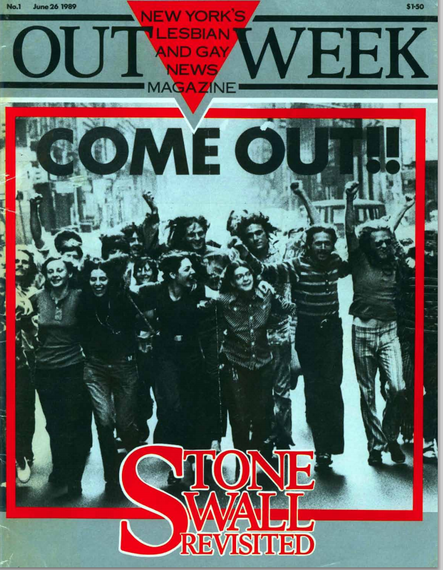

The first cover of OutWeek (June 1989), which depicted a poster for the first post-Stonewall publication from 20 years earlier, Come Out!, which featured a photo of members of the Gay Liberation Front in 1969.

Twenty-five years ago this month a revolution in journalism was born in New York. It was called OutWeek magazine, and though it only lasted two years and may not be well-known today, it had a major impact on journalism and certainly how queer issues would be covered. It presaged the Internet age, helping redefine advocacy journalism. It forced its way onto the front page of The New York Times and network news broadcasts. And it inspired a neologism, "outing," a word now used to describe many things, and a specific phenomenon with regard to closeted gays in the public eye, still much-discussed today. It's time to celebrate its 25th anniversary with a look back.

OutWeek was founded in June 1989 by editor-in-chief Gabriel Rotello, a writer and musician, and publisher Kendall Morrison, who was a phone-sex entrepreneur, during the height of late-'80s AIDS epidemic, when so many of us became politicized, literally fighting for our friends' and our own lives. I was a co-founding editor -- features editor -- along with Andrew Miller, our news editor. Soon we were joined by editors Sarah Petitt and Victoria Starr. Most of us who were editors and reporters had journalism backgrounds, but we, as well as most of the editorial, production and sales staff, had also come out of the AIDS-activist group ACT UP or other grassroots queer groups, tapping into the new radical queer politics of the time.

OutWeek was inspired by a lot of the New Left journalism of the previous decades, as well as the stellar reporting of groundbreaking gay publications like Boston's Gay Community News, but infused it all with a lot of biting sarcasm and much fun, as well as a queer sensibility that was unmistakable. And, believe it or not, OutWeek was the first to call itself a gay and lesbian magazine. Previously, the two communities were split in terms of news magazines -- and the bisexual and transgender communities were even less defined -- and we decided to come together, changing queer publications like The Advocate from that point on, while often having knock-down, drag-out fights among the editors over gender politics.

The weekly newsmagazine broke major stories that splashed the front pages of the New York tabloids and The New York Times, such as when Mayor David Dinkins brought in a health commissioner, Woody Myers from Indiana, who, we revealed, had advocated for quarantining people with AIDS. Or there were Gabriel Rotello's exposés about Father Brude Ritter and Covenant House, one of the earliest Catholic Church sexual-abuse scandals and one of the most widespread.

OutWeek's commentary, too, was covered above the fold on the front page of the Times, such as when Marion Banzhaf penned a jarring do-it-yourself abortion column amid the New Right's assault on women's right to choose. Gay male activists and lesbian feminists certainly saw the issue of women's choice and the right to our bodies as integral in those days when sodomy was still illegal in many places. OutWeek published an "I Hate Straights" cover that caused a firestorm like I'd never seen, inspired by its reprinting of an essay given out at Pride by "anonymous queers." The magazine was at the forefront of activism in a time of life or death, but also at the cutting edge of nightlife, the arts and queer culture during an interesting and actually quite fabulous time. Our film and theater criticism were referenced across the country; up-and-coming drag stars, from RuPaul to Lady Bunny, often graced our covers; and celebutante and club kid James St. James, who wrote his often sardonic, sometimes poignant "Diary of a Mad Queen" column, was a must-read.

When I say OutWeek presaged the Internet age, I mean in the true sense of netroots organizing and the influence of blogs, and commandeering the mainstream media, forcing stories into the major dailies and the television news. We also pushed the left, which we saw as ineffective, and were often under attack from a very defensive Village Voice (writer Gary Indiana compared me to an infant "crapping in his diapers"), as well as from the right for taking on the rabidly right-wing Pat Buchanan, Pat Robertson and The New York Post, whose editorial-page editors and columnists regularly skewered us, even one time having the gall to call us McCarthyites. OutWeek printed phone numbers of editors or politicians for people to call, and the editors of New York magazine, Cosmopolitan and Vanity Fair were favorite targets for their sensationalistic coverage of gay issues at the time and the fear mongering they often created around AIDS. And the publication took on Hollywood executives big-time for anti-gay portrayals in films. These were called "phone zaps," which were the equivalent of emailing, Facebook sharing and tagging or tweeting today. There were even "fax zaps," which would have the target's fax machine going all day.

And then there was the topic of "outing," which I've written a lot about before, and which I was thrust into with my "Gossip Watch" column, literally a watch of the gossip columns and how they closeted celebrities and politicians. But the outing issue actually all began, believe it or not, with a box called "Peek a Boo," which had a list of well-known names in it -- that's it. News editor Andrew Miller and I just sat around one day thinking up names to put in the box. It's hard to believe the sensation this caused. The fashion bible W magazine soon put OutWeek on its coveted "In" list -- even though it was really out, so to speak. OutWeek was on the newsstands of New York, so it couldn't be ignored. Time magazine writer William Henry III, who I'd later learn was a closeted bisexual man (and thus had a conflict of interest), coined the negative, violent term "outing" regarding OutWeek's reporting, and it blew up big-time after my cover story, "The Secret Gay Life of Malcolm Forbes." (Yes, it was controversial then to out even a dead man.)

So many of OutWeek's editors and writers went on to do amazing things, becoming acclaimed novelists and playwrights, documentarians and authors. Sarah Pettit, our arts editor, would go on to found Out magazine with another OutWeek alum, former columnist Michael Goff. She then became Arts and Entertainment Editor at Newsweek before her death at the age of 36 in 2003 due to cancer. I miss her so very much, as well as many other enormous people I loved who were part of that feisty magazine, who succumbed to AIDS in those years but who made a massive difference in their short lives. Like many great things, OutWeek went out in a blaze of glory in June of '91, stirring still more scandals while also at the center of a financial power struggle too complicated to go into here but which brought it to an abrupt end.

Happy 25th anniversary, OutWeek! You changed my life. You changed all our lives. You changed the world. And we're forever grateful.