A Conversation with Al Di Meola

Mike Ragogna: Al, you're the recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Miles Davis Award. What was your reaction when you found out?

Al Di Meola: Well, I didn't expect it. It was a complete surprise. I'm very honored to be in this really reputable and legendary company, from the past recipients that I've seen. It really is a nice feeling to be honored for my whole catalog of past work. It's really an acknowledgement of my entire career. It's nice that they notice that. I would've expected it from Berklee College of Music, my alma mater. I wouldn't expected it from another country but I was very happy to get it.

MR: It's interesting that even though jazz seems to be America's gift to the world, in the US, it doesn't compete with pop culturally.

ADM: Yeah, I have far more acknowledgement from places like Germany, Austria, places overseas than in the United States. It's always been like that. I don't know, I think they have a hipper system over there when it comes to playing. There's a thing called The Marshall Plan where after World War II we had to agree to fund the arts of foreign musicians and that never stopped. There aren't so many private promoters putting on shows; they get funding. There's still this allure about anything to do with American jazz or classical. If you're American there's more want for you in any of the festivals. There's more allure for that. The audience has grown as a result, because they really appreciate it. In the states more often it's private promoters who'd rather not risk their own money. There isn't as much funding going into any derivative of jazz whether it be fusion or whatever. Classical is solely dependent on funding, otherwise there'd be no classical shows. We have to rely on private promoters in the States who are very cheap.

MR: It seems like smooth jazz ended up being the commercial default for US jazz for a while.

ADM: Smooth jazz kind of put a damper on things for a while; that's why I shifted my attention to Europe primarily. In fact I have a home over there because I'm working there every month. It's been so long since I've played the states that I said, "Now I'm gonna have to do some radical and come back," maybe even return to the roots, those early records that whoever's left of my fans can grasp on to, those early electric records. So after a lot of self-convincing I decided to give it a go. It may be the last time, but I wanted to see what it felt like. We've already done three legs of the tour and I'm planning another one in October. Of course, it's fun, and the audience reaction is fantastic. Had I come over here and done some of the acoustic things that they really appreciate in Europe it would've been a quarter of the audience. It just wouldn't have been the same thing. Now I'm balancing two different types of acts, my acoustic act in Europe and my electric group in America, more focusing on the hits of the early years.

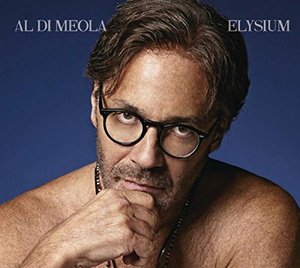

MR: As you're touring the older material and what's been recorded for Elysium--which feels, at times, like a nod to Return To Forever material--what are your thoughts about the merging of these bodies of work?

ADM: A lot of the older material had us dig out those charts from decades ago. Some of it came right back and some of it was foreign to me. It was really strange. At the last moment, before the first tour, right before I was ready to go in and record what was to be an acoustic record called Elysium a friend came over with his Les Paul and his pedal board of all these sounds and he created this really amazing concoction of different pedals. Not that I was into playing the electric again, but then I started fooling around with the sounds and then playing some of the new music with it and I go, "Man, this actually works great! Since I'm doing the electric tour maybe I should tie the two in." So that's what I did, I recorded the basic tracks with the acoustic guitar but then the counterpoint melodies and improvisations were done on a Les Paul. It kind of ties in, it's a 2015 version of Elegant Gypsy, that's where I'm at now as a composer, but it ties in that sound that people remember.

MR: Did you find a bridge between the pedal board and your current sound?

ADM: There's all kinds of different sounds, delays. There had to be like twenty different variations of sound that I found to be interesting. The electric guitar is such an amazing, expressive thing unto itself, it's so different from the acoustic. It was a bridge: from the past to the future. I made it work. I made it work with the new music where I didn't think it would when I wrote it. Not all of the album is electric of course, I kept some of it in its original form, but some of it worked so well that I was surprised. It's like going back home again. We worked some of that music into the show even though the show is bent towards the Elegant Gypsy period in the beginning. I still have to play some of the new music and let the audience know I'm still writing music that's an extension of where it began. I find the new music more interesting to me than the old music, but the whole theme of the tour, which really created a giant buzz, was that I was doing the music from a period the audience thought I had left forever.

MR: What connects Elysium to the earlier records?

ADM: The actual sound of the guitar is the only thing you can connect to the early years musically. I think it's far more advanced. I have more artistic enjoyment doing that.

MR: Was there anything you did differently while recording this album?

ADM: Oh, absolutely. I recorded a lot of them in my house. I have this really large gallery with a triple-high ceiling that was never used for recording. It looks like the size of a big studio room like The Power Station or Abbey Road, that kind of ceiling height that's perfect for recording drums and a whole band. I had the affordability to do that because I had gone through a divorce, so the writing period was very interesting. While going through that horrible period, writing was my salvation, my meditation. It kept me sane. I went from the dark to the light during the writing of that record. But when I went through it and I got the house back I decided, "Hey, you know what? I can record anywhere in the house right now." So we utilized both the studio downstairs, the control room, one of the side rooms, and also upstairs. We had snakes running all over the house. The whole house became a studio, it was totally cool.

MR: Was that process of going from darkness into light also the process for each of these recordings?

ADM: No, except for The Beatles tribute, All Your Life. That was the beginning of the torture. It's a good thing I thought about doing that, because it was so exciting and so inspiring to be at Abbey Road where they created those masterpieces and do something in my own way in the space in which they did those famous recordings. It helped me take my mind off of what I was going through.

MR: I'm sorry you went through any of it. Was there a track that gave you a sense of accomplishment?

ADM: I'm really proud of the compositions. It was a very long period of going through what I was going through, and the only thing I could do was compose. Well, whatever was coming out of me, I just wrote it down, even if it didn't make any sense. I think there's a lot of depth in a lot of the music that is different from the early albums. I was artistically very happy with the development. It was something I needed to do, especially after doing The Beatles tribute. I needed to get back to taking my writing to the next level and really have an appeal to fellow musicians and guitar players. That was my hopeful intent. But then when I went into the rehearsals for The Elegant Gypsy And More, I realized, "Oh my God, how simple this music was compared to were I've grown." By the way, I felt that way about RTF, too, when we did that reunion tour in 2008. I was like, "Man!" When I was nineteen and I joined RTF, it was challenging. It was like, "Woof, this is big leagues." When we did the reunion tour in 2008--and we're talking like thirty-five years later--to me, it was a piece of cake. It was nothing like the music I do in Europe with my acoustic group, which is far harder.

MR: I imagine the demand of keeping up with Chick and the gang was probably huge for a nineteen-year-old.

ADM: Oh yeah, you had to grow up fast. Luckily it was a composition band as well as a chops band, and I'm glad it was. It wasn't just a chops band like Mahavishnu [Orchestra]. You don't remember them so much for the songs as for all the playing. RTF was a big influence on my very early development. There was a lot of substance to the composition.

MR: How do you feel your improvisation chops have grown over the years?

ADM: It's grown. There were some great improvisers in RTF, and when you're with other improvisers you grow and learn how to converse. You have to have your chops together in order to play the written music as well, but you have to improvise in between. If you can't improvise you'll never be able to last with a group like that. And then it went to another level with Paco and John. We were like three gladiators fighting. You had to be better than ever because it was really a technique duel to the finish.

MR: Do you think all that has significantly improved your game?

ADM: Of course, big time. Here's the thing that guitarists that don't have the technical ability might be snide and say a sarcastic remark about anything like that: If you have the inspiration and you hear it in your head and then you go and try to play it and it comes out sloppy, there is nothing worse. A burst of inspiration the provides you to exhibit that kind of thing, you have to have the ability, chops-wise, to execute cleanly. A lot of guys might cheat by picking a note and carrying on or this thing called "sweet picking," which is awful.

MR: How hard are you on yourself? What happens when you don't quite get to "the moment"?

ADM: Jesus, it's constant practice. You have to just keep practicing. You don't get to a point where you go, "Oh, I've got it, I don't need to play it. A lot of the music I've written is a practice unto itself. I have to keep practicing it to get it cleaner and up the tempos. What if the tempo does go up? Are you able to execute it? Then there's a whole other level which is something that i do naturally and which has become my style, I syncopate the hell out of everything. Syncopation has really become my stamp. If you can syncopate with good technique where the listener is totally locked in the time and you're syncopating off of the time and the quarter note doesn't move then you've got hypnosis. Then you've got the people totally melting into the music, and that's important. If the time is all over the place your quarter notes are all over and you syncopate against bad timing, that's a tragedy.

That's something that true Latin players totally understand. You're either born with this thing or not. It's not something you can learn. You can learn harmony, you can learn every other aspect of music, but you can't learn the subject that I'm talking about. There are a lot of great Latin players, Chick [Corea] included, and Gonzalo Rubalcaba, a lot of great pianists have this kind of thing, or a drummer like Steve Gadd has got tremendous sensibility of syncopation off the clavé. If you have this ability then you can do all of these great things rhythmically, syncopated-wise. It's all part of having good technique, but what you can do with rhythm is far more interesting. It is the key element before everything. It's even more important than melody. What draws people in is the rhythmic side of music.

MR: Do you think syncopation is relative and ties into nature's rhythm?

ADM: We all have a heartbeat. We all have something that's beating inside of us with some kind of pulse.

MR: Oh, that's nicely said.

ADM: There's times when that pulse increases. You could be looking at a gorgeous girl, or engaging in some kind of activity and there's that heartbeat. We naturally relate to the actual rhythm because we have natural rhythm in us. If you can connect to that--A lot the guys don't, so if I do clinics, even though they might have that pulse in the upper part of the body, they might not be able to transfer it to the bottom part of the body. I remember having a class of six hundred guitar players and I had them all tap their feet and then play a syncopation rhythm on the guitar. I watched the feet tap quarter notes and I asked them to play a syncopated rhythm and I watched every one of those times go up. I watched every foot go off of its time because the syncopation that's created by the upper part of the body affected the lower part. They all had bad timing.

MR: Do you think that's something that can get better with practice?

ADM: No. You're either born with it or you never will have it.

MR: But with more practice and exposure to various music and techniques, couldn't a player have that breakthrough and acquire it?

ADM: You'll never get that, but you'll get a lot of other stuff. There are so many aspects to music that it's not like you need this thing in order to make great music, or good music, or even bad music. You don't need to have this. It's just that if you have this extra element then what you can do with rhythm is mind boggling.

MR: Could that be one of your superpowers?

ADM: It's only something that I've come to appreciate in what I do in recent years. It's not something that I even knew I possessed early on, but as time went on it was the thing as early as 1977 or 1980 when I was doing stuff with Paco de Lucia, it's how we got along so well. He had that natural ability. It's the ability to feel the upbeat. Not everything has a downbeat, so the syncopation of the upbeat, without losing the quarter note downbeat is phenomenal. When we were playing rhythm together, or anything together, the sync factor was knockout. That was something I developed more and more because I was influenced by his flamenco way of doing that kind of thing, and he was into my Latin approach, which is more coming from the salsa side, but they're both the same feeling. Chick has that too, by the way, it's just that with RTF we never ever hooked-up. We never got close as playing partners. It was more of a band that didn't exemplify any of that element I'm talking about. It's too bad, but I had with Gonzalo Rubalcaba, the pianist. Unbelievable.

MR: From Paco, you picked up flamenco. Can you feel the influence of other jazz artists you've played with in your own music these days?

ADM: Well, sure. All of my influences, whether it be listening to the Beatles or playing with Paco who is a traditionalist flamenco player, or Chick who is a traditionalist jazz player. Somehow, aligning myself and having the influences of some of the best guys in each of those fields worked its way into my world. I had the good fortune of playing with them and having their influence surround me and getting to play with it, but I also had good taste before I met any of them, in terms of who my influences were prior to all that. Really what I do has always been a fusion of sorts. If someone says, "Oh, I love when you do that flamenco thing," well I don't really do that flamenco thing at all. It's just that there's influence of tango because of probably the most profound influence, Astor Piazzolla, the great tango composer and bandoneon player. That was even more than anything else.

There was a guy who I became friends with and he was a fan of my music before I'd ever heard any of his, but when he was alive he was really the modern Bach of classical tango music. What was so amazing about him that overrode any of the fusion heroes was the fact that he can write the most complex music but at the same time touch your heart where you feel like crying. It's amazing. It ran the whole gamut of emotions, but it also had interesting complexity. Fusion music and a lot of jazz had none of that. It had only the technical side of things, the cerebral attachment, but it was never really getting to the center of my heart. When I think about my early influences--It could be The Beatles--A lot of that music was very heartfelt, so it was the melodies that grabbed you. By having a Piazzolla influence it was tying in something that I grew up with, the beauty and simplicity of pop music, and where I had gone musically with fusion and being influenced by classical music and jazz and Latin and all of that sort.

MR: As someone who has taught as many players as you have, have you ever come across a student that made you think, "Man, this one's special"? And have you ever learned anything from a student?

ADM: No because they haven't done that much of it to have anything come to mind so quickly. The only cool story I can think of is this kid from the projects in Detroit. He came to my show recently in Toronto, this really big black kid from the projects who taught himself how to play this small-scale violin. He was dressed like he hadn't been to a store in ten years. You could tell he was not doing well at all. He comes backstage after the show, I found out he drove all the way from Detroit to Toronto to hear the electric band back in June. My percussionist said, "Man, you've got to hear this kid play." I said, "All right, give it a go." He plays me some of my music totally locked in time, and mind blowing lines. Totally clean. Impressive beyond belief. He just taught himself, growing up in an environment of crack houses and murder and all kinds of bad stuff. I just could not believe it. I said, "Man, we're done for the evening, what are you doing now?" He said, "Well, I'm driving back to Detroit." I said, "What?" I just reached into my pocket and grabbed a few hundred bucks. I said, "Take this money, meet me tomorrow in Montreal and you're going to play with us at the Montreal Jazz Festival."

I told the story to the audience; they loved it. And then the kid comes out and he plays and I'm telling you, this kid was jumping all over the stage, playing unbelievable stuff. Even the call and response. That's where you know you've got a guy that's got a natural killer talent. He's always got that down. You don't grow up and all of a sudden at fifty you have that. So he has an unbelievable ability to listen and hear and just knows instinctively when to stop and let the other person play and play off of the rhythm. And the timing factor, boy. If someone's got good timing, they're my friend. I wanted to hug him. I was watching, smiling, laughing, the audience shot up to their feet. They all got up on their feet and the applause would not stop. To me, that was a new discovery but so enlightening. I'm so happy that I'm able to do that. I asked him to join the band, he'll be on that October tour.

MR: That's a great story. Al, what advice do you have for new artists?

AD: For new artists? New artists have more challenges today than ever before. You might look on the one side that they have the availability to be heard and seen through the internet, but it's not like it was on the other hand. Record sales have completely come to a complete halt. It's over. Downloads are very minimal. New artists can barely keep their musical gig. They often have other jobs. Until streaming sites can pay these major record companies the money and the record companies in tern pay fifty percent to the artists, it's going to be very, very difficult for new artists to just do their art and not have to fall back on anything else. It's actually criminal what's going on between streaming sites and record companies. Streaming is a good idea, but artists need to be paid. Right now, they're getting paid probably one one hundredth of a penny on a play, which is totally insane.

Everyone is on the road because they found a loophole to get away with this, but not for long. Guys like me are fighting it, and we're going to keep fighting it until it changes. In those contracts that were signed years and years ago, there was never any provision for streaming because there was no such word as streaming. What they're doing is they've created a new royalty system unto themselves. It's hard for the artists to band together and fight something like this. We need more of the old school music attorneys that are no longer in the business. They're gone. When they were representing us back in the day, we were very protected by these guys. Now it's a matter of pointing out to the record companies, "You're going to have a problem with us." New musicians want to play their instruments; they want to make new music. But then they're not going to get paid.

MR: That's a good point. Now what if artists stop supplying labels with new product...I know, it's far-fetched. But that theoretically creates an environment of music fans needing to see an artist live, that being the new paradigm. of course, At the venue, fans naturally would buy downloads and physical product directly from the the artist with no middle entity.

ADM: Right. If you want to sell your product, you've got to sell it at the show. If you own your product then you don't have to share it with the record company because you paid to make it. But how many artists can pay to make their own record? Even though a lot of people are making it in their house and their friends will contribute for next to nothing. There's plenty of those records, but how many of them are going to sound like the great records from the days when the record industry was flourishing? When there were big budgets and you could craft your record and do a little production? I can't even make a record like that.

MR: True and we do have a continuing dumbing down of sound that's been happening for decades. And recording at a place as prestigious as Abbey Road isn't even a consideration for generations of young artists at this point.

ADM: And what a fortune it was to record! I recorded three songs and said, "I'm going to have to go back to New York and finish it in my studio. I tried, but the sound was one tenth as good as Abbey Road, so I was forced to go back. It was so high a level of sound quality that I didn't want to mismatch the other songs I was going to record to complete the record. The one thing that kept it sort of within the range of me not going broke was the fact that I didn't have anyone else on the record. If you started adding production and bringing in players and quadrupling costs it would be insane. What made the record unique was that it was primarily a solo acoustic record. If there's a part, I'm playing it. That's cool, I wanted to make it very different from The Beatles' approach anyway. Even though I was lured to do overdubs, "Man, I could put some strings on this part, I wish I could put some bass or some keyboard sounds," once you start doing that then you've opened up a can and all of a sudden that nine days turns into easily three or four weeks.

MR: Al, I'm a big Paul Simon fan and you played guitar on the track "Allergies" from his Hearts And Bones album.

ADM: That was supposed to be the return to Simon & Garfunkel. Art Garfunkel sang on every song, but the two of them did not get along. That record could have been a monster. It was actually better than Graceland. I listened to Graceland a few times recently and it's good; it had a cool vibe with the African thing and it was a very smart idea. But Hearts And Bones was great writing. With Art on there, that could've gone double platinum. It was still within that space of record company stability when you could sell a ton of records. I think that would've become a big comeback record for them.

MR: I agree and songs from that album such as "Rene and Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After The War" could've become instant Simon & Garfunkel classics.

ADM: I was supposed to be on that one. I still have the music he sent me for it here. I was on "Allergies," but I just couldn't make "Rene And Georgette Magritte..." work so Paul wound up not using my part. I was just happy to be on anything of his because I was a fan of both of them. Those early records were great.

MR: Yeah, they sure were. Though I especially like the early albums, I still enjoy almost all of Paul's albums as well as Art Garfunkel's Angel Clare album. It included his biggest hit "All I Know," which was written by Jimmy Webb. It also featured singles like the Van Morrison Moondance leftover, "I Shall Sing," and Paul Williams' "Traveling Boy." But I think there was a magic and cultural importance about Simon & Garfunkel that has never been duplicated since.

ADM: They should've done their solo records but stayed together as a duo. It's like Chick. He always keeps the nucleus together because it's so powerful, but then you can go off and do your own solo stuff in and around it. The Eagles do that and they're cleaning up. The Rolling Stones do that. Keith's got a new record coming up, but the Stones are the nucleus. It's just a totally smart thing to do.

MR: Where do you see your creative career heading? Do you have a game plan?

ADM: There's not a game plan. Where it could go is I have some other material, you could call it leftover from the last record, that I would make even more electric. If you've noticed there's very little bass on Elysium because it was originally supposed to be an acoustic guitar record, which doesn't really have necessity for any bass parts. The complexity of the music was enough that it didn't need another counterpoint, basically. If I complete this other music, I would add in the bass so that if I continued the electric band could play this stuff as well. That's one project I could do. Or I could do a second Piazzolla tribute record as well. I've always wanted to do a pop record, in my way. All the cool songs that I grew up with that I like and just pick like fifteen of them and do remakes. But I don't know which one I'll do first.

MR: I'm curious, has Jersey had any influence on your creativity?

ADM: Jersey was a tremendously beneficial place geographically to grow up. My proximity to New York was so great, so we would constantly go check out bands, whether it was Phil Maurice down in the village--I saw everybody you could imagine and all of it was tremendous inspiration for my development as a musician. You could see some great stuff at jazz clubs any night of the week. The Latin clubs I used to hang out in quite a lot, it all paid off to have such close proximity and a great teacher in the very, very beginning and then going to Berklee. It all worked out. Had I grown up in Montana or Idaho or Kansas, maybe not.

MR: Your Elegant Gypsy album is considered one of jazz's classic albums.

ADM: That's why I had to do it again. It's super simple next to the writing that I've been doing the past twenty years, but simple can be great! It doesn't have to be viewed as simple and not happening. In the minds of these people it's what they remember. If you go to see the Stones, you don't want to hear any of their new s**t, trust me. not at all. You don't want to hear any of the new shit of any band. The Who, or whoever's out on the road. If Led Zeppelin got back together would you really want to hear their new stuff? You want to hear what you know.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

******************************

NEMES' "WRONG" EXCLUSIVE

According to the Nemes' gang...

Nemes (pronounced knee-miss) is a Boston-based 'aggressive folk-rock' group who are releasing their new video for "Wrong." The video was created and edited entirely by the band themselves over the course of 24 hours. The loose vibe, and quick cameos from rising stars Jon Hamm and Taylor Swift work together to aid the self-deprecating rock-folk soundtrack.

According to Nemes' singer and guitarist Dave Anthony...

"I kind of felt like everything I wanted to say was already in the lyrics but It's really cool to see people responding to it, and having someone asking about how this song came about. I was working 10 hours a day landscaping and anyone who has a fifty hour work week knows how physically draining it can be. I was burning the candle at both ends and I suppose it showed because everyone said that to me all the time. I would get up at 7am, work until 5, shower, drive an hour out to Boston, Taunton, Weymouth, or where ever we were gigging, play a show with the band, drive back for 1 or 2 or 3 and then get up at 7 the next day and do it all over again.

"I did this for about a year and a half. I think it was around this time that the song started to take form. I was getting into fights with everyone in the band, and the only escape I had from the exhausting physical labor was to make melodies in my mind all day, and since I was doing simple boring repetitive tasks, I would come up with repetitive, catchy little melodies that I thought were fun to keep singing over and over in my head.

"I didn't see it coming but my boss had to lay me off. I think he knew that my heart was fully in love with music and I couldn't keep up the schedule so he walked me through all the things I had done wrong that week, I tried my hardest to be good at the job but my heart just wasn't in it and we both knew that... I felt like crying at that point. He was right about it, all of it, but it hurt to hear. I wanted to make everyone happy and do well on all fronts, but the band was going through rough times, I was performing very sloppily... The muscles in my arms had been so overworked that I could barely play power chords anymore. It was embarrassing, I had let everyone down.

"It was a very sad place to be in when I wrote that song, but I think I needed to go there because everyone feels like that sometimes. The song got whittled down to an actual form in the coming months after I had left the world of landscaping and started to do music as a full time career. The lyrics all kind of poured out one day and I think Alex helped me reign in the lines to keep it concise and catchy and not too meandering. I think after that Josh and Chris jumped in and jammed on it and we all had a blast flushing it out. It was extremely cathartic to get it out.

"The track is an expression of the singer's complete lack of ability to do anything correctly in his life. He has little to no faith in himself and like anyone else who suffers from similar feelings, he one day just accepted that there is no chance of getting things right and decided to celebrate doing things incorrectly, rather than chastising himself for this, he has simply come to expect whatever happens, the result is a no holds barred, celebration of being born on the wrong side of the tracks."

For more information: http://www.nemesband.com

******************************

RUNNER OF THE WOODS' "EASY ON ME" EXCLUSIVE

According to Runner Of The Woods' Nick Beaudoing...

"In the video for 'Easy On Me,' I wanted the natural beauty of Tennessee to do the talking. When you spend hours each day staring at computer screens, a visit to the great outdoors is rejuvenating. Being on or near a lake makes you think differently. You can get meditative and let your mind drift to memories both good and bad. Our bass player, Craig Aspen, shot the video at his cabin near Center Hill Lake in Tennessee. Unlike most of the muddy reservoirs down here, the water is absolutely clear--it reminds me of Canadian lakes from the family vacations of my youth. We also wanted someone to play the part of an ex-girlfriend, and actress Kate Meushaw fit the bill perfectly. She and I never appear in the same frame until the scene where we argue, and that moment is really all the backstory you need. I think most of us like the idea that people who drift out of your life will think well of you, in spite of everything."

*****************************

A Conversation with Reuben Hollebon

Mike Ragogna: Reuben, you've built part of your story by engineering for acts like Basement Jaxx, Courtney Barnett and even The London Symphony Orchestra. Where does performing and recording as an artist yourself fit into your bigger creative picture?

Reuben Hollebon: Right now it's pretty much everything. I don't rule out working on other music. I've been shaping up an EP for a good friend this week; however, my own music does comes first. I have a strong desire to stay involved in helping others. It would be great to move through the different disciplines. It's not easy, they all take practice, and I've great admiration for mixing engineers and producers who focus solely on their craft.

MR: What inspired you mostly to pursue creating music and engineering/mixing/producing?

RH: I enjoy creation, in all forms, and it is needed for anyone to be fulfilled. Working in a studio comes naturally. It's treating music like a water flow; at least it was before computers ruled the day. Initially you attempt to recreate the pure form you hear. Once that's achieved, you can get creative or allow someone else to do so. There are many thing I'd like to do, but this is what I do right now.

MR: Who influenced you musically? Who are some of your favorite current artists?

RH: Many artists have been seminal for me, each bringing their own qualities. Devendra Barnhart reinforced the joy, Radiohead the majesty, Tom Waits the story, and Arvo Pärt brings me back to music if the desire ever slips. Currently, I still hope Jai Paul will release a full record; Villagers are on form, and I just picked up Asunder, Sweet and Other Distress by Godspeed You! Black Emperor.

MR: So far, you released the tracks "Faces," "Seven" and "Clutch." How did you create these recordings and write the songs?

RH: "Seven" and "Clutch" were from my first EP that I put out in Europe, that followed with an ad hoc tour. It was a dawning of myself as an artist, and I couldn't release it fast enough. I moved enough copies to cover getting to the shows, not many of the original batch are left. They were poetic ideas painted in songs. When the intent feels that strong there's not a lot of other work to do. "Faces" was an opportunity for me to take an idea and work it hard with two friends I admire greatly, particularly as producers. We conspired for two days and were pretty near finished. I've reworked it a little for the LP but it was very close to the first print.

MR: What gears shift when you're working with other artists as opposed to creating your own material?

RH: It's not dissimilar, some of the reference points are altered and no longer your own. If I can keep the rails on for someone else and help where requested, then it's a good day.

MR: You're performing a series of concerts soon that you list on your Facebook page. So what is a Reuben Hollebon concert experience like?

RH: It's me offering an invitation to share a few melodies and words. I enjoy it; however, I have a great fear for the stage. Breaking through the nervous energy doesn't happen alone, it takes one or many people watching. It's one of the few moments presented to understand what a song is. The same thing needs to happen whilst recording.

MR: Musically, do you have a mission?

RH: This talk gets bandied about in the late hours by the various producers and musicians I work with. There is a want to do something of note, but I can't start to create a song with that intention. The clearest outcome is to continue making music in the best way, both live and in the studio. I have a vague idea, but I hope to learn what that really is.

MR: What's moves you, what drives you and what would make you the most happy as an artist?

RH: When I wake, writing songs and performing feel as important as eating breakfast. It's part of me, it may always be. There's room for improvement but I stay content with this process, and if I can keep that up all is good.

MR: How about as an engineer/producer?

RH: Here you take the same thoughts, but note they have to function for someone else's intent. When involved, particularly from the beginning, you get to hear a great song, and then be part of the translation to a great performance and record. The part I play doesn't matter as much as the outcome, so I try to not to interfere unless asked for. As a producer there is a little more weight on the execution of a record with associated expectations.

MR: What's been the best studio or personal experience while working with other acts?

RH: I've been humbled by many of them, the players are my favourite, the kind of musician that won't stop unless they have too. There's been a wonderful reduction of the mystery and insight into the workings of a record and soundtrack; however this hasn't taken away from the brilliance.

MR: When you look at the music scene now, what trends do you see coming and which will you embrace or avoid?

RH: It's vibrant and sprawling at the moment, hard to hold on to all the edges. For me, the records I like are returning to performance, the problem being modern techniques can push away from this. 'Vintage' gear is great; however, the old recording methods are what makes amazing music. I've tried to keep to this in the studio, but I won't deny a bit of trickery, sound design and automated mixing. The majority of my LP is formed from single take recordings of the separate tracks. Sounds are addictive, but songs are the things that last.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

RH: You need to take all the advice you can get, and then keenly sift through it. It's the same as advice for life, it needs to be applicable for yourself.

MR: What will Reuben Hollebon absolutely have accomplished by five years from now?

RH: If I'm still able to make music then I'll be content, and no one but myself is capable of stopping that. I have already a lists of things I want to accomplish on stage and in the studio. Performing with other musicians would be ideal. Where I live, who I am, that's not for telling yet, I'm not even aware myself.