A number of compelling arguments have been made recently about literary fiction, genre fiction, and how the two relate -- such as in Arthur Krystal's article in The New Yorker, and in Lev Grossman's sort-of-reply in Time Magazine.

And yet any attempt to describe, let alone define, genre fiction or literary fiction, or to distinguish one from the other, invites so many exceptions that the effort tends to fall apart. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart grappled with a similar problem in 1964, when, presiding over Jacobellis v. Ohio, he abandoned trying to define the genre of pornography and famously concluded, "I know it when I see it."

Any distinction between genre and literary fiction matters less than it once did. For this, I'm glad. My first book, a collection of short stories, is generally considered literary fiction. My second book, the novel The Three-Day Affair, is being called a thriller.

Thankfully, the tired generalizations about genre fiction being the province of stock characters and formulaic plots have eased up, as have the equally tired generalizations about literary fiction, both pro and con. (Pro: only literary fiction has graceful prose; literary fiction alone gets to the root of the "human condition." Con: literary fiction is plot-less. Literary fiction is needlessly complicated). It takes about two seconds at my bookshelf to dispel these generalizations.

Yet as human beings, we need categories; otherwise, our lives would be impossible to navigate. We categorize and sub-categorize the food we eat, the clothes we wear, the music we listen to, and just about everything else in our lives. It would be surprising if we didn't categorize our novels, too. The trouble is finding a way to do it.

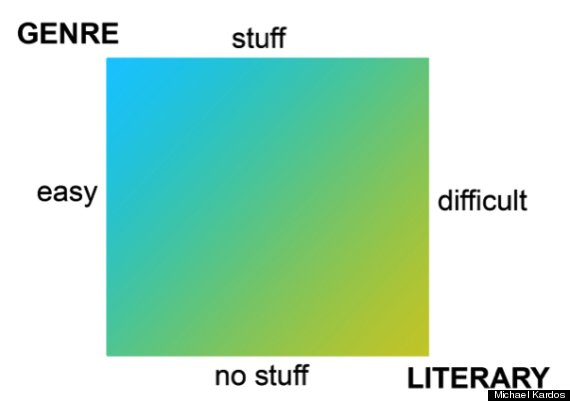

With this in mind, I offer a simple graph, meant to illustrate just how literary or how genre a work is. I call it The Literary/Genre Continuum, because "continuum" sounds cooler than "graph."

The idea is to plot a novel on the graph based on where it falls on the "stuff/no stuff" continuum and the "easy/difficult" continuum. The closer to the top-left corner, the more genre-ness the work has; the closer to the bottom-right, the more literary-ness.

By "stuff," I mean things that are out of our ordinary experience, especially things that don't actually exist (as far as we know): interplanetary space travel, elves, vampires; and, to a lesser degree, things that do exist but that are larger-than-life: serial killers; shark infestations. "Difficult" encompasses dense paragraphs, complex sentences, ambiguity, intellectual complexity, and passages that require re-reading not because they're unclear but because they're, well, difficult.

"Stuff" and "difficult" are, of course, subjective -- but not completely so. Even if you happen to speed through a Faulkner novel, you still know it's difficult. "Stuff" is a bit more objective: Vampires are stuff. A detective tracking down a murderer is more "stuff" than one investigating a robbery, but less than one hunting a serial killer -- especially if the serial killer used to be CIA.

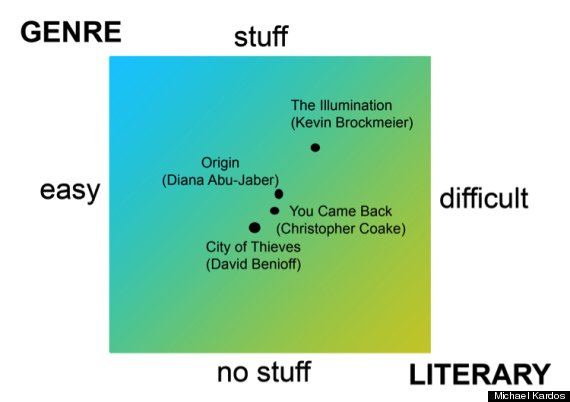

Okay. Here are a few well-known novels with my plotting:

Notably, the Literary/Genre Continuum isn't prioritizing "literary" above "genre" or vice versa, nor is it quantifying how good a particular work is or isn't. Rather, it's a way to illustrate how much literary-ness and genre-ness are in a particular work.

In graphing some novels I've enjoyed recently, I've discovered that I seem to be drawn to works that sit close to the middle of the continuum.

I know I'm not alone. There's something exciting about works that try to have it all: enough "stuff" to intrigue us without dominating the story, and enough difficulty to demand something of the reader without deterring our escape into the fictional world.

I'm not exactly sure what's next on my reading list -- but I'll know it when I see it.

Michael Kardos is the author of The Three-Day Affair.