Last week I stood inside the crumbling walls of the last synagogue in northern Iraq. Abandoned over sixty years ago, the 2700 year old tomb of Nahum, rests in the Christian town of Al Qosh.

Nahum prophesized the end of the Assyrian empire. Over two millennia later, I was there to document the end of the existence of a multi-ethnic, multi-religious Iraq.

I had travelled to northern Iraq to bear witness to the atrocities perpetrated by ISIS against religious and ethnic minorities for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide.

The timing of the trip was appropriate given this period, the days of awe, where Jews are told, "let us have the courage to open our ears to the cries of our blood soaked earth, to the weeping of a world in pain, ravaged by hatred, ignorance, war and greed," and "may the shofar shatter our complacency."

An incredibly moving, humbling call to action, one that today is all too relevant.

As a sandstorm, never experienced in recent times, unfolded around us, I was determined to go to the tomb. If anything, as a symbolic act of defiance against the intolerance that ravages Iraq. To be one of the less than a dozen visitors that have been there since ISIS threatened the town one year ago.

While standing by the tomb, I could not help but say out loud, "you did not win, we exist." The 'you' are the various iterations of actors who have sought to destroy diversity, to eliminate any reminders of the 'we,' all of those who at some point have been 'others' from the Jews over the millennia to, in the case of Iraq, religious and ethnic minorities including the Yazidi's, the Shabak, Turkmen, and Christians.

While in Iraq, I spent two weeks visiting tents, caravans, makeshift shelters and homes, speaking to those who fled ISIS.

Virtually every person I spoke to fled their homes with no time to take any personal belongings. For the Yazidis, who have been deeply affected, most had family members killed or missing. I sat in caravan after caravan of men whose wives, mothers, daughters, are all missing. I sat as men wrote the names of their missing loved ones. Some of the lists spanned more than six pages front and back, hundreds of names.

One of the difficult parts of my work, though always a source of purpose, is how often I am reminded of my grandfather. His silence, my knowledge that he had lost everything, everyone, during the Holocaust, impacted me deeply.

I thought of him as I sat with Elias, who survived a massacre of hundreds of men by ISIS fighters last year. Elias wrote for me the names of over fifty family members including his wife, mother, and each of his sons--all of them missing, save for one.

I thought of my grandfather as debates raged on the TV screens in the Iraqi displaced persons camps, showing refugees in Europe facing closed doors.

My grandfather, as with each of those I spoke to in the camps, did everything he could to survive both during the war and after. For all intents and purposes, my grandfather entered Canada illegally. On false papers. Canada had until then had a 'none is too many' policy towards Jews.

As today, western governments made it virtually impossible for those who needed refuge, to receive it. In the face of this adversity, he showed the same resilience as each of the individuals that I met with - ordinary people yet given the circumstances, remarkable. Without his actions, I would not be writing you today.

Much can be said about Western governments asylum policies. But that evades the question that merits greater attention. How it is that we don't have the courage to open our ears to the suffering of others until they are on our borders? The crimes experienced by the people I met with were preventable, just as the horrors of the Holocaust were. Iraq's minorities were pawns in a bigger political struggle, their physical security a priority for no one.

We can talk today about opening our borders, about providing humanitarian relief. But these solutions ignore the indefinite future of exile these people face. That prolonged displacement threatens their communities' very existence. They are away from their land, from their religious institutions, from spaces where their languages and cultures can thrive, from their cemeteries and their past, from their families dispersed throughout camps. Many want to go abroad because they see no future in Iraq. They see few signs that their lands will liberated in the near future or feel re-assured that they will be protected if that happens. As a result, they do not believe that the diversity that shaped the social fabric of the Nineveh plains will once again be able to thrive.

As the West haphazardly responds to the refugee crisis, we are failing to address the source of the displacement, to end the conflicts in Syria and Iraq. It won't be easy. But unless that happens we have to accept that, though differences exist, we have been the bystanders to the destruction of community after community in Iraq and Syria, as the world was seventy years ago when Jewish community after Jewish community was eliminated.

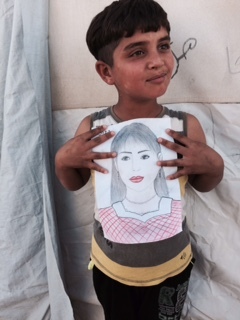

What gave me hope was the laughter of the children; their remarkable curiosity, their playfulness, their potential. It is their future that must this New Year, shatter our and the international community's complacency and compel us to act. Their future cannot be one of permanent exile. There is nowhere for them to go, save for the lucky few.

For their future, church bells must ring, Yazidi's must be allowed to pray to their god, and Shia shrines must exist in the Nineveh plains. And one day, the Synagogue in Al Qosh must be rebuilt.

We live in a remarkable world, filled with beauty and kindness. I was told of neighbors saving neighbors, of compassion shown at times even by the unlikeliest of individuals, even ISIS fighters.

Those who have so little shared with me day after day their food, their water, their homes, and their friendship. For that, this New Year, I am so grateful.