Co-authored by KC Deane, Research Assistant at the American Enterprise Institute

Joy Resmovits is one of the best education beat writers publishing today, so we were perplexed when she wrote a piece that so poorly reflected the realities of the contemporary education finance debate. While many (including President Obama) are focusing on whether the appropriate dollars (currently disbursed at the district level) are actually following students into the classroom, she reiterated the tired argument that "property poor" districts lack the funds to meet student needs.

A little background might be necessary. Public schools in the United States are funded through a combination of local sources (usually property tax), state sources (usually sales, but sometimes also property or income tax), and federal sources (income tax). Traditionally the majority of education expenditures were paid by local entities. In Ms. Resmovits's article, Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond was correct to point out that this led to huge disparities in funding between rich and poor districts. However, after a wave of education finance lawsuits in the 1980s and 1990s in which families in poor districts sued their states to more adequately fund education, this problem was--by and large--solved.

How was it solved? States, like Pennsylvania, developed so-called "foundation formulas" in which experts determine an amount of money that is necessary to provide students with an adequate education. The state then supplements funding for districts that don't have the property tax revenue to meet that minimum threshold. In Pennsylvania's case a "costing-out" study was conducted in 2007, followed by a reformed education funding law 2008.

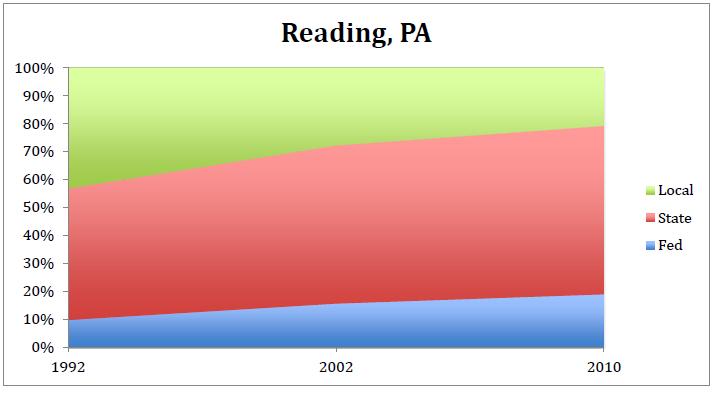

Ms. Resmovits was right to point to Reading as an example of a property-poor district that cannot raise enough local funds to support education. However, as the 20-year changes in funding show, the state has worked to remedy this shortfall.

As you can see, the percentage of total revenue taken up by local funds (the green section) has gotten smaller over time as the state and federal government have contributed a larger share to the funding of students' education. In fact, in the most recent year of data available, 2010, the state and federal share was over 81% of total revenue for the district. In her article, she quotes Cynthia Brown of the Center for American Progress who wishes to promote the "radical idea" that states should play a larger role in equalizing funding. It looks like this idea isn't radical at all, and is in fact close to a reality in Reading.

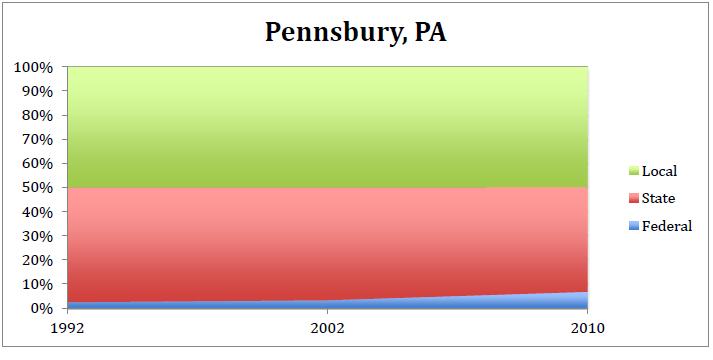

How does this compare to other districts? Let's look at Pennsbury, a tony suburb of Philadelphia:

Here we see the state and federal government playing a much smaller role, as the folks of Pennsbury have the funds to meet the adequacy threshold for their students.

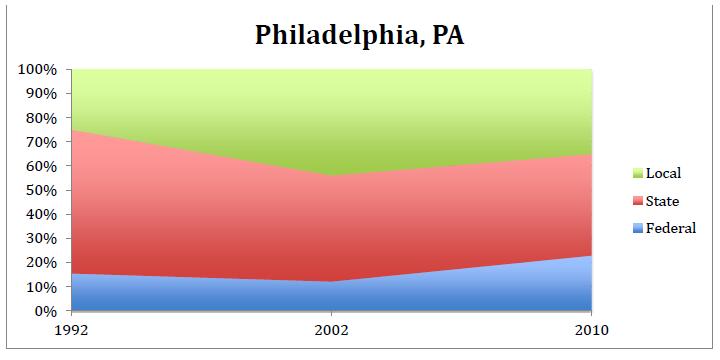

How about the largest district, Philadelphia?

Here, we see a middle ground between the two, and the largest federal involvement (most likely a result of Title I funding for the large number of poor students in Philadelphia).

What do these graphs tell us? They tell us that over time there has been a shift in funding mechanisms in Pennsylvania that encourages more state and federal support for poor districts, the very thing Ms. Resmovits and the experts she interviewed appear to call for. For those interested in knowing the overall levels of funding for each city, in 2010, Reading had $12,768 in revenue per pupil to spend; Pennsbury had $15,829; and Philadelphia had $17,088.

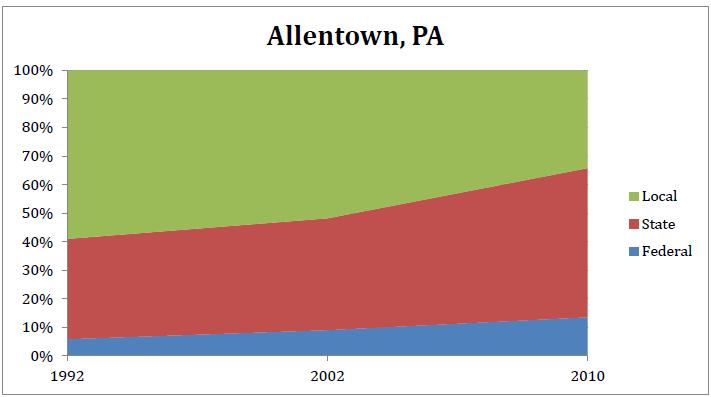

While it might appear that Reading is getting the short end of the stick, if we look at a demographically similar district, Allentown, we can see just how little of a burden local taxpayers in Reading have to pay.

In 2010, Allentown residents bore 34.3% of the funding burden whereas Reading residents had to bear only 21.4%. Allentown also had lower overall revenue per pupil at $12,458.

But, when we compare performance of these districts on state tests, we see Philadelphia, who receives the most money, performing the worst, and Reading and Allentown performing about the same. Pennsbury leaves them all in the dust.

Given all of this disparate information, it's plain to see that the story is more complicated than the property tax disparities between these districts. It is simply incorrect to say, as Ms. Resmovits does, that "largely because of the inequities that come with funding schools based on local property taxes, there's little order, not enough money and more cuts on the horizon".

What is the problem? Well in the words of Mark Twain "it ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so." So, we don't know why Reading is failing to educate its students. What we do know that just ain't so is that its problems stem from a lack of state and federal support.

Editor's Note: Following review of this post, the story in question has since been amended.