"What's Sex Got To Do With It" by Jody Joldersma, reprinted here with her permission

Today was bright white, as I've come to appreciate about Seattle. I feared dark days. Instead, the ocean near the Paccar Pavilion was lit up by a bar of pale sparkle across the far side of what water we could see as Charlotte Austin, the editor of the Better Bombshell anthology, stood with the wind whipping her blonde hair, counting the pillars to be wrapped with christmas lights for the book's release party on February 14th.

The last time I was in Seattle, my system was in shock. The sky winked. My muscles flicked, trembled, and with any movement of my body, spasmed in ways so painful, I'd have to stop laughing, stop reaching. Every interaction ended with spirals of anxiety that only had room for one. I knew something was wrong, but not what; the PTS diagnosis wouldn't come down the pike until I finally got health care that fall in Indiana. To return to the setting of such hopelesness--Seattle, the long green bodies of buses tipping and climbing, the bright bar of water, magnolia blossoms and rain-soaked air -- is a test of my restored spirit. Less than three years ago, I left Seattle for the doctor in California I had known for a decade. He took one look at me, quaking and swollen and sure I couldn't stay wherever I was, whoever I was, and said gently, "I think your neurotransmitters are damaged."

Less than a year later, I was in Africa, sitting in a soiled room in a slum of Nairobi with four girls from Congo: refugees, orphaned, carrying memories of slaughtered family members, and, as I would learn, unthinkable violations. The group grew to six, and the girls began to respond to my introduction of the idea of "safe space" in our arts workshop: they named themselves the Survival Girls and started to voice their shame and their anger to each other, creating theater pieces about rape that brought grown men to tears. They started to confide in me: "I can't control my thoughts. I can't stop replaying what happened. I'm afraid I'll never be like the other girls. I can't stay where I am, I keep going back." To each of them, quaking in my arms, in spite of how little my trauma was compard to theirs and how little I knew of God, I said: "I know what you mean, and what is happening is normal. Your heart works properly, and your mind will come back. There are some things I can teach you to help. You are not tainted and not dirty: you are perfect in my eyes, and in the eyes of God."

"Lion and the Lamb" by Jody Joldersma, reprinted here with her permission

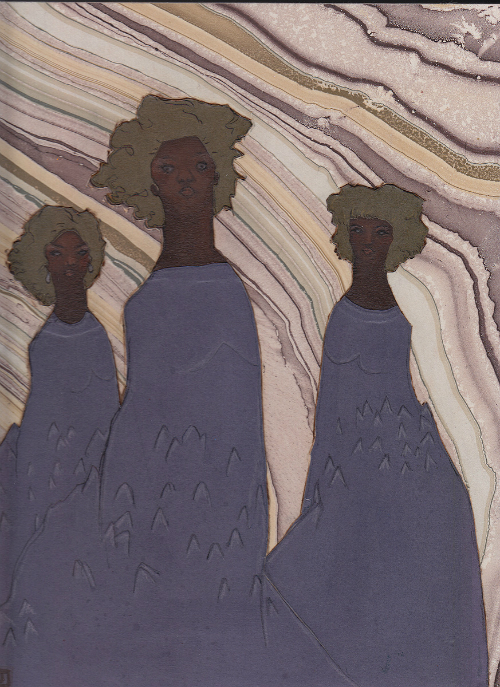

This isn't a story of how I am the girls' role model: it's a story of how they are mine. The sun inside them, and the alchemy of their will to turn the most unthinkable violence into the strongest singing voice, the broadest smile, must have something to do with why the Survival Girls stayed together independently, doubled in membership, won contests and contracts to perform, continue to this day to comfort other girls. Here in Seattle, writers from Roxane Gay to Dave Barry and artists from Deborah Scott to Chris Sheridan collaborated in pairs on words and images about what it means to redefine the female role model for The Better Bombshell. If it weren't for the artist I was paired with, my writing about the Survival Girls wouldn't have seen the light of day. Jody Joldersma, a slender, kind, attentive woman I didn't meet in person until yesterday, surmounted the impossible task of creating paintings that honored the girls' travails and spectacular spirits. When I saw the paintings, I didn't just cry; I knew that Jody could see the girls, which visibility is the only morally sound reason I have for putting pen to paper about them.

Holding our coffees shyly, runners loping around Greenlake out the window, Jody and I chatted about the girls, about Jody's paintings (Jody is the only Better Bombshell contributor to identify in her bio as a 'feminist', and we wondered about what a dirty term it has become), about Anne-Marie Slaughter's re-ignition of the furor around what it means for women to have it all. Jody, one of the most gentle people I have ever met, whose paintings disturb and upset notions of sex and gender with twists on "two biases together," said something that resonated with me as the best description of the Survival Girls' strength yet: "To have it all, internally, is to keep an open heart, without giving any ins to those who would drain us."

"Sing the Songs" by Jody Joldersma, from the Better Bombshell anthology, reprinted here with her permission

And that's what I believe the Survival Girls continue to do. It's the balance their hearts have mastered. The war tore their hearts open, their bodies open, their families open. But they learned to create a wheel with their human presence for each other: what they lose through those gaps, they transform into performance, and enacting it with one another gives nourishment back. When Dr. Slaughter points out that not only the figureheads, but the practice of foreign policy would indeed change if more women took the helm of it, she speaks to the legacy of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, which is a reflection of such circularity: Clinton knew that empowering women in emergent democracies was a component not only of the broader struggle for human rights, but a direct pillar of support to our national security. Keep an open heart, without giving any ins: protect and educate the women and children, who will not then take up arms in desperation, who will not grow up hungry and optionless enough to hop on hateful extremist bandwagons.

As a development worker, I often wonder where sustainability begins as a cycle, where it takes root. I believe it takes root in people like the Survival Girls, in their very bodies, the way my body was a blueprint for the informed empathy I needed to grasp the effects of post-traumatic stress on the girls and treat them in a way that provided for those effects. Where I once saw a distinction between my bodily feeling of grief about world issues and my cerebral, head-centric assessment of facts about them, forming the Survival Girls--by every measure a successful development project--was a question of consulting my very body for answers when I met the girls: answers about where their emotional selves stood, lost in the mist of airless, windowless memories, the limbs of their loved ones strewn about an internal wasteland. It meant taking into my own heart the time I spent broken and frightened, and consulting it as a teacher. I trained myself and the girls to think once again of their bodies as safe places to be. Arnold Weinstein, a literature teacher I had in college, once threw up his hands and said, "Literature always asks the same question! It's always: 'Who is in control of the woman's body?'"

The Survival Girls are now more in control of theirs as a result of nourishing each other, and when I redefine the female role model, I think of them -- and of Charlotte and Jody, of Slaughter and Clinton, who have all worked tirelessly and thanklessly for years, in the face of criticism, to improve things the way they know how: to keep an open heart without giving any ins.

My forthcoming nonfiction book, "The Survival Girls," coming this year, features full illustrations by Jody Joldersma and its proceeds will benefit the Survival Girls.