It's not every day that a journalist becomes part of a work of art. In a stroke of autobiographical fervor a few years ago Christian Boltanski had sold the rights to his daily life to a wealthy collector, who installed 24/7 live cameras all over his studio at the southern edge of Paris. These tapes become part of a massive unfolding record entitled simply The Life of C.B. Enter one unsuspecting American journalist prepared to shoot an interview there... A French TV crew had just been chastised by the artist for trying to glamorize him with their multi-camera shoot, and he was in ill temper before we began. But he soon became both reflective and jolly, his rueful sense of humor occasionally igniting like a firecracker.

Chance installation at the French Pavilion, 2011 Venice Art Biennale

Boltanski is acknowledged to be France's most important living artist. His dark and prodigious body of work is esteemed by critics and crowds alike, and it seemed high time, at 66, that he represented France at the Venice Biennale. For the task of filling the French pavilion this year, he created an overwhelming jungle-gym of metal pipe and literally streaming video (whizzing through the vast structure as a giant ribbon of black-and-white frames). The images are of day-old infants, photos cut from Polish newspapers that announce births routinely. Every 10 minutes or so, a bell rings and the frames halt, randomly focusing on a single baby. It's a loud, visceral and claustrophobic encounter with Boltanski's most recent meditation on long-time fascinations: chance and identity. Chance is both scary and exhilarating.

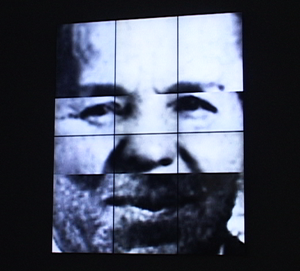

He's created a colossal machine that's a demonic hybrid of printing press and film projector. As architecture, it made me think of Piranesi, a kind of enveloping prison. It exalts the mechanical, by alluding to the Industrial Age, and satirizes it with a whiff of Chaplin's Modern Times. Chance is interactive: In the chamber just beyond the main hall is a screen that visitors can control with a big button at the entry. Faces sliced into three segments jumpcut at high speed, such that the recombinant photos whirl like a giant slot machine. Or cards being shuffled. Games of chance. Winning and losing. But the work never veers far from the assertion that we all lose in the end... Is Boltanski a pessimist? He'll say not really, that in fact he's happier than ever knowing that the world will go on without him. Nor is he a fatalist. To him, nothing is written so fate is an illusion.

Chance gives us a powerful sense of the sheer density of the human race. One could almost read it as a comment on overpopulation, or at least on our species' prodigal appetite for replicating ourselves. Boltanski says that identity is an accident. One has a sense of infinite variations but something so prized seems here to be almost trivial. There is also the association with the brain itself, that this installation is a kind of analogue to walking into a mind in the very process of remembering.

Boltanski comes from Minimalist roots, evident in this 3D grid. But chance was also a favorite subject of the Surrealists. Fate, destiny and the unraveling of time in discernible patterns... this is not new ground to an artist who has been fearless in contemplating death in his work. What's new is tackling it from the other end: birth. Boltanski's own birth, he feels, was virtually a coin tossed in the chaos of the Nazi occupation. His existence, and ours, he implies, flickered into being in a moment that is mathematically next to impossible. Life fuses with death by being so close to never happening.

Usually babies make people feel warm and happy, with pleasant associations to humanity and family. This work makes one queasy, even threatened. It seems to replace the magic of childbirth, to some a sacred moment, with a sense of dread. There's a grimness to the violent repetition. Chance spurs the idea that children are produced merely to replace us, that we are all a kind of commodity with an expiration date. One wonders if those who have children have a very different reaction to the work than those who do not.

Monument: Les Enfants de Dijon (detail) 1986 [courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery]

People are always placed at some distance in Boltanski's work: disembodied, removed, represented by fugitive traces of themselves -- In Chance, by scrambled and fleeting photos. His is an art of vestiges. It's a very distinctive quality many have described, pointing to his focus on the ephemeral nature of our lives. But the more one talks to the artist, the more one sees a sly playfulness that finds release in the very morbidity of his subject matter. It's the same impulse that links 15th century memento mori to Alan Ball's Six Feet Under. Rather than be paralyzed by, or oblivious to, the inevitable, throw your arms around it.

Having had no formal art education, Boltanski began painting in 1958 but eventually settled into mixed-media installations. His work has long been about consciousness and remembering, which often touches on a posthumous reality we all careen towards or gaze back upon. People are recalled, but vaguely -- blurry photos, old clothing, withering objects dimly lit -- that have often pointed back to the Holocaust. (His Catholic mother hid his Jewish father during the Occupation, and Boltanski remains conflicted about his own Jewish identity.) Some of his work is not a great leap from the feelings one experiences at sites that commemorate the Shoah. The room at Auschwitz in which a vast pile of worn shoes is displayed is perhaps the antecedent to his mountain of clothes filling the New York Armory and Paris's Grand Palais. In both, as he says, subject becomes object.

Boltanski doesn't see himself as a particularly French artist. (He spends as much time in Eastern Europe, where he has family roots.) In fact, he admits that he asked the German authority if he could mount Chance in their pavilion, preferring that space. "The cliché about French art is true," he says irreverently. "It's a combination of cleverness and good taste." He's a born Parisian of Corsican and Crimean lineage, but he's human first, and his work will continue to haunt us all at least until, as he expects, he fades from collective memory. Perhaps the following video of the artist talking in his surveilled studio will make that fade a few moments slower.

Michael Kurcfeld is a documentary producer and journalist based in Los Angeles and Paris (http://www.stonehengemedia.com).