Tonight marks the beginning of the seventy-fifth annual NFL draft. As a fan of one of the worst teams in the National Football League, the Buffalo Bills, the draft provides me with a rare respite from the trials and tribulations of Buffalo's enduring mediocrity. Don't get me wrong - the Bills have whiffed on more high-round draft picks in the last ten years than almost any team.

But at least in theory, the draft is the biggest redistributive element of the NFL. In that sense, thirty-two fan bases have something to get excited about every April when the NFL convenes for its annual dog and pony show of new talent.

The draft is also a popular subject for football pundits. Before the draft, commentators partake in heated debates about the pro-readiness of college prospects. Arguments ensue concerning player stats, systems, coaches, intangibles, off-the-field issues, and fundamentalist religiosity. NFL pundits spend innumerable columns completing "mock drafts," predicting where certain players will be drafted and by whom. I'm told by friends in the League that front offices begin thinking about their draft strategy even before the end of the NFL regular season.

Given the draft's centrality in the football world, it's surprising that professionals of all stripes are notoriously crappy at evaluating the long-term potential of college football talent. General managers, college scouts, charlatans professional writers such as Bill Simmons, owners, and even other players routinely mis-evaluate "busts," or professionally incapable football players.

Anecdotal evidence abounds: Tom Brady, arguably the best quarterback of the 2000s, was selected 199th overall by the New England Patriots. Ryan Leaf, one of the biggest draft busts of all time, was selected second overall by the San Diego Chargers.

But could this just be unsubstantiated conjecture? Surely players selected in the third round of the NFL draft were far better than players drafted in later rounds. Well, after doing some research, it turns out that GMs are even worse than I thought.

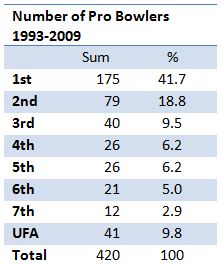

Looking at data from 1993 to 2009, I found that the NFL has had four hundred and twenty discrete Pro Bowlers, which is the NFL equivalent to an "all star." I then compiled the draft position of each player by round. From here, I had a complete dataset of draft year and number of Pro Bowlers selected in each round. After some addition, I found the following percentages of Pro Bowlers by round from 1993 to 2009. Here are my results:

Pro Bowlers have a 42% and 19% chance of being taken in the first and second round, respectively. After that, the expected value drops off dramatically. Perhaps my most striking finding is that statistically, a Pro Bowler is just as likely to have been taken off of waivers as an undrafted free agent as they are to have been selected in the third round of the NFL draft.

Granted, a player earning Pro Bowl status ignores the possibility that a draft selection might turn into a solid starter, albeit without star potential. Moreover, this study takes for granted the flawed Pro Bowl selection system as well. Despite these caveats, however, all other things being equal, teams would rather have a Pro Bowler than not. Last year's Super Bowl contenders, the New Orleans Saints and the Indianapolis Colts, each boasted seven Pro Bowlers on their rosters. The best units of the 2009 Super Bowl squads, the Pittsburgh Steelers' defense and the Arizona Cardinals' offense also had three Pro Bowlers each.

At a minimum, this analysis shows that forecasting player talent is a fool's errand, and that the NFL draft is a crapshoot. Despite the revisionist historians' accounts, New England's discovery of Tom Brady was due to randomness. How else can you explain thirty-two teams passing on him an average of six times prior to his ultimate selection with the Patriots?

Instead of embracing this randomness and identifying it as such, pundits continue to make hyper-specific prognostications about the pro potential of any given selection. These commentators are doing fans a disservice by purporting to be able to predict something that we cannot forecast.

As both a staunch fan of the National Football League and a budding social scientist, it pains me to see such epistemic hubris. To paraphrase an old adage, wisdom is being able to say "I don't know." The expertise fetishism fans project onto general managers is no different than the idealistic faith investors place in all star asset managers. With football, as in life, humanity was never hurt by a realistic appraisal of its limitations. Maybe after some more draft debacles, we will finally come to terms with what the numbers plainly tell us. But until then, try not to be too smug when listening to your fellow football fans rave about their team's "can't miss" early round picks. Delusion is a powerful force.