Saving face and maintaining one's dignity is determined by cultural norms. Most of us in ethnocentric white western societies forget this and expect everybody to be guided by Anglo American/Northern European perceptions. Consequently, when Jacintha Saldanha took her own life two years ago after finding herself in the middle a radio prank, nobody could understand why.

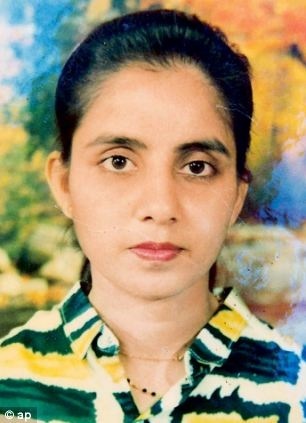

Jacintha was the 46-year-old, mother-of-two who worked at King Edward VII's Hospital Sister Agnes in London, England; a hardworking, devoted nurse; the particular nurse that just happened to answer the telephone on December 4, 2012 when two prank callers rang from a radio station in Australia, imitating Queen Elizabeth and the Prince of Wales. They wanted to ask about the health of their granddaughter-in-law, the Duchess of Cambridge.

The whole world knew that Kate was being treated for hyperemesis gravidarum or severe morning sickness. Jacintha fell for the hoax and transferred the call to the nurse looking after the Duchess who then spent two minutes speaking with the two radio DJs, Mel Greig and Michael Christian while they purposely used -- as they described it -- "ridiculous comedy accents." The theatrical hoax was taped for future broadcast. After clearing the prank with their lawyers, it went on the air.

When hospital executive, John Lofthouse learned of the prank call, he condemned it as an act of "journalistic trickery" that no nurse should have had to contend with. The hospital did not discipline the nurses after Buckingham Palace made it clear they didn't blame them for the incident. That should have been the end of the incident.

But it wasn't. Three days later on December 7, Jacintha committed suicide.

"Why did she kill herself? It's the million-dollar question," wrote Delia Lloyd in a sympathetic analysis in the Washington Post. BBC correspondent, Nicholas Witchell said that it had been suggested to him by hospital staff that Saldanha felt "lonely and confused" as a result of the incident. It is clear that anger was a driving force. She blamed the Australian radio hosts for her death and asked them to pay the mortgage on her family's home in Bristol. (The Australian radio station subsequently donated £289,000 to a family trust fund.)

"I was mentioned in Jacintha's suicide note," says Mel Greig, the DJ who had pretended to be Queen Elizabeth. "Not 'the Australian DJ' (but) my name. She thought of me before she took her own life. How can you not feel guilt and blame? And I always will, but I have learnt to deal with it now."

It's been two terrible years for the Australian DJs: death threats, stalking and harassment. Initially, both were moved to a safe house for protection. "I was in lockdown for months," Greig says. "There were bullets with our names on it sent to police stations."

Bad business. Sad business. But dark stuff that we can learn from.

Firstly, we can recognize that emotional resilience may be culturally determined. "Why did Jacintha kill herself?" Cultural anthropologists and psychologists might very well conclude that she suffered from intolerable shame.

A cross cultural study of 72 nations by the University of Zurich demonstrates that Middle Eastern and Asian cultures have an extremely low tolerance for ridicule and that -- when manifested publicly -- it results in personal humiliation. "Face," what we Westerners call dignity, is a critical mental health issue in Middle Eastern and Asian cultures. Jacintha grew up in India and lived for several years as an adult in Oman. Her emotional coping mechanisms were decidedly non-Western.

As a woman on anti-depressants, Jacintha was already emotionally fragile. When she realized that she was the primary instrument in the execution of a practical joke on a highly esteemed member of the British Royal Family, she lost face and couldn't recover.

In hindsight, we wish we could have taken Jacintha's shoulders in our hands, gently

shaken her and said: "Hey! It was just a joke! Kate doesn't think it was so terrible! Neither do we. Don't give it another thought!"

But no one could reach Jacintha with this message. In one of three suicide notes, she took full responsibility for "what happened," as if "what happened" was an irredeemable disgrace.

The second lesson from the Australian radio hoax is to recognize that pranks and practical jokes call for caution. Although they are unquestionably legal and covered comfortably under our civil right to self-expression, pranks can have negative consequences.

Says Australian DJ, Mel Greig:

"Think about how it is going to affect the other person. If you don't know them, if you don't know how they can handle it, don't do it. You... have to look out for each other."

As our western urban centers become increasingly multicultural, this is good advice from someone whose life will never again be the same as a result of a practical joke. The message: we need to pay attention to the decoders of our communications. We need to pay attention to the various participants in our scenarios. How will the "joke" be perceived?

It is legal, yes, but will it cause harm?

We ignore this at our peril whether it's off-the-cuff remarks, slogans, posters or cartoons.

To pretend that it doesn't matter is another mistake of white privilege.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this post incorrectly referred to Kate Middleton as Queen Elizabeth's daughter-in-law.