With tens of thousands dead, and scores dying or injured, what is the value of Haitian pride? The answer, to what one might understandably misconstrue as a purely rhetorical question, is that it is something that's indispensable. Haitian pride is paramount, if we are to use this most recent compounded tragedy to affect in our hemisphere's poorest country, something superior to making things merely as they were before.

Undoubtedly such sentiments were largely responsible for the rapid rebuilding of the White House, after the British burned Washington during the War of 1812, and for restoring the Summer Palaces at Tsarskoye Selo, following defeat of the Nazis by the Allies. Certainly there were critics at each place and time who felt that more pressing needs ought to be given priority. Still others dismiss such monuments as emblems of indifferent rulers' privilege and prestige.

Belying such concerns, in Communist China, several generations since the reign of the 'last emperor', as a symbol of continuity, as an emblem of national unity, one that's the focus of the country's pride, they impressively preserve an imperial palace. Even in New York, where the richest man in town happens to be the executive, disdaining an official residence for his luxurious private and more palatial house, Gracie Mansion is nonetheless well maintained.

Expressions of a community's ideals, of a nation's stubborn resistance to tyranny and injustice, are treasures of inestimable value. This is why Americans have been fixated on the notion of building a new and better World Trade Center and 9-11 memorial. It's also why, soon after the dead have been buried and a semblance of normalcy established, the world must help to rebuild Haiti's National Palace.

"As a small girl, even with the Americans still decamped, I found Haiti's National Palace to be really quite something!" said my friend

Martha Chandler Dolly. This was about 20 years ago. Martha was reminiscing about her girlhood, in Port-au-Prince: her school, run by uncharitable nuns, her uncomfortable school uniform that must be kept always immaculate, a young gay servant, who had once pleaded for a length of crêpe-de-chine and a bottle of Arpege perfume in lieu of a month's wages, and a delusional neighbor, Cora Poirot, claiming to have been the Prince of Wales' mistress in Paris before the advent of Mrs. Simpson. Madame Poirot had regaled a wide-eyed little Martha with tales of the fabulous parures of diamonds, rubies, emeralds and sapphires she'd received from his Royal Highness, tokens of ardor, she'd been forced to sale, in order to return home to her husband and their 7 children.

How these bon mots delighted me and Martha's other guests. But of all the lore and landmarks of her youth that Martha recalled, it was the gleaming white palace that loomed largest. "It is a precious symbol for everyone of how even beaten slaves can triumph!", she insisted. "As the years have passed by, bringing first one catastrophe, and then another, it is a symbol of the tenacity and resilience of the Haitian people, evidence of accomplishments that are imperative for us to remember." This said, she began on a theme that was very familiar to many of us.

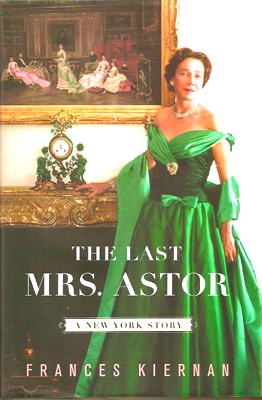

"When white American planters encountered disobedient and rambunctious slaves in the old days, they used to ship them to Haiti to be broken..." Martha maintained to me and others, even to Mrs. Astor, on several occasions, speaking of the world's first modern government run by people of African descent. "We defied the white world and defeated Napoleon, who had nearly conquered the globe. Whites despised our independence as impudence, and we have been paying for this effrontery to injured white pride ever since!"

Martha invariably continued in a mellower mood, remembering incidents whose tenderness and pathos only intensified with retelling. Speaking of her mother, for instance, who had abandoned her father and brothers to start a new life and family with a member of the occupation forces, she said,

"After she had allowed me to brush her hair and help her to dress, before she would go out in the evening, still sitting at her dressing table, my mother would sometimes read aloud to me. How I loved these moments we spent alone together. My favorite stories were fairy tales in books from Paris, with lovely illustrations by Edmund Dulac.

'You are an ugly little girl,' my white American stepfather once told me, adding, 'but, if you have just one half of the charm of your mother, you will be alright!' The National Palace was as exquisite as Sleeping Beauty's palace as depicted by Dulac! Naturally, like many Haitians, I dreamed of being rescued. But by the time I first attended dances and receptions at the palace, as a young woman, I'd realized it was necessary that I somehow devise my own rescue."

A far more privileged Mrs. Astor had taken a far longer interval to reach much the same conclusion. She and Martha met because the widowed philanthropist had decided to use funds from her foundation to restore houses in Harlem built by her husband's family as an investment more than a century earlier. A newly widowed Martha was persuaded by the Mount Morris Park Community Improvement Association to offer tea by way of thanks.

No one in the group had known that as a girl Mrs. Astor had lived in Port-au-Prince too. Roberta Brooke Russell was the only child of John H. Russell, Jr. In October 1917, he was ordered to the Republic of Haiti to command the Marine Brigade, becoming, in effect, the island's ruler. Of course Martha Dolly had already known this intelligence which became the basis of an instantaneous rapport.

Mrs. Astor broadened Martha's knowledge by relating how she had married her first husband, John Dryden Kuser, shortly after her 17th birthday. "I certainly wouldn't advise getting married that young to anyone," she'd lamented. "At the age of sixteen, you're not jelled yet. The first thing you look at, you fall in love with...that marriage, those were the worst years of my life."

Her husband, the son of the financier and conservationist Col. Anthony Rudolph Kuser and grandson of U.S. Senator John F. Dryden, later became a New Jersey Republican councilman, assemblyman, and state senator. Not fully completed until 1920 under the supervision of the Americans, the Palace didn't figure in Brooke Russell's Haitian sojourn.

Since the start of the nineteenth century, three earlier residences built to house Haiti's rulers had occupied the prominent Port-au-Prince site with its majestic backdrop of mountains. Haiti's Imperial Palace, built prior to 1850, was the principal residence of Emperor Faustin I, and his Empress, Adélina. John Bigelow, an editor at the New York Evening Post, visited the palace a decade and a half before slavery was abolished in the states and described it as

"only one story, raised a few feet from the ground...approached by four or five steps, which extend all around the edifice..."

Commenting on the interior, he first noted how, in the entrance, "The floor is white marble, the furniture in black hair-cloth and straw. On a richly carved table appeared a beautiful bronze clock, representing the arms of Haiti--namely, a palm-tree surrounded with fascines of pikes and surmounted with the Phrygian cap. The walls were decorated with two fine portraits ... One represents the celebrated French conventionist, the Abbé Grégoire, and the other the reigning Emperor of Haiti...The latter does honor to the talent of a mulatto artist, the Baron Colbert." Bigelow praised the salon adjoining the ante-chamber where receptions were held, saying it, "displayed portraits of all the great men of Haiti".

Bombarded during a rebel revolt by the captured man-of-war La Terreur, the former Imperial Palace was destroyed on December 19, 1869, bringing down the government. A hapless President Sylvain Salnave, unable to trust anyone with the national supply of ammunition, kept it not at a garrison, but in palace cellars, hence only to be killed by his own gun powder when the building's shelled walls exploded spectacularly!

Again in August 1912, the palace's replacement, built in 1881, was seriously damaged by a violent explosion that killed President Cincinnatus Leconte and several hundred of his soldiers. It all occurred almost a year to the day from his election. Disparaging the palace, which rather resembled the sort of high Victorian hotel popular at American seaside resorts, with its prominent verandah and crested roof, The National Geographic Magazine called it, "a rather ugly structure of glistening gray-white," that nonetheless contained, they conceded "some fine lofty rooms," which other sources described favorably as, "pretty and decorated à la Françoise"

With Haiti's ruling class, widely once viewing themselves black Frenchmen, it comes as little surprise that the new recently destroyed National Palace resulted from a competition among both French and Haitian architects. Indeed, only because the highly elaborate structure proposed by the first-place French winner was deemed too costly, did the commission go to a Haitian national, who had only come in second. Georges H. Baussan (1874-1958), who went on to become Haiti's leading architect, had studied abroad and graduated from le Ecole d'Architecture in Paris.

With a construction budget of $350,000, work got underway on the new palace in May 1914. No sooner had building commenced when, in 1915, a mob assassinated President Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, setting the palace ablaze. This debacle had been sufficiently worrisome for U. S. President Woodrow Wilson to send the marines to invade and occupy the tiny republic. American forces promptly took possession of the damaged and incomplete palace and skilled naval engineers oversaw its reconstruction.

In November 1919, John Dryden Kuser, Brooke Russell's wealthy first husband, revisiting Haiti, described the new, almost finished president's residence as,

"A huge structure, quite like a palace in appearance .... It is more than twice the size of our White House and is shaped like the letter E, with the three wings running back from the front. In the main hall huge columns rise to the ceiling and at each side a staircase winds up to the second floor". The palace's primary rooms, Kuser observed, including the office of the president, were tastefully appointed and about 40 feet square.

Son of a former Haitian senator, Georges H. Baussan was the father of Robert Baussan, a modernist architect who was to study under Le Corbusier, and who later became the country's Undersecretary of State for Tourism. Georges H. Baussan's palace, like his commissions for the City Hall of Port-au-Prince and Haiti's Supreme Court Building, drew on the traditions of Beaux-Arts architecture. The Hall of Justice particularly attest to the architects ability. With interior paneling of mahogany and doors and windows made of cypress, considered by many to be Port-au-Prince's second most grandiose building after the National Palace, it took less than two years to build. Expenditures, including land acquisition, construction, electrical installation, and furnishings, totaled just under $400,000.

Like contemporary works by French or American practitioners, Baussan's palace, in addition to employing the strictly rational planning stressed by Beaux-Arts training, with hierarchical axis and cross axis, also evokes historical precedent. In this respect it resembles Carolands, an immense square concrete American house with 130 rooms. Built for railway-car heiress, Harriett Pullman Caroland, it was begun the year following the start of Haiti's National Palace. Near San Francisco,

Carolands was an unusual collaboration between renowned French architect Ernst Sanson, and talented American designer Willis Polk. With domes, pavilioned facades, oval dormers and neo-classical details, in each case, at Haiti and at Hillsborough, economically and progressively

realized in reinforced concrete, as opposed to stone, both buildings are indebted to Vaux-le-Vicomte, which presaged Versailles.

Moreover, one can't help feeling that the white-painted, two-storey National Palace, its central domed section featuring an entrance portico with four Ionic columns, was meant to suggest repulsed Napoleon's Malmason as well.

Born on August 15, 1908 Georges Baussan's son, Robert Baussan died only last year, on April 22, 2009. Still studying in Paris, he married Russian artist Tamara Zekom. The couple moved back to Haiti in 1931. Tamara Baussan died in 1999.

On January 12, 2010, the National Palace was severely damaged by a magnitude 7.0 earthquake centered about 10 miles away from Port-au-Prince. While the second storey partly collapsed, along with the dormered attic floor, the palace's columned central pavilion, a section containing the principal hall and grand staircase, was entirely destroyed. President René Préval and his wife, who were in the living quarters, which was relatively unscathed, escaped unharmed.

Greatly harmed were masses of homeless Haitians from every walk of life, many of whom only narrowly escaped dying to endure painful injuries and the death or dying of their loved ones. What is it like to suffer so, to go days without a place to sleep, afraid of aftershocks, lacking water or food?

Scrutinizing, via the painless, odorless magic of media, as the Haitians' prodigious patience slowly evaporates, their outrage and frustration swelling and festering like the bloated bodies piled in the streets or Langston Hughes' raisin left neglected in the hot sun, some can already be heard uttering 'tisk tisk, those people are their own worst enemy.' Day in and out across the world, some comfortably avoid too painful issues such as race and class, satisfied to preserve the accidental advantages which were their birthright. For them, that only three percent of New York firefighters are African, American is all about relative ability, and so is the disparity of the world's richest economy, versus, so nearby, the poorest in our region.

Even if such people are happy to retain their convenient, but illogical viewpoints, unconvinced by what a Martin Luther King, a Barack Obama, a Venus Williams or a Tiger Woods can achieve given opportunity and encouragement, the time has passed for the rest of us to continue to give such attitudes credence through our failure to take positive action.

For the lesson of September 11, 2001, the lesson of the Middle East and of Haiti, is that in our much, much smaller world, every bias, every negative inaction, will surely cause some correspondingly negative action which we can no longer avoid or ignore. Reparations and other forms of justice might inspire scorn because of our widespread reluctance to accept blame and a high price tag, but inaction is neither supportable nor prudent, inasmuch as its unintended consequences will prove to be far more painful and more costly, on the day of reckoning sure to come.