Sandy Tolan knows Palestinian life. His first book, The Lemon Tree: An Arab, A Jew and the Heart of the Middle East (2006) was followed up by his popular blog, Ramallah Café: Facts on the Ground in the Middle East. Now he gives us Children of the Stone where we hear more about some of the people we've met at his café.

What we also get is an unexpected "symphony" in four movements with magical Interludes; a blend of biography and politics with a literate discussion of music. The book's subtitle: The Power of Music in a Hard Land refers to the profound influence music can have on people who live in a perpetually punishing environment.

So often films and stories from Israel and Palestine concentrate on the conflict between these two cultures, rather than life as it is experienced on the ground; daily life amid stoning, shooting and bomb explosions. We need to be reminded that underneath the wreckage are ordinary people struggling to find normalcy, a reason to be feel good about being alive. This is what we get in Children of the Stone because music is transformative. Music heals. Not just for the individuals in the story but for the reader as well.

The principal character in Tolan's story is Ramzi Hussein Aburedwan, a Palestinian boy with a powerful right arm. Once it threw stones at Israeli soldiers but his arm is eventually re-wired, not to administer violence, but to pull a bow across viola strings. Ramzi secures himself a scholarship to the Conservatoire d'Angers in France; is invited by Daniel Barenboim to perform with the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra; and eventually returns to Ramallah to establish a music school for Palestinians living under military occupation.

Muscle memory is the beginning of his transformation.

"To become a string or horn player or a pianist means to be rewired physically, " writes Tolan. "Muscle memory is the body's learned repetition of a pattern of notes, but not just for building a repertoire. It also transforms the individual."

Ramzi's transformation starts at Apple Hill summer music camp in New Hampshire. Totally out of his comfort zone, the 18 year-old wonders why people don't eat olives with their breakfast. Why they dunk small bags into water to make tea. Why there are so many instruments he's never seen before: clarinet, bassoon, oboe, French horn.

And what about reading sheet music? Back home he had assumed that his music was written in some type of Arabic notation. Certainly, the other musicians at music camp are reading music in their own languages too.

"Ramzi looked over at his neighbor's sheet music," Tolan tells us. "It was the same as his. He stole a look at another music stand; that music was identical, too. Amazingly, there was no difference. Everybody was reading in the same language. Ramzi said nothing. He kept this revelation to himself."

Apple Hill's director announces that Ramzi is to play the viola part in the Mozart Piano Quartet in G Minor, to be performed at the summer camp's final concert. When Ramzi first looks at the sheet music, he freezes.

He is terrified. Instead of half and quarter notes, with rest stops in the expected places, Ramzi saw a jumble of black notes jammed into a single measure: ascending and descending scales of eighth and sixteenth notes; quarter notes followed by a sixteenth-note rest; full note trills, followed by a sixteenth note si-do-si, played fortissimo, and suddenly piano. The very speed of the piece, combined with the volume and rhythm changes were far beyond anything Ramzi had ever attempted. It was so far beyond his level that students and teachers alike wondered if it had been wise to ask him to learn it.

But he does learn it.

Painstakingly, excruciatingly, literally one note at a time. His teachers clapped the rhythms. They placed their hands on his back and shoulders, straightening him so he could put his whole body into the playing. He needed to know the precise location of the bow on the string, what string it was on, and what finger placements he would choose for each note. For the six-note phrase that opened the piece, Ramzi needed to think of it as "AN-swer the TEL-e-phone." He learned the best fingering: fourth finger, first finger, first finger, second finger, first finger, first finger. DA-da, da-DA-dadahh! DA-da, da-DA-da-dahh!

Ramzi didn't know that this Mozart whom he was struggling to learn had received bad reviews in his time for writing too many notes or that his pieces were considered "too strongly spiced;" with "impenetrable labyrinths" or "bizarre flights of the soul;" "overloaded and overstuffed." Or that the publisher, Franz Anton Hoffmeister, who had commissioned Mozart to write three quartets, thought that the Piano Quartet in G Minor - the very one that Ramzi was learning - was just too difficult, so difficult that he cancelled the other two. He doesn't know any of this, of course. What he does know is that he wants to succeed; to demonstrate to the others that a boy from a Palestinian refugee camp can play above a beginners level.

But he couldn't do it alone. it took the others to get him there. It became a common project with the other members of the quartet: Fadi, the cellist from Jordan, Bishara, the pianist from Nazareth and Nati, the violinist from Tel Aviv.

"This represented Apple Hill's ideal," Tolan writes. "Bringing together people who would ordinarily never meet, in a place where they learned to respect and listen to one another in pursuit of a common goal - in this case, a piece of music by Mozart."

Nati, the Israeli violinist, for example, liked to play as fast as possible. He was asked to stop. "Nati, it's not all about you," the teacher said. "If you play your notes in isolation, that doesn't mean anything. You have to buy into the idea that every note and every person is of equal importance." Gradually, the 12-year-old learned that his job was not just to play his part, but also to listen to the Palestinian guy on the viola.

On an evening in early August, Mozart's Piano Quartet in G Minor was played to an audience and Tolan's vivid description of the performance is goose bump material.

Ramzi looked at Nati, whose bow hovered above the strings, ready to attack. Nati inhaled quickly, and simultaneously the three string players leaned sharply downward, pulling their downbows for the first note. Simultaneously Bishara brought his hands down on the piano keys. Six notes of the opening motif echoed in the concert barn and Bishara played the answering motif. Then the six notes again, Bishara's second interlude; and the chamber musicians were in it.

The piece was taking off and Ramzi was inside it, no longer consumed by his worries. A musical conversation was bringing the theme together ... I can do this better, the violin seemed to be calling, only to be answered by the viola and cello, and Bishara's right hand waterfalling right and left along the upper registers.

Ramzi felt the music in is body. He experienced a surge of feelings he hadn't been aware of during rehearsal: elation, sadness, a sense of profound relaxation ... joy that came with such intensity that Ramzi didn't know if he could contain it.

He had to remember to count the beats, to concentrate. A passage of sixteenth notes was approaching ... he looked over at Fadi on cello - younger but far more experienced in music - who exaggerated his gestures, trying to show Ramzi what was coming next.

They reached the fourth movement and raced toward the end. Ramzi felt like he was on a runaway train, hurtling toward the station. He leaned forward ... now aware of his teachers and fellow students, rapt and apprehensive, rooting for him, wondering if Ramzi was going to make it.

DA-da, da-da-da-da-da-da-da DAH!

Then for the briefest moment, silence, as a panting Ramzi looked over at Bishara, Fadi and Nati. They exchanged astonished glances, as if to say, What just happened? The room burst into applause. Teachers, students, parents and the visitors from rural New Hampshire sprang to their feet. Ramzi looked at Eric [the Apple Hill director], standing in the back of the room. Tears were streaming down his face."

A transformative experience. Not just for Ramzi but for the reader too. This reader found herself choking back tears, poised to jump out the chair with jubilation.

The New Hampshire experience changes Ramzi's life. He accepts a scholarship in France for a rigorous four-year education in music, and eventually returns to the West Bank to establish his music school in Old Ramallah that he names Al Kamandjati, the violinist. Tolan's account of Ramzi's journey is described with superlative story-telling skills. As a veteran radio journalist, he uses words to paint pictures, sending visual impressions straight to our hearts. He understands the use of natural sound to tell a story and in his writing, the sounds-through-words give the story a powerful presence.

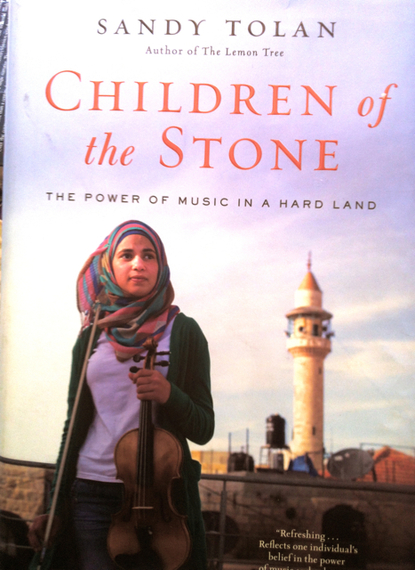

Eventually, we meet Ramzi's other music teachers, many of whom gave up lucrative and prestigious jobs to teach at Al Kamandjati. And we meet many of his students too. Look at the book cover. That's Alá Shalada, holding her violin. We can't be sure but it could be the same instrument that her older brother, Shehada made especially for her after being dispatched by Ramzi to study with master craftsmen in Italy and England. Once, at the check-point near Nablus, a soldier doubted that it was a violin in her case. Before she was allowed to pass, a humiliated Alá had been forced to open her violin case and prove that she could play the instrument.

Reading Children of the Stone gives the reader an opportunity to get acquainted with Daniel Barenboim and experience his extraordinary friendship with the late Edward Said. We learn the backstory to the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra and the role played by Yo-Yo Ma; why they picked Weimar for their first concert, including the significance of Goethe; why Barenboim chose Beethoven's Seventh as the first piece for the Weimar Workshop.

Tolan describes several episodes of musical intifada, non-violent resistance: confronting the decades-long occupation by reclaiming space through music. One was at the military checkpoint between the northern West Bank and Jerusalem.

Two dozen young musicians, all members of the Al Kamandjati youth orchestra, many dressed in black shirts and pants, began piling into the bus, carrying their violins, cellos, trombones and clarinets. Into the belly of the bus went snare drums, cymbals, timpani, backpacks and sheet music. They were about to confront the occupation in perhaps its bleakest place: the wall and military checkpoint at Qalandia.

They were told to tune on the bus. Twenty-nine year old Jason Crompton, an American pianist was the orchestra's conductor.

Now Jason stood, arms raised, before the musicians - about twenty-five children and perhaps half as many teachers. The orchestra was poised, bows and brass in position. "The sound of Mozart's Symphony No. 6 filled the terminal. They played all four movements.

Then, Bizet's Danse Bohème.

Later, a few of the players would insist that they had seen two soldiers dancing.

Afterward, Alá said it was the best concert of her life. It was only a few years since she had walked through the slanted copper door at Al Kamandjati, pointed at a violin and asked for her first lesson.

By the end of the book we know that Ramzi Hussein Aburedwan is a complicated man with a lot on his mind. He is not necessarily a patient teacher or an easy leader to work with, yet he is a man who succeeded in fulfilling his dreams.

Children of the Stone is not as big as the story in The Lemon Tree, but it is an astonishing story related with admirable talent. Tolan offers a skillful mix of reportage with heart bursting inspiration; the kind of mix that informs while awakening compassion and hope. And informs it does. To support his descriptions, there are over 100 pages of notes with an extensive bibliography.

In this way, Children of the Stone is a book to be studied as well as enjoyed. It should be savored, shared and argued about. Perfect material for a reading group. I look forward to reading it again, perhaps while listening to Mozart's Piano Quartet in G Minor... or his Symphony No. 6, or maybe ... Beethoven's Seventh.