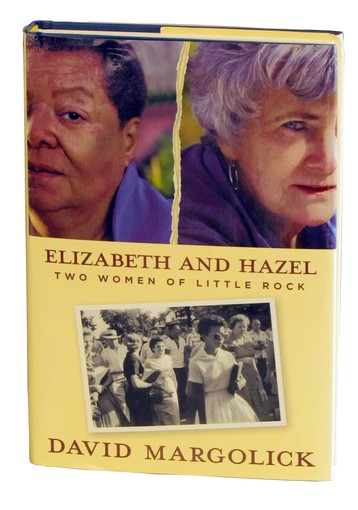

Setting the stage for his 'tour de force' straight away, Margolick introduces the stark image of racial confrontation made on September 4, 1957, by photo-journalist Will Counts. Through this haunting picture he relates the sad saga of an upright but obviously afraid Elizabeth Eckford. Immaculate in a homemade white piqué and gingham dress, she is trying to enter, and desegregate, Little Rock Central High School. Center stage, from behind, her nemesis, 'the angry white girl', Hazel Bryan, is a Greek chorus of every bigot who ever lived, shrilly screaming, 'Nigger, go away!'

The same age, the same sex, inhabitants of the same town, divided by just a few miles, the two fifteen-year-olds lead lives in completely separate and unequal worlds. Yet they are worlds within worlds, which in some ways were quite similar. So similar, in fact, are Ms. Eckford and Ms. Bryan to each other in terms of tastes and outlook, that almost before one becomes aware of what is happening, while no one much seems to be looking, the unimaginable occurs. Matured, married and the mother of two young children, Hazel Bryan Massery reaches out and apologizes to Elizabeth Eckford. She attempts to atone for a youthful indiscretion. Having a hard time overcoming the humiliation and hurt of a lifetime, in ensuing decades of great hardship, Eckford found scant comfort in Ms. Bryan Massery's gesture.

Then, forty years on after their picture was first taken together, it's taken again by Counts. Only, this time, it shows the two women smiling. They are publicly, conspicuously and repeatedly reconciled. It is a cause for celebration, that two such archetypal antagonists can come together as unlikely companions, a source of hope and inspiration for two nations intent on moving beyond our troubled history, that these two evolve into friendly confidantes.

Sadly, as Margolick relates, it only takes a few years for this fragile friendship to fall apart. Just what is it about difference, about gender, class, sexuality, nationality, faith and race that makes us so wary? Why, despite mutual interest and real shared affection, have two women, the same age, from the same town, with so much to gain from forgiveness, become so terribly re-estranged?

Is their hostility like that of South African men, who rape defenseless women to prove themselves despite relative social impotence? Or is it like Israelis, whose very nationhood is defined in part by the domination of Palestinians? With equality and friendship, would the desert not be made to bloom? Would a united populace not be better empowered to effectively combat the residual impact of apartheid, as well?

As an historian, it's tempting to view Hazel and Elizabeth's enmity in such terms. A look at American journals and periodicals of a century ago certainly helps to illuminate such a notion. Life, Century, Harpers, or the Saturday Evening Post, so far as how they portrayed 'Negros', they were alike. Whether in cartoons, advertisements, travelogues, editorials or human interest stories, it is always the same: we are buffoons, harlots, knaves, wastrels, criminals, subdued servants or child-like simpletons. How pervasive such stereotypical representations were. How reassured they must have made many people feel, whether leaders in power or the insecure masses.

Yet, even though hating and demonizing blacks as a means of group aggrandizement, was at work in 1950's Little Rock, something much subtler, and simpler too, has riven Elizabeth and Hazel apart. Put plainly, they each have come to mistrust the other.

Having had decades to reflect on what happened, Elizabeth has come to find it inexplicable and implausible that Hazel was not a member of the local hate group that had planned in advance to ambush her. After all, several members of the group had joined Hazel each weekend to dance on a local version of the American Bandstand program. Moreover, the vehemence and brutality of Hazel's assault, Elizabeth came to feel, belied a random and spontaneous act.

Elizabeth apparently feels that Hazel's kind of malevolence was the kind that Robert Kennedy talked about, after Dr. King was killed. Certainly, she feels, Hazel has hardly done enough to atone for all that.

"There is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night. This is the violence of institutions; indifference and inaction and slow decay. This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colors. This is the slow destruction of a child, by hunger, and schools without books and homes without heat in the winter."

As for Hazel, from a position of comparable privilege, poor thing, she seems totally perplexed that Elizabeth doubts her sincerity. Ordinarily, in a friendship, just as the Bible prescribes, one apologizes, asks for forgiveness, and a true friend forgives. The process is healing for both the culprit and for whomever one has hurt, it is a cathartic blessing, as opposed to an incessant prayer. For Hazel, expecting a conventional outcome, the idea that some hurts warrant a litany of mea culpas, is inconceivable.

Three times now David Margolick has looked at noteworthy episodes from black life in America with favorable results. If one regrets that more African American authors don't seem to have the same opportunities to tell our history that's so crying out to be told, nevertheless he brings to these works an invaluable detachment and objectivity. Squeamishness about even the suggestion of past injustice, make his focus on such subjects more penetrating than many black authors might have been permitted. Reading Margolick's books, one readily agrees with the author, that materialy and emotionally, his black protagonists consistently fared far worse than their adversaries.

This, too, is what makes Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock, so powerful. Most of us would be delighted if things were only different. If the issues that sparked the emotions and actions captured in Will Counts' photograph, no longer existed we would jump with joy. President Obama definitely would be pleased if our schools were now desegregated, offering a first-rate education to children nation-wide, enabling us to compete with the best and brightest anywhere. But David Margolick's new book is just the cautionary tale to remind us, we aren't there yet, that as a nation and as people, until we begin to learn greater empathy, we never will be there.