In November, Google released the sixth edition of its Transparency Report. The report provides information on two important disclosures Google makes to governments, copyright owners, and courts. The first disclosure consists of "removal requests," which are requests from copyright owners or governments to have content removed from certain Google products. The second consists of "user data requests" from governments and courts for data on users of Google products. Given the string of privacy related issues that popped up throughout 2012, let's take a closer look at the government removal requests that were specifically labelled in the report as "Privacy and Security." The focus on removal requests rather than user data requests is because the report offers more data granularity on the former. The potential to abuse this power is huge. What if "Privacy and Security" becomes another label for web censorship to hide behind (e.g., the blocking of cartoonist Aseem Trivedi's website to prevent social unrest)?

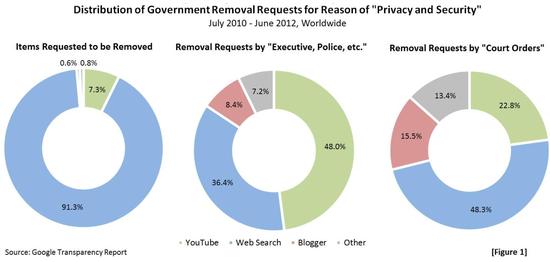

The Transparency Report categorizes each "Privacy and Security"-related government removal request ("GRR") as either "Court Orders" or "Executive, Police, etc.," and also quantifies the number of items that these requests sought to remove ("Items Requested to be Removed"). During the period between July 2010 through June 2012, of the 22 Google products that have ever been included in the report, YouTube, Web Search, and Blogger accounted for 87 percent of worldwide removal requests by "Court Orders," 93 percent of removal requests by "Executive, Police, etc.," and 99 percent of "Items Requested to be Removed" [Figure 1].

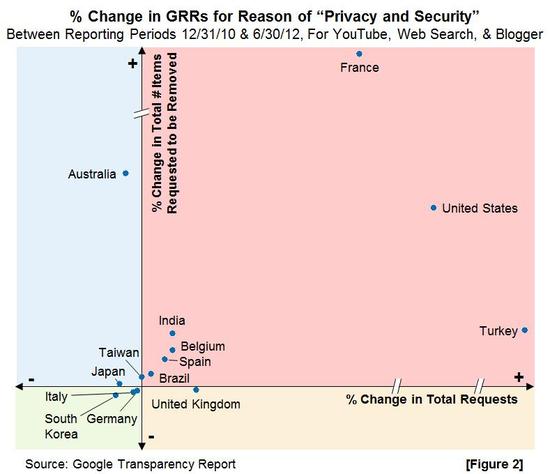

To simplify things, let's look at only "Privacy and Security" GRRs associated with these three products: YouTube, Web Search and Blogger. If the growth in number of GRRs ("Court Orders" and "Executive, Police, etc.") is plotted against the growth in number of "Items Requested to be Removed" between the six-month periods ending in December 2010 and June 2012 [Figure 2], a couple of things are striking.

First, and perhaps most surprisingly, a group of countries (Germany, Italy, South Korea, and nearly Japan) had witnessed a decline in both the total number of "Privacy and Security"-related government removal requests ("GRRs") as well as "Items Requested to be Removed." Meanwhile, the U.K. saw an increase in the number of GRRs, but the number of "Items Requested to be Removed" actually declined, while the opposite was true for Australia and Taiwan. As would be expected, most countries (Belgium, Brazil, France, India, Spain, Turkey, and the United States) fell in the upper right quadrant, exhibiting an increase in the number of GRRs with a corresponding increase in the number of "Items Requested to be Removed." Keep in mind that this represents a snapshot of two periods in time, so variations and one-time events in between that may affect the results are not explicitly captured here.

Over the past few years, particularly evident during the Arab spring, non-Web Search platforms (e.g., YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, blogs, etc.) have increasingly become a more dominant and effective vehicle for users to express themselves, promote their causes, and to share their stories. In turn, the data suggests that governments may have also evolved their tactics to match this shift. During the last half of 2010, nearly two-thirds of all "Privacy and Security"-related GRRs and 99 percent of all "Privacy and Security"-related "Items Requested to be Removed" were directed at content found on Google's Web Search product [Figure 3]. However, the first half of 2012 showed a dramatic shift. In this period, GRRs directed at Web Search made up only about one-third of all removal requests, with another third directed at YouTube. The number of "Items Requested to be Removed" also showed a similar shift, with Web Search declining to 85 percent and YouTube rising to 7 percent from 1 percent. Note: South Korea's number of "Items Requested to be Removed" directed at Web Search was extremely high in the last half of 2010, but even after removing South Korea from the analysis, the general shift in platform focus was still present.

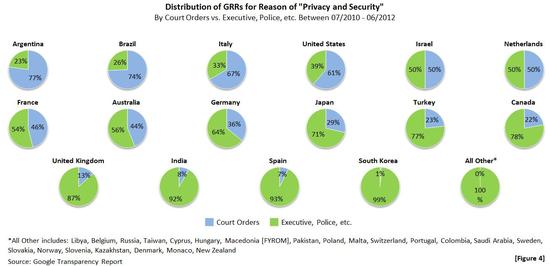

Although there has been an increase in the number of government removal requests ("GRRs"), have these requests gone through the rule of law? Specifically, were the removal requests more likely to be ordered by the court or some government agency / official? A look at the data reveals that judicial oversight over GRRs varied across countries [Figure 4] -- with only Argentina, Brazil, Italy, and the United States having a majority of their requests coming through "Court Orders" as opposed to "Executive, Police, etc."

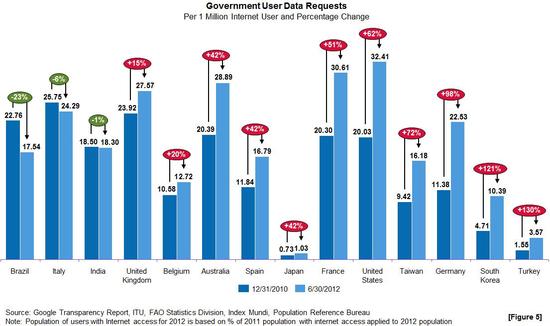

While the focus has been on government removal requests thus far, a review of governments' requests for user data of Google products is also important since user data are more likely to contain much more personal and sensitive information. The Transparency Report data suggests that the majority of governments have expanded their reach [Figure 5]. For the same set of countries analyzed above, only three showed a decline in the number of requests for user data per 1 million Internet user -- the remaining 11 countries experienced, on average, a 63 percent increase in user data requests.

As more of our lives move into the cloud, social media companies, email providers, and other technology and telecommunications firms will continue to become larger targets by governments seeking to remove certain pieces of information from the Internet or searching for information on their citizens. For example, although the majority of its removal requests come through "Court Orders" and it has experienced a decline in the number of government requests per 1 million Internet users, Brazil recently passed a money laundering law that permits police to obtain, without a court order, certain pieces of data from the Electoral Justice, Internet providers, phone companies, financial institutions, and credit card companies. Governments need to ensure that proper controls are in place to protect user data and content from illegitimate access and removal. The U.S. Congress took a first step by updating the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act to limit the government's access to users' electronic communications. The White House, likewise, created the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights to blueprint how businesses should handle users' data. But, it's just as essential that companies set up clear policies for governing if, and when, they remove data or hand over user data to governments. Google, Dropbox, LinkedIn, and Twitter have begun to shed light on government requests and how frequently they respond to those requests. One question left unanswered here is what happens when removal and user data requests originate not from governments, but from within the companies that hold the data?