Wang Juntao arranges to meet me at a Starbucks at the corner of Broadway and 111th Street, across from Columbia University, his university pied-à-terre in Manhattan. I offer to rent a car and meet him at his home in New Jersey. "You might get lost," he tells me on the phone. "In any case, I have things to do at the university." He speaks warmly, as if we've known each other a long time. "How will I know you?" he adds. "I'm sure I'll recognize you," I reply. After all, Wang Juntao is one of the best known Chinese dissidents. Considered by the Chinese government as one of the "black hands" behind the Tiananmen student movement, he was condemned to thirteen years in prison, the most severe sentence imposed in the wake of the spring crisis of 1989 in Beijing. Freed for medical reasons in 1994 on the eve of American president Bill Clinton's visit to China, he has since been living in exile in the United States.

The intellectual and reformer arrives on the dot at the appointed hour, briefcase slung across his shoulder. He gets to the counter ahead of me and offers to pay for coffee. "It's the least I can do for someone who is interested in China's future," he says. We sit at the last available table, near the window. Outside, passersby brace themselves against a December wind. The sky is the colour of steel. I put the tape recorder on the table and ask Wang Juntao to tell me about Tiananmen.

"On the evening of June 3, 1989," he says, "I was to meet, as I did every day, the student leaders for our daily strategy meeting. I showed up at the hotel where we had our headquarters, not far from Tiananmen Square, but no one was there. I sent my driver to see what was going on. He returned, telling me the army was advancing toward the square. I ran over. I knew it was the end. My only objective was to save the student leaders from the massacre that would take place. To do so, we had to leave Beijing. I left to look for them with my chauffeur. There were huge crowds everywhere."

At Tiananmen Square, few protesters were left. Many, faced with the rumour of military intervention, had gone back home. The student leaders who were still there decided, in a last stand, to take an oath to the cause they had been defending for more than a month. They knew their struggle for democracy was lost. Already, the tanks of the People's Army were advancing toward the square; in the distance shots could be heard. Deng Xiaoping, patriarch of the Communist regime, had decided to put an end to the student revolt. West of the city, in the working-class neighbourhoods, hundreds, perhaps thousands, of civilians, believing that the army would not fire on the people, fell to the bullets of soldiers or died crushed under the tracks of the tanks.

"We swear to protect the cause of Chinese democracy," the students proclaimed in unison. "We aren't afraid to die. We don't want to keep on living in a troubled country. We will protect Tiananmen to the bitter end. Down with Li Peng's military rule!" The square, in which a few days earlier close to a million demonstrators had gathered, now contained only a few thousand. The ground was littered with tents and debris. Resigned to martyrdom, the students awaited the final assault.

The army had difficulty advancing. Ordinary citizens erected makeshift barricades by placing buses crosswise in the street. A labour union distributed shovels and pickaxes to its members. Some of them knocked down the wall of a building site to allow people to arm themselves with bricks and stones. On Fuxing Road, a main artery several kilometres to the west of Tiananmen Square, thousands of people formed a human chain to block the army's advance. The government, doubting the loyalty of the soldiers camped in Beijing, had called up detachments from the provinces, who were considered more obedient. They fired warning shots. But the human chain refused to back down. The soldiers then fired into the crowd.

At Fuxing Hospital, there were no longer enough doctors to treat everyone transported there by makeshift means, on bicycles, motorcycles or even on doors used as stretchers. Inexorably, the military continued its march to "free" Tiananmen Square. The crowd drew back but showed no mercy to the soldiers when it managed to get its hands on them. Two soldiers who tried to extricate themselves from a tank set afire by Molotov cocktails were beaten to death. In a brutal burst of violence, the crowd clubbed open the skull of one of the soldiers.

Around one o'clock in the morning on June 4, the army finally surrounded Tiananmen Square. The military used loudspeakers to tell protesters it had orders to put an end to the protest. The government branded the occupation an anti-revolutionary movement, which is, in Chinese political vocabulary, is tantamount to treason. A few students tried to convince the soldiers to put down their weapons; one was killed point-blank. The determination of the student leaders wavered. Those who, a few hours before, swore to die rather than to give up were not driven by the same hatred or the same courage as the workers or ordinary people who barred the soldiers' way at the cost of their lives. The students didn't believe it would come to this. When they began to demonstrate, in May, after the death of the reformer and former chairman Hu Yaobang, it was to call for the end of corruption and more transparency in the party. No one dreamed of overthrowing the regime. They even believed they had the support of Zhao Ziyang, the general secretary of the party and second-in-command in the regime after Deng Xiaoping.

Chai Ling, nicknamed the Joan of Arc of the student movement, addressed the last protesters gathered around the Monument to the People's Heroes. "Those who want to leave should go," she told the group, "and those who want to stay, stay." While the elite troops, assault rifles at the ready, advanced toward them, the students voted with a show of hands. A majority decided to leave. Not far from there, Liu Xiaobo, a young academic and literary critic who had returned home from the United States to take part in the Tiananmen Square movement, had begun a hunger strike two days earlier with three other activists, one of whom was a young rock singer. Determined to prevent what seemed like an imminent massacre, he stepped in to mediate between the army and the students. Thanks to his intervention, the military agreed to let the students go. Escorted by the soldiers, they left the square singing "The Internationale" and calling the soldiers animals and fascists. In an absurd parody of their struggle, the effigy of the American Statue of Liberty they had erected across from Mao's portrait was unceremoniously knocked over by a tank. Some students were arrested; others managed to flee. China's democratic spring ended in blood, humiliation, and escape.

[break]

More than twenty years later, the man seated across from me in a New York café does not seem bitter. Even though all of his former life has been lost, even though he spent more than four years in prison, even though he may never see China again in his lifetime, he remains optimistic. Yet Wang Juntao knows better than most that the future of China's political reforms will probably be at a standstill for a long time. He knows that the conservative elements in the regime, at least for now, have the upper hand... He knows that Western premises relating to China's democratic evolution have been proven false. He knows Tiananmen Square's opportunity for democracy has not simply been postponed but that the country is experiencing an authoritarian change in policy that allows for no political reform. He knows as well that the village elections that were supposed to sow seeds of democracy in the Chinese countryside instead guaranteed the stronghold of Communist officials on local government.

Some exiled veterans of the fight for political reform like to say, in an irony tinged with bitterness, that while they have found a haven of freedom under foreign skies, they have lost the land of China. Reconciling heaven and earth was the duty of ancient emperors. Any progress on political reform in today's China, however, cannot happen until Chinese leaders come to the conclusion that fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression and the right to choose one's government, are the best guarantee of China's development. Reform cannot occur until the leaders decide that the cost of taking no action is higher than the cost of change. Only then can the exiled veterans of the democratic struggles, who paid so dearly for their commitment to their ideals, hope to leave foreign soil and return to a land of freedom.

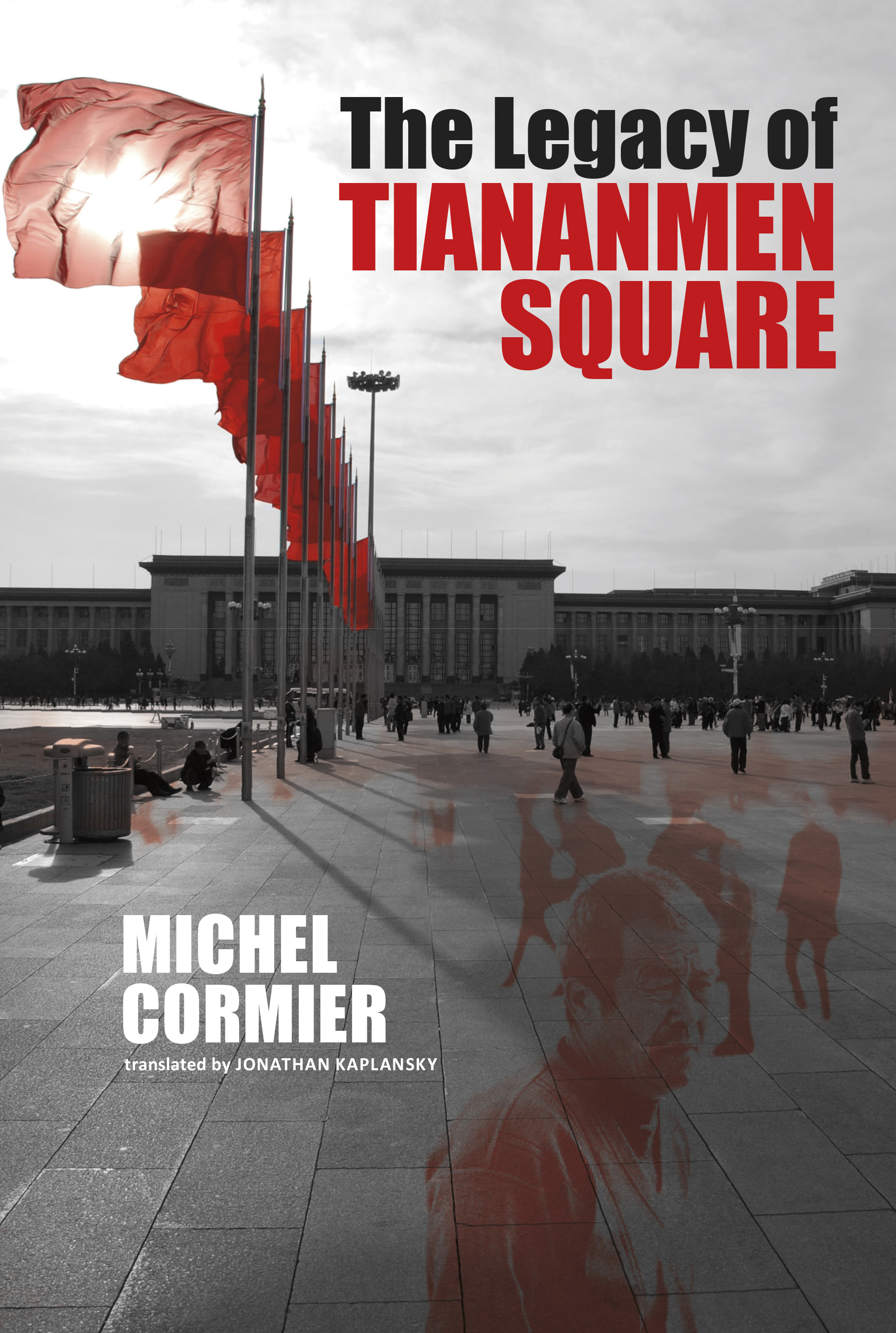

Excerpted with permission from The Legacy of Tiananmen Square by Michel Cormier, translated by Jonathan Kaplansky. Published by Goose Lane Editions.