A Conversation with Sammy Hagar

Mike Ragogna: How are you doing, Red Rocker?

Sammy Hagar: I'm doing great! I'm just getting ready to rehearse and start my whole campaign that goes through until probably November.

MR: And you're going to be supporting the new Sammy Hagar & Friends release, right?

SH: Yeah. And it's like these shows I'm going to do. I'm going to do TV, you name it. Photo sessions... my least favorite thing on the planet.

MR: Are some friends going to be joining you on the tour?

SH: Well, hopefully. When you have the kind of friends I have on the CD, it's pretty damn eclectic. These guys are probably either touring or out of the country touring or on vacation or doing something. I'm not sure who's going to be around when I'm around, but I'm taking a lot of the people out on certain shows, like in Saint Louis and San Francisco, I'm bringing Denny Carmassi and Bill Church--the Montrose guys--and in San Francisco, a guy that's not even on the record, Dave Meniketti from Y&T is going to play the Montrose stuff with us, and Michael Anthony is coming out for most of the tour to do the Van Hagar-era stuff. I've got some people I'm bringing around with me, but if I hit Detroit and Kid Rock's around, hey hey hey! If I hit Nashville, I'm sure Ronnie Dunn will be there...

MR: Well, with an album titled Sammy Hagar & Friends, and given how many musical friends you have, how did you know who to ask to join you on the record?

SH: You know what? That's a damn good question, Mike, I've got to tell you, because it started from what I do in Cabo every year, my birthday bash, and I've had every friggin' human being in the music industry was down there and played with me over the years. So to have that big well of talent and artists and then try to get them all on ten songs is like, "Whoa!" I have so many of friends that went, "Aw, man, why didn't you ask me to do it?" I really tried to go with two things: What was right for the song, like Nancy Wilson; she was the right harmony for that. She's a real great harmony singer. Ann's such a great lead singer, Nancy always is usually defined to doing the background vocals, which are brilliant on Heart stuff. She's amazing and a great lead singer herself. So she was a first choice. "Mickey Hart, he's right for the drum part on this because he has such an eclectic drum collection of Arabian drums, African, Tahitian drums, you name it, he's got them," so I knew he was the guy. It was just kind of like that. I knew who was right for the song. Kid Rock, "Knockdown Dragout"... I needed an edgy guy, a guy that's got an attitude, a guy that's a little harder-edged than the country boys. It's just like that. "Toby, hey, it's perfect for 'Margaritaville'!" We've been drunk on tequila and Cabo Wabo so many times and walked up on stage and played probably more than Jimmy does in his own places. There were a lot of people who said, "Oh, God, I'd love to do it but..." I called Chad Kroeger from Nickelback to help me out on one song and he goes, "Dude I hope you're not in a hurry, I'm producing Avril Lavigne's record, I'm writing with her, and I'm doing a world tour." It was just really about who could and who couldn't.

MR: Sammy, as far as the tracklist, how did you choose these covers? I know Bob Seger's "Ramblin' Gamblin' Man" was recommended by your wife.

SH: Yeah, and I'm a Seger guy. We were on Capitol Records together all those years and then I did shows with him even back in the old days. I remember with Montrose, we played outside Detroit...Ann Arbor or something. It was an outdoor thing. I didn't even know who he was and he blew my mind because he sounded the way I wanted to sing. He sounded like an old blues guy already and I was a young kid. My voice was trying to sound like that. But just picking the right songs, like I said, that meant something to me or this group of people, like when we did "Going Down" with Neal Schon and Mikey and Chad. All of us had jammed "Going Down" at the Cabo Wabo or even at concerts when they'd come and sit in. For me, it might be the number one song I jam with people. That and "Rock Candy," because that's what everyone wants to play. They're like, "I know 'Going Down,' let's play it." To put that on the record was just like, "Yeah, this is about my friends getting together. This is what we do." So the idea of that was that. "Personal Jesus," there's no reason other than it's a cool, badass song and it's a cool, badass riff. I heard it on the way to the studio and we all agreed, "Let's try it." I think it's killer. It might be my favorite cover I've ever done.

MR: Yeah, and though one wouldn't exactly think of Sammy Hagar covering Depeche Mode, it's a smooth ride, the way it turned out.

SH: Yeah, I know it isn't the obvious, but if you listen to that riff--it's played on a synthesizer--you could play that riff on a banjo and it sounds badass. [hums riff] It's a mean blues riff and they did it so electronic and it was still heavy. To me, it was badass. I hadn't heard that song in years and when I got in the car and I was driving to the studio the other day, I heard it and I said, "Wow, let's do that!" That's a good place to be. I've got to tell you, Mike. That's what I'm most proud of on this record; it's fearless. Bring it!

MR: Yeah, YOU'RE fearless. By the way, what guitar are you playing these days?

SH: I'm still a Les Paul through a Blackstar/Marshall stack. You can't take it away from me. I can't help it. I'm a Gibson guy. Other than my acoustic work--I play a lot of acoustic guitars on this record--my only other thing was a Strat. On "Ramblin' Gamblin' Man" I played a strat, and that was John Cuniberti's idea. He said, "Why don't you get that kind of sound for this?" and I'm going, "Gee, I haven't played a Strat since 1977," but I pulled one of my old strats out and it sounded great; it made me play different. I've never played a solo like that. That does not sound like a traditional Sammy Hagar solo.

MR: Will you be playing more Strat in the future?

SH: No, I don't think so. To me, playing a Strat's a wrestling match. I love the way they sound, but I just can't play them. [laughs] Maybe I'll put a Les Paul neck on a strat.

MR: [laughs]

SH: I'll bolt my damn Les Paul neck onto the Strat.

MR: Hey, let's talk about the songs on the album. "Winding Down" has a pretty cool topic, and you've got Taj Mahal on it...

SH: I don't know if the media has tuned into this or if I'm just getting hip to it, but it seems like it's all tragic. Everything is tragic, everything is trying to incorporate fear into people, and people are doing all the craziest s**t--going into a school and blowing away all these kids. Anybody that could do that, I just can't imagine why people could be that sick. So it repulsed me. One morning, I got up and my wife had the news on. I don't watch the news, but all of a sudden, I watched it and I'm sitting there drinking coffee and a guy kills everybody in a classroom, and they've got the guys that blew up the people in Boston, and then the Chinese dude who says it's okay to bomb America or something. I saw all that in one day and I was just driven to my guitar. I don't usually do protest songs, I don't make statements except for "I Can't Drive Fifty Five," which, honest to God, is a protest song. That's the kind of protest song I write. But to get political and all that, it just repulsed me; I got furious, almost, and I had to speak out. My guitar was already tuned to an open G tuning, which is so bluesy you can't play anything but the blues on it, so I just started playing that riff and it came out in five minutes. It wrote itself. That was the quickest writing on the album I did, and I didn't change a damn thing. I went to the studio that day and recorded it like that except I added another verse later for Taj. I wanted him to do some answers in there. It's a weird thing. To me, it made me want to get out the ol' Neil Young "I'm moving to the country 'cause it's time to go." I felt like, "You know what, I just want to get out of this fricking whole mess here." The world's revving up and I'm winding down. I'm over it. I don't even want to know about it. That's where I'm at in my head.

MR: Wow. You have a Chickenfoot connection happening on "Going Down."

SH: Yeah, that was the first idea that I wanted Joe, Chad, Mike and myself to do live in the studio, and Joe was gone, he was in Europe. So I got Neal to do it. I'd already gotten Joe to play on "Knockdown Dragout," so I just said, "Okay, that's cool, I'll just get Neal Schon to do it" because I needed to get Neal Schon on the record, too. He's one of my old, dear friends and we've played together so much. It's just such a classic jam tune. Chickenfoot, the original, before Joe. Chad, Mike and myself down in Cabo for five years played that song every time we were there, and we were there at least five or six times a year and played two or three night each time, so we probably played "Going Down" forty times a year. Then the first time Joe joined us in Las Vegas, what did we play? "Going Down." And then we played Led Zeppelin "Rock And Roll" and then we played "Dear Mr. Fantasy" by Traffic, which I've never played again. I'd never, ever played it before. But "Going Down" was always that song, so to play Sammy Hagar And Friends, to put that CD together and have those combinations of people on there and say, "Well what are you going to do, write a new song or cover something?" I'd say, "Let's do 'Going Down.' What would we do in Cabo? We'd play 'Going Down.' Let's go play 'Going Down.'" That was the reason.

MR: Nice. And there is another nod to your past with "Bad Motor Scooter" that was from these sessions.

SH: "Bad Motor Scooter" is on the extra downloads and all that. That's such a wonderful rendition of that song. Having Denny come on and sing with Bill Church and myself, you've got three of the original members and it was the first song I ever wrote in my life. The first song I ever wrote in my life was "Bad Motor Scooter." Can you believe that s**t?

MR: [laughs] Awesome

SH: And then after Ronnie's death, we did that tribute for his family to raise some money and Joe played. It was just so magic having Bill Church and Denny play on that thing, and it didn't have any purpose. There it is, I own this track. For a year now, it's been sitting on ice and I thought, "The world's got to hear this." There were only sixteen-hundred people or whatever it was that the Avalon Ballroom holds, so that's all the people that got to hear. But I wanted the world to hear that because that was a magical night between the four of us playing that Montrose stuff. It might have served it better than it's ever been served.

MR: Sammy, there are so many phases of your career, and yet whenever Sammy Hagar comes up to the mic or plays, it's Sammy Hagar, even when it's Van Halen or whatever the configuration. It's like you can't water down the personality that comes out in the voice or the guitar.

SH: Well, this is a good question. Nobody's ever asked me this, but I have a theory. When I was first starting and I was trying to sing and play like other people and I was trying to learn other people's songs, I could never learn them. I could never sound like anybody, you know? I had a problem with it. I'd be in a bar band and I'd be playing a Rolling Stones song trying to sound like Mick and I couldn't! I just wasn't good at learning other people's songs and styles, so I always had my thing by accident. It's almost like I felt I wasn't very smart musically, I didn't have any musical training, so I couldn't learn those riffs the way they played them. I ended up playing them in my own style. It turned out to be a blessing in the long run because I kind of developed my style even when I was trying to play other people. So I've seen bands, like my band at the Cabo Wabo, Cabo Uno. I walk in, go up to my dressing room and the doors are closed and I don't know whether it's music being played over the PA or whether it's the band. I'm sitting there and I find out it's the band and I go, "Holy shit, they sound exactly like the record!" Well, that's a curse. I figured this out now. In the old days, I was always trying, but now, today, I'm going, "I was a very lucky guy there, I just kind of happened to have my own stamp," and I certainly refuse to bend too much, that's when I got kicked out of bands all the time. But I've got to do my own thing. I'm not good at being produced, I'm not good at being directed. Some producers, I bump heads with them because they're trying to get me to do things, and I go, "I don't want to do that, I can't do that, that sounds horrible to me!" So I'm just one of those guys. That's my secret: I'm kind of hardheaded and limited. I'm limited to myself.

MR: Sammy, what do you think of the state of rock these days?

SH: I don't know. It's interesting. Thank God I already made it. I don't see a guy with my style and the way I went about it doing too well today. My way of making it, I think, is dead and gone but I still believe that if you want to be a musician... If you want to be a pop star, it's different. You've got to go get on TV or something. But if you want to be a band, a rocker, a guy that can play music and jam with other people and be a real musician, then you've just got to go play as much as you can in front of as many people as you can any time, anywhere and live and breathe it. Put your head down and keep on swinging. One of my favorite new young bands is Rival Sons. Their last thing was called "Keep On Swinging," and he's the same guy who wrote that song "Not Going Down" on my record. He's got that attitude. A young guy from Fontana, my hometown, he wrote a song called "Keep On Swinging" and he wrote "Not Going Down." That's the attitude you've got to have today. If you're going to go out and do what I did, you'd better have your f**king head down and just be swinging. To try to outsmart the system and find a way to do it but then still be a musician, you've got to play music, you know? I don't know if it's going to get you anywhere. You'll get somewhere. I don't know if it's going to get you rich and famous by doing that, but you'll get somewhere. People will start noticing you. That's just my advice, whether you asked for it or not. That's what I think of the industry right now, it's tough, but keep your head down and keep f**king swinging. Kick, bite, everything. Cheat.

MR: [laughs] Cheat?

SH: [laughs] If you have to!

MR: I usually ask for advice for new artists, but I think you just gave it.

SH: [laughs] Yeah.

MR: It must have been a nice moment for you on the album to have "Father Sun" and to also have your kid Aaron on there with you.

SH: Yeah, that was a last-minute thought because I didn't have a duet planned for that song, and if I did, I thought about a female because of the verses. It's kind of romantic. I love that song, by the way. It was so personal. I went on vacation with my family to Tahiti. I didn't have a guitar, nothing, and I heard that wonderful French Polynesian music, which was just killer, so I bought those instruments, I played them on this song, I had other guys come in and play those instruments on that song to try to really capture that vibe and I thought, "This could be a good duet with a girl." The first person I thought about was Grace Potter because she's really cool. She's awesome and I thought about her but she was on tour, so I couldn't get it done, and she was supposed to come to Berkeley and San Francisco. That's the window we had, and I'm going, "My record's done." Long story short, I said, "I'm going to have Aaron." At first, I called it "Waiting On The Sun," because that's what I was doing every day over there--time change, wake up at four or five o'clock in the morning, and go, "S**t, when's the sun coming up?" Kids are going, "What are we going to do, daddy?" "Well, we've got to wait until the sun comes up, you know?" We were waiting on the sun all the damn time...and then I thought about how powerful the sun is, how it has that power where it drives you out. It pulls you out of your house and it pulls you out into ocean and onto the beach. I love that song, but when I renamed it "Father Sun," I thought, "What a twist, I'll get Aaron to do it." It was a spontaneous thought. I was asked about Mumford & Sons and The Lumineers and all that. Well, I wrote this in December '12 with that kick drum of mine because that's what they were doing in Tahiti. Every night at this little resort I was at in Taha'a--a little tiny island with about sixty people on it--every night these guys would come and play at our resort, and they had a lady with a stick and a tom-tom. She'd go "Boom, boom, boom," just like what I put on there with a kick drum, and I did the same thing on "Winding Down," which is an old blues thing. Then I come home and I hear these songs and I go, "That's it! That's exactly what I want!" I love those bands. I love that traditional, earthy... it's world beat when you think about it. It can be in the Ozarks, it can be in Louisiana, it can be in Chicago or it could be in Africa or it could be in Tahiti. There it was, you know? Just someone hitting the downbeat. "One, Two, Three, Four," four on the floor, man, AC/DC kills it electrically, but when you do it acoustically, it's badass, too. So that was the influence of that song, and Aaron sang on it and did all the "Whoops" and all that because he'd already been listening to all that music and I hadn't really heard it. My seventeen-year old daughter played me "Ho Hey" by The Lumineers. When I played her "Father Sun," she said, "Oh, that's sounds like The Lumineers." She played me it and I went, "Wow, I love that." That's one of my favorite records. It's just exactly what I was trying to do at that time.

MR: Now the song you had for the NFL was "Knockdown Dragout."

SH: Yeah, that's an ass-kicking tune. That's a jingle...that is a rock fricking jingle. It's two minutes and twenty seconds, it's the shortest song, it's so high energy, you don't even have time to take a breath when that sucker comes on. Like I said, I had to get Kid Rock to do that. I needed an edgy guy. I'm not going to ask Toby Keith to sing on it, or Kenny Chesney. He's my missing guy who didn't get to sing on this record. We were planning to do "Eagles Fly." I was going to do an anthology record first with a new song from each era and then I was going to redo "Eagles Fly" with him because it's his favorite song, and then that got blown up because I decided to do the whole CD instead of the greatest hits record. I was going to ask Kenny to sing "Knockdown Dragout," but Kid Rock, I asked him to do it and he did it the next day. I love that guy, he's high-energy, hard working, he's the real deal and he's such an eclectic rocker, he belongs as one of my "Friends." Kid Rock is definitely a buddy, he's like me. He's pretty fearless. He can rap, he'll do country, he don't care. "What do you want to call me? What do you want to say? You're not going to tell me I'm limited!"

MR: Nice. Obviously this begs for a Sammy Hagar & Friends 2.

SH: Or a tour! That's what I really want to do. For my birthday bash on October thirteenth, we're trying to get a live TV broadcast around the world from Cabo on my birthday and I want to get as many people as possible to come down and do the songs with me. It'll be a great way to take the whole damn thing out there. Maybe next year. If the record's big enough, I'll get it done. If it's like every other classic rocker that puts a record out and it just kind of comes and goes, then maybe it won't warrant it. But I want a number one record, I want a Grammy award, I want everything! I've still got the fire up my ass so far that you can't even believe it. You think, "Why does this guy keep doing this?" because I love this s**t, man. It's awesome. Can you dig it?

MR: I can dig it. Sammy Hagar two years from now. What happened?

SH: Who knows. I've got my head down and I'm swinging the whole time. I ain't looking up, so every now and then, I bump into something. "Oh, that's cool," and I start doing that. So I would love to do some more with Chickenfoot, I would love to write another book, a lifestyle-cookbook-party, how to get together with people in your backyard and in the kitchen and my eclectic drinks and stuff that I make. I'm a real connoisseur of all kinds of stuff and I'd like to put a book together like that to show people how I like to live. I would like to have a TV show, but not featuring me...I'm crazy! I don't know. In the next two years, I'll take whichever one pops in, gets in front of me and I say, "Okay I'll do that one now." I'll do anything, like you said. I'm fearless.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

MANICANPARTY'S "MONARCH"

photo credit: Adam Ross

This video's got it all. Foamy waves crashing on untouched sand? Check. Tribal dancing through fields and flowers? Check. Fun, fun, fun 'til their daddy takes the T-Bird away? Check and check.

So according to Manicanparty...

"It's ironic. Even though this song stemmed from a troubling experience, the end result reflects something completely different. An upbeat lively song that reflects a sense of renewal and celebration. Traveling from one mental space to another. A metamorphosis which we all go through at one point or another."

A Conversation with Chick Corea

Mike Ragogna: Hey Chick, how are you doing?

Chick Corea: I'm doing pretty good, I'm doing really well, thank you. I'm out on tour, I'm in Albuquerque, the sun is nice and hot and dry, and I'm getting ready to do ten days at a classical chamber music festival up in Angel Fire.

MR: Beautiful. Of course it's your material, right?

CC: Yes, mostly my stuff. I didn't have any time to prepare any Mozart. They wanted to play Mozart but I didn't have time to get it together. But I did write a brand new piece of music for the lady whose festival it is. Her name's Ida Kavafian. She's a great violinist and an old friend of mine.

MR: Beautiful. Relationships are important to you and inspiring as far as your creativity with music, aren't they.

CC: Oh they're everything. They are the richness of my life, man. My musician friends and the great people that I play with, that's my life. That's what it is. I particularly have stayed right in that area as a composer. That's what I do; I write for myself and the musicians that I play with. I've yet to take commissions to write for other people or movies or anything like that. I'd like to try that, but that's not what I've done.

MR: Chick, your new album, The Vigil, features, basically, a new band configuration though it's mainly "Chick Corea." This is the first time you're playing with these Vigil cats. Can you go into how this particular ensemble of new musicians came together?

CC: Of course. It's a long story, but it maybe starts back ten years or so when I first stopped having a steady group of my own. I think one of my last groups was Origin, a sextet that I had with Avishai Cohen on the bass and Jeff Ballard and three horns. I started doing a lot of collaborations with friends--with Gary Burton, Bobby McFerrin and Bela Fleck--and trios with Christian McBride and Brian Blade. A lot of different stuff. It was all very exciting and interesting, but ten years went by real quick and I realized I didn't have this platform that I really like to have as a basis for my music, which is a band of musicians that play my compositions. I decided that I needed to put that together again for my mind and my soul and so forth. That was the general impetus. And then 2013, that was the year that I said to my manager and my agent, "This is what I want to do," and then I started going around trying to assemble a band. I put together this first group, the one that you hear on the recording, with Hadrien, Charles, Jim and Marcus.

MR: This project represents a certain amount of improvisation. What was the process like when you created the material for it?

CC: Well, a lot of it happened in my own mind because as the idea developed, I started to cull music together from stuff that I had written already. I had written a bunch of pieces for the reunion of Return To Forever, which we never used. I took one piece, the piece called "Galaxy" from there. I wrote a couple of new pieces--"Portals To Forever" is a new piece, and "Planet Chia" is a new piece. But because I wanted to have a recording out before the tour so that people could see when we say, "Chick Corea and The Vigil" what the heck that is. The idea of the record was to show them, "Well, this is a band and the first attempt to put music together for it." What I did was I sent the music to the guys after I got their commitment to do the tour and everything and we got together in the studio for five days and just recorded it straight down. There wasn't any prep time. I would have liked to have been able to take the band on the road and then record, but there wasn't time to do it. They're all such consummate musicians, they were able to play the heck out of the material.

MR: Why "The Vigil?" Why that moniker?

CC: You know, I wanted to give the band a name rather than just "Chick Corea." I wanted to give it a name so that our label would show that this is my music, this is the music that I've put together, it's not a collaboration yet, anyway. "The Vigil" was the concept that came to mind because that's what I find that I'm trying to do. I'm trying to keep my attention focused on the quality and beauty of the culture of the music that I come from. The jazz music, the classical music, the Spanish music, all the various contacts I've had with the great musicians in my life, and thus one of the pieces is called "Legacy" after that kind of flow. So that would be the idea of "Vigils"--to keep the attention strong on high quality music.

MR: Yeah, and I can hear that it doesn't only represent a lot of your newer approaches, but also in a legacy-ish way, revisits the vibe of the stuff you've done in the past. For instance, "Planet Chia," to me, ended up like material on My Spanish Heart. Would it also be fair to say that this would be one of your legacy projects?

CC: The legacy that I'm referring to with the song title is not my legacy, it's the legacy of the culture of music that I feel like I'm honored to be a part of. It goes back, you could say, to the beginning of the 1900s with Louis Amrstrong and Duke Ellington's band, and then, actually, if I widen the influence a little bit and take it back into Europe back to the 1800s and 1700s to go back to Bach and Mozart, the legacy ties together that way. To me, that's the legacy that I'm talking about.

MR: Okay, this to that to that giving birth to that and that.

CC: Yeah, it's the true look at what a culture is. It's how a culture gets formed, it's what we call a culture. I'm part of that. It's been part of my life. One of the transitions that I took the opportunity to use for the record was the one track with Stanley Clarke. We performed that piece at the Blue Note on a week that we put a band together that had some of the guys that would be in my new band. It had Charles Altura, the guitarist, and Marcus Gilmore, the drummer. We played a week at The Blue Note in New York with Stanley, and that particular piece, we played it one time. It's called "Pledge For Piece," and it had such a bite to it that I wanted to include it on the record. Plus having Stanley on the record is really nice to me because he's part of my flow of music and Return To Forever in the seventies and so forth.

MR: And you had Ravi Coltrane on that track.

CC: Yeah! Ravi's a favorite of mine, man. I'm going to ask him to come and sit in with the band when we play our date in New York in September. That was another interesting point about that band at The Blue Note. Ravi is, of course, the son of John Coltrane, and Marcus my drummer is the grandson of Roy Haynes. The legacy continues, there they are in front of me, playing great and fifty years my junior.

MR: All uses of the word "legacy," beautiful. Your new band is pretty young. What's nice is that, maybe not in any kind of intentional or conscious way, it seems like you've taken on the role of a mentor.

CC: Well, it's hard not to be. These young guys come up. When I first met Marcus, he was twelve years old. I gave him a hug. "When's your birthday, man?" I think a year later, Laurie brought him by The Blue Note when he was thirteen or so when I was playing with Roy. Roy said, "Man, have Marcus come and play with you. I want you to hear my grandson." He got up and he played and he knocked me out. He had such a deep feel. That was when he was thirteen. It's hard not to be a mentor. There's a little young drummer named Kojo who's now, I think, eight years old, who is the son of Antoine Roney. Antoine is Wallace Roney's brother. I met Kojo about a year ago and he came down to The Blue Note with his dad and there he is. Kojo and I talked to each other on email. He sends me the stuff that he does and it knocks me out, absolutely inspires me. It goes both ways. There's the mentoring idea of I'm the old guy, I've been around; but these young guys come with a fresh viewpoint. They may not have studied or know the history of this or that, but they come at it, they have a way in, and I get inspired by that.

MR: Do you see differences between the younger folks coming into it now and younger folks from the past decades? In other words, do you think this generation is any more inspired or gifted than others?

CC: I don't know. I know that the act of making music and creating art is ancient, the only thing that differentiates it generation after generation is styles. The way you dress, the instruments you play, what rhythms. The act of creation and the emergence in it is the same. It's that rush of recognition of one another as musicians where you can see that this guy is really in. He's very interested in what he's doing and you know that he's picked up on that flow. That part of it remains the same. Of course, the differences are cultural. To use a word from another subject, they're topographical. They're there, you know what I mean?

MR: Yeah. When you were incorporating these guys into your songs and into the new group and doing whatever degree of improvisation plus structure, did you watch them grow as musicians? Did you notice them go from point A to point G?

CC: I tell you, it's a thrill. It's an absolute thrill to see that because one of the points about working with real younger guys who know me and I don't know them so well is they come humble. "Oh, Chick, we're working with Chick now." That's okay, but I want it on an even field, so it takes a little bit for that to blow off. There's a little reticence at first, but that goes real quick when they see that we can hang together and they stop noticing the white hairs on my head. Then they really take off. We've been playing a lot of gigs this year and I wish you could hear the band from the record now. The band is like burning. We've got a new bass player and I have since added a percussionist to the band who I really love who works great with Marcus. They're creating some rhythms that have me all inspired to write the next album. So I'm very, very excited about what's happening with the band.

MR: So this is moving forward? You might say this is a "forever," excuse the pun, kind of thing?

CC: Yeah, yeah, it's going to keep going for sure. We're already booking gigs next year, I'm already toying with different ideas. As soon as I get off the road, I'm going to start writing some new music. We're thoroughly in touch, so yeah, it's going to keep going.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

CC: Well, gee... I mean, the advice is always pretty much the same whether they're new or old. When I'm asked for advice, I usually try to explain that advice is real cheap, you know? It's kind of true, because there's a guy there giving advice and he's saying, "I think you should do this" or "I think it would be better if you do this" or "it's more important to do this," and so forth and it's easy to do that. You can sit there and pontificate all day, and then it's the guy who you just told who has to be the one to do something and take responsibility for his own actions, you know what I mean? That's why advice is cheap. I always just encourage--especially young musicians--to trust their own judgment. That's what I always say to them. The only strength and joy they're ever going to have in creating their music and their musical styles and whatever else they do in music is going to be when they do what they love to do and what their own particular tastes are. It doesn't mean to become a loner. It means the final decision of what you play and what you choose to do and how you choose to involve yourself into the musical culture has to be your own choice and up to you and what you love. All of our musical heroes--I would think, the artists who have stayed there through the decades and who others look up to--that's what they do. Every one of my musical heroes, that's what they have done. That's what I try to do. So that's the advice I give; just think for yourself and create your own music and use your own judgment on things.

MR: Great answer, thanks. Chick, you are a musical hero to many people and I'm afraid to say that you're also an icon. How do you feel about being that person?

CC: I try and take it as it comes. It's very uncomfortable to look at myself and to think about myself, so I don't do it. But when it comes my way, I'm happy that a positive effect has been created and it encourages me to just keep on doing what I'm doing, which is making music.

MR: And what do you think of the state of jazz now?

CC: Oh, I'm no commentator on that. I can tell you one thing that's an intelligent thing. I travel a lot. I travel constantly and I get to meet a lot of local guys. I hear new bands come around, musicians are all constantly giving me their CDs with their new works and I try to listen, sometimes, as much as I can. I can say one thing, that the creative urge and the creativity in jazz or whatever you want to call creative music that comes from jazz, jazz music, is very, very alive. It's very there and it's very strong. The young musicians have universes of new ideas constantly coming. It's there. That's the state of things. The thing is, and it's always been this way, is that the commercial media doesn't show that. The commercial media will only show certain parts, and you kind of really have to dig to lock into that flow. That's why you have to go to some of the bigger cities--New York City or London or Paris--and go to the little clubs, because you can search YouTube and find some pretty wild stuff. But the creative spirit is definitely alive and well in our world.

MR: What's left that you want to achieve?

CC: I'm just on a continuance thing...I just want to continue. In terms of creativity, you know, there is no beginning or end or place where it's over. You're a free spirit, you have the choice to say, "Well I'm done with this, I'm not going to become a painter, I'm not going to become a ceramic artist, music is done for me now," but that's not true in my case. To me, I've just kind of scratched the tip of the iceberg. I've realized over these past couple of years that I want to become a pianist. I want to play the piano better. It takes practice to do that. In the life that I lead, it's interesting to try to cop practice time. So I'm sitting in my little room in Albuquerque and I have my little Yamaha 88-key piano that I carry around with me to practice. I'm working on different things, and that's the tip of the iceberg for me. There's lots left to do and there's lots always to do. It's just a matter of being healthy and up to be there and do it.

MR: Sweet. Thanks for your time, Chick. I hope to interview you for your next project, whatever that is.

CC: Sure, okay man. You're quite welcome to and I appreciate your interest and enthusiasm.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

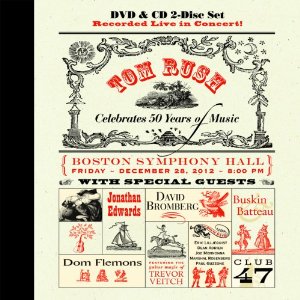

A Conversation with Tom Rush

Mike Ragogna: Celebrates Fifty Years Of Music is the album, Tom Rush is the artist and the man. Tom the artist and man, how are you?

Tom Rush: I'm doing well, how are you?

MR: I'm also doing well, thank you. You have a new album celebrating fifty years of music. I can't believe it's fifty years. What is all that about?

TR: I don't know! I don't know how that happened. It came out of nowhere.

MR: Before we get into the album can we talk about the early days, just to teach those one or two people who don't remember when you hit the music scene?

TR: Well, I was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, attending Harvard and there was a very vibrant, active coffehouse folk music scene going on. I'd already decided that I loved folk music through the work of Josh White and people like Odetta and The Kingston Trio. So I got sucked right into the coffeehouse scene and pretty soon was playing on a regular basis at a couple of different clubs and neglecting my studies, needless to say. From there, I started traveling a little bit outside of the greater Boston area, a little bit further and a little bit further, and it's been downhill ever since.

MR: [laughs] No, I'd say your popularity peaked pretty high and you've been maintaining that solid peak ever since, sir! Okay, you recorded this live album in Boston Symphony Hall. Did you play Boston Symphony Hall in the early days?

TR: Yes, I had. I played there several times. Back in the early eighties, I actually started a string of shows in between Christmas and New Year's that became the prototype of The Club 47 concerts. The Club 47 was one of the main coffeehouses in the Cambridge area and kind of the flagship of the fleet. I named a concert series after them wherein I put together some well-known artists as well as some newcomers. This past December, the subject of the CD and DVD set, was one of those shows.

MR: You had some interesting guests on here. You had Jonathan Edwards, mister sunshine himself, and Buskin & Batteau, who I will always remember as Pierce Arrow, and you also had Mr. "Carolina Chocolate Drops," Dom Flemons.

TR: Dom Flemons...and David Bromberg was there as well.

MR: And David Bromberg, another one of my favorites. These are all personal friends of yours from over the years. You've played with all of these people in the past, right?

TR: Yeah, Buskin & Batteau were my backup band for a while. Dom Flemons is the new face who I'd never met before, but the rest of the guys were old buddies of mine.

MR: Tom, while your music is very much rooted in the folk and singer-songwriter genres, your vocals so lend themselves to country. Over the years, were you ever encouraged to focus more on having a country career over the folk career?

TR: I've always loved a lot of different kinds of music. I think it's one of the things that was hot about me in the Cambridge scene, because almost everybody else was a specialist. People did nothing but Woody Guthrie or nothing but Delta Blues or nothing but jug band music, but I did a little of this and a little of that. I've always loved country music but I've never really been inclined to try to focus on it to the exclusion of other stuff.

MR: The material on your album represents different parts of your career. "Child's Song," "No Regrets," "Driving Wheel" and, of course, "Urge For Going," perfectly represent what was going on in the singer-songwriter field. Your recordings shone a light on a lot of great up-and-coming songwriters such as Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, James Taylor, et cetera. What was that whole scene like? Did you feel, at the time, like you were introducing important talent as you were recording those songs?

TR: To tell you the truth, I was just looking for good songs. I was not thinking in terms of discovering or giving a boost to new talent, although it seems to have worked out that way. I was just looking for a track for an album. I was a couple of years overdue, I was desperate for songs, and I found some good ones by these fabulous writers.

MR: I'm imagining that over the years, you've crossed paths with some of them. Did they ever express their feelings about your versions?

TR: James Taylor's been very vocal about my role in his career. Joni and Jackson, I see once in a while, and we're friends. We don't go bowling all the time, but we're friendly.

MR: [laughs] "Child's Song" by Murray McLauchlan, that song really resonated with me at the time because I discovered it as I was leaving my home. A lot of this material must resonate with you in deep ways, too, right?

TR: Oh yeah, absolutely. When I first learned "Child's Song," it was such an emotional song that I couldn't perform it because I'd burst into tears halfway through. I know a lot of kids would play that song for their parents as they were out the door. Now I still play it and now all the mothers cry.

MR: [laughs] "No Regrets" is a song you've recorded a couple of times, but my favorite version of it was on the album Tom Rush on Columbia. That album is probably my favorite, with songs like "Indian Woman From Wichita" and "Claim On Me," things like that, that to this day, still pop into my head. Your fans must be telling you things like this all the time, especially with songs like "Child's Song." At first, you couldn't get through singing "Child's Song" live, now imagine the people that are hearing it in the audience. They must have a very emotional reaction as well. My real question here is, do you see how your material resonates with your fans?

TR: I think so. If it wasn't resonating, I probably wouldn't still be in business on a pragmatic level. But yes, I think the key is to find really good sounds and then if you do them properly and just get out the way, people will respond to them.

MR: When you're writing a song these days, is it a different process than when you first started? It's fifty years later, so are you conscious about what may have changed in your process between then and now?

TR: I'm probably too close to it to give you a coherent answer. I don't write anywhere near enough; I should be writing a lot more. But one of the things that I've learned is to not try to push the song into existence. It's more of trying to pull the song out of the shadows. I'm not good at writing songs to order. Either they come of their own accord or they don't.

MR: Great answer. What do you think when you look at the folk scene these days?

TR: I think there's a very diverse singer-songwriter scene going on. To me, the word "folk" means traditional material, and there is a lot of that as well, that's also a vibrant scene. But what most people mean when they say "folk" is the earlier singer-songwriter side of things, the acoustic singer-songwriter side of things. There's a lot of wonderful talent out there.

MR: When you look at the young talent that are coming up, are you looking at them and going, "Hmm, if they tweaked this or that, then that song would be better?" You have fifty years behind you, you absolutely have the ability to be a mentor.

TR: Well, I wouldn't dream of trying to coach anybody in their songwriting, but in terms of stage presentation, I think I might feel like coaching people a little bit.

MR: What is your advice to new artists?

TR: Play in front of audiences as much as you possibly can. You'll learn more in thirty minutes in front of an audience than you will in thirty days rehearsing in a garage.

MR: Wow. That's a song right there! That's excellent. What do you think about your body of work when you look at it now? All these albums, classics that fans play to this day. I'm not sure if you listen to your own material, a lot of artists don't do that.

TR: I don't.

MR: Do you have any thoughts about your career?

TR: I wish I'd written a lot more songs. Other than that, I can't complain too much.

MR: Yeah, although it does seem that a lot of great material came through you or came your way.

TR: Well, I think, yeah, and when I'm putting together a setlist or a song list for an album, I don't much care who wrote the songs, I just try to do the best songs I can find and do them as well as I can, so I'm quite comfortable doing other peoples' material.

MR: Where do you picture Tom Rush this time next year? What are your upcoming goals?

TR: Oh, I've got about three or four albums in mind that I'd like to make. Different projects. The fact that there are so many different ones is what's throwing me down. I'm working on a book along with everybody else. I've actually been asked to write an autobiography and I keep trying, but it keeps veering off into different directions, one of which is a manual for people who'd like to be performers.

MR: Thus, advice for new artists.

TR: Exactly.

MR: All right, well I appreciate your time, Tom. Thank you very much and all the best. I really do love your material.

TR: Thank you so much.

MR: Be good, take care, have a great day.

TR: I look forward to speaking with you again in the future.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne