If many photographers have photographed America's war dead returning to Dover Airforce Base, few have described the experience and the sterile procedure involved. In honor of Memorial Day, BagNewsOriginals Editor and leading freelance photographer Alan Chin describes the ritual in what has now been five trips. For as formal as the process is, Chin's description, his experience and his photos have a surprising amount of feeling.

You can see the full set of photos, in full size, at this companion post at BagNews.

*******

I signed up in December to photograph the return of the bodies of American soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, and they approved my request. Bush never allowed us to document it, and Obama finally changed the policy last year. A small victory for free speech and access, although it's very limited.

They only give you about 6 hours notice before it happens, and the families have to approve media access; they do this quickly, in most cases the soldier was killed only a few hours before.

I went to my first one on December 3rd. After I received their email and confirmed, I rushed onto the New Jersey turnpike and headed south on a crisp and cold winter afternoon, shafts of light from the setting sun puncturing through the low-hanging clouds. After a while there was just a strip of gorgeous orange above the horizon, and then it was dark. It took almost three hours to get to Dover.

Two other photographers showed up, and we were met by Major Shannon Mann of the Air Force, a surprisingly friendly Public Affairs Officer. She had googled me and therefore knew a lot about me, had seen some of my work online; I'd never dealt with anyone from the military in such a normal way before.

But that was the nice part. Otherwise the rules for our coverage are pretty strict: No photos, or even contact, with the families. No moving away from the designated media area; no pictures of anything else on the base; no getting close to or on board the plane; no lingering around after the brief process is finished.

They gave us a short briefing about all that, a dog sniffed through our equipment, then we were taken onto the airfield and assigned a spot about fifty feet away from the plane. It was a big 747 modified for cargo so that the entire nose of it opened, from which a loading ramp jutted out with the two American-flag draped "transfer cases" on it. They don't call them caskets or coffins because these are "body-boxes" that get re-used.

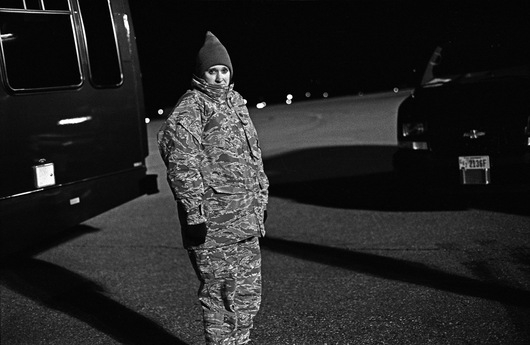

It was pretty stark in the dim light with an almost full moon; at first there was no one there. Then the bus carrying the families showed up but it was choreographed so they got out on the side away from us so we could not see them. One white van, what they call the "transfer vehicle," was parked on the tarmac and one soldier, a young woman, stood next to it. She is the "Transfer Vehicle Guide," whose ceremonial role it is to close the van's back doors after the bodies are loaded on board.

The procedure began with high-ranking officers and the pall-bearer details appearing, marching in formation. Since there were two dead that night, Cpl. Kenneth Nichols, Jr., of Chrisman, Illinois, US Army, and Lance Cpl. Jonathan Taylor, of Jacksonville, Florida, US Marine Corps, both killed in Afghanistan, there were two separate teams, one from the Army, the other of Marines, dressed in their different uniforms.

The Army went first, boarded the stairs onto the airplane, and emerged out the front. The loading ramp then lowered onto ground level with the coffin and the seven pall-bearers carried the body past the saluting officers, into the waiting van. The Marines then repeated the same. Not a sound could be heard from the hidden family members just a few feet from us on the other side of their bus. Another time, I could hear a woman, probably the wife or the mother, crying a terrible wail that was the only sound on the airfield.

The movements of the soldiers were slow and deliberate, giving us plenty of time to photograph. As soon as it was over, though, they drove us back to our cars, and wryly remarked that they would see us again soon. And they were right of course; I've been down there five times now, a bit frustrated at the limits of access, but also unsettlingly drawn into the ritual.

-- Alan Chin

caption 1: May 4, 2010: The remains of Sgt. Anthony Oneal Magee, Hattiesburg, MS, U.S. Army, died April 27 in Landstuhl, Germany, from wounds sustained in an indirect fire attack April 24 at COS (Contingency Operating Site) Kalsu, Iraq.

caption 2: December 16, 2009: Major Shannon Mann, USAF, awaits the unloading of the remains of Tech. Sgt. Anthony C. Campbell, Florence, KY., U.S. Air Force, who died Dec. 15 in Helmand province, Afghanistan, of wounds sustained from the detonation of an improvised explosive device.

caption 3: May 4, 2010: Left to right, A civilian contractor, a wife of an officer, and Captain Amber Millerchip, USAF, salute the remains of Airman First Class Austin H. Gates Benson, Hellertown, PA, U.S. Air Force. Benson died May 3 near Khyber, Afghanistan, of injuries sustained from a non-combat-related incident.