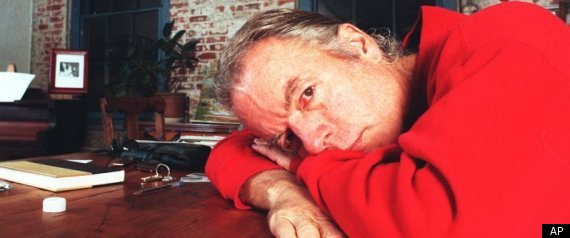

The image I hold in my mind of Spalding Gray as a performer is probably not unlike yours (that is, if you are of a certain age and were a fan) a man with a narrow, patrician face, wearing a plaid flannel shirt, sitting at a wooden desk with a notebook and a glass of water in front of him. He seemed to tell us everything about his life. He spoke, in his distinct New England accent, of his repressed WASP upbringing, the terror he felt about his mother's suicide, the tangle of his romantic relationships and his seemingly endless fascination with himself.

I first met Kathleen Russo, Spalding Gray's widow -- whom he also discussed with his audiences -- in 2006, when I was writing an article for the New York Times about Leftover Stories to Tell, a play culled from Gray's monologues that she had created with Lucy Sexton. A year later, Russo asked if I'd be interested in doing a biography of her late husband. I remembered that she'd mentioned in our interview that Gray kept journals for many years -- nearly forty, as it turned out -- and I asked her if I could read them.

Within weeks, I was reading page after page of Gray's private writings. It was an oddly mesmerizing experience from the start. The performer clearly practiced his journal writing as a serious discipline. He wrote often; for some years, he checked in every day. When he did go through a rare spell of ignoring his journals, he would come back to them regretful, seemingly ashamed that he had let it -- time, experience, insight, whatever he was trying to hold still in these notebooks -- slip away for a while.

He also wrote everywhere, it seems, when his trademark marble composition notebook wasn't handy. As I sifted through his archives, I came across snippets of thoughts and notes he'd written to himself, in tilting boyish cursive, scrawled across hotel stationary, an Amtrak napkin, a Breast Cancer Coalition pamphlet. (At one point, when Russo was emptying out a box of his papers and handing them over to me, a Tampax insert fell into my lap. It was, I thought, a fitting tribute to Gray's career of ushering intimate details into public view.)

These notes, like so many of the passages throughout his journals, were arresting for their searing poetic honesty. In a way, these missives were more startling because they were compressed, one or two lines that seemingly captured a whole world of emotion -- acute, uneasy, fascinating emotion. "To stare down into the deep sleep of children," he wrote, perhaps after he'd had his two sons with Russo, on one piece of scrap paper. "The new fear was that mom had not only killed herself," he wrote on another, "but had also laid the groundwork to kill me."

The longer entries in Gray's journals reveal a man struggling deeply, though not without humor, with almost every aspect of his life. He cannot settle down without looking over his shoulder for another possibility, another life. He drinks too much. He has affairs with men and women -- but mostly women, mostly strong-minded, willful women who help steer his life when he can't manage on his own. He yearns for stability even as he shuns it. Most of all, he is torn between his compulsive desire to reveal himself and his fear that he may be foolishly trading his life for recognition. "I felt a slight feeling of loss and bitterness that these people were using me as their jester," he wrote in 1979.

He has the "realization that I'm incanting the same neurotic fears each night," in the mid-'80s. He worries he's become a "crazy, neurotic wind up doll" in 1991. And yet, throughout, he quietly understands that this particular theatrical form -- the confessional monologue -- is so wholly suited to him, providing him with an otherwise elusive sense of emotional calm and purpose, that he could never give it up. Nor could he give up the approval of his audience, under whose watch he'd come to believe in his own existence.

For a period of about five years toward the end of his life, Gray was gratefully, albeit tentatively, happy. He'd married Kathleen Russo, helped to raise her daughter from a previous relationship and had two sons of his own with her; they'd made a comfortable home together in Sag Harbor, NY. And yet still Gray found things to be anxious about -- simply being happy made him a little nervous but he also wondered what would become of his work-life now that his life-life was relatively content.

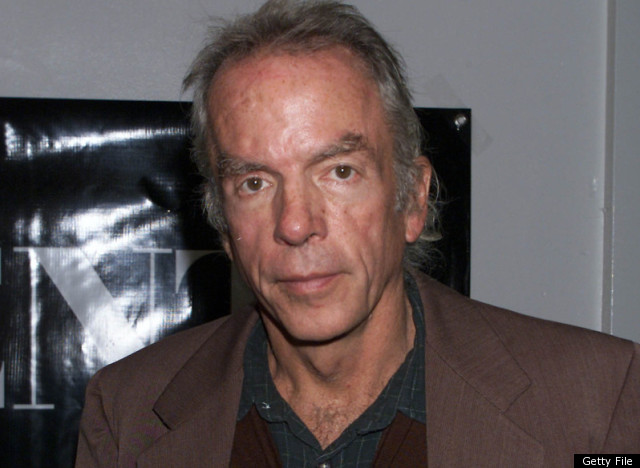

In 2001, the answer to this existential question came in the form of a brutal reality. Gray and Russo, as well as three other of their friends, were in a serious car accident while vacationing in Ireland. This left him with an orbital fracture, a broken hip and a permanent limp, among other injuries. As he continued to struggle physically, he faltered emotionally. He began to recount his experience before audiences -- of the accident, of his emotional and physical trauma -- in an effort to find his way back through a monologue.

And yet, as Gray makes clear in his private writings, he could not stop himself from telling another story that had been set in motion by the accident: that the dark shadow he'd felt looming was now overtaking him, that his fate was, as he had long suspected, inextricably linked to that of his mother. "All my life I have been afraid and all my fears culminated in this accident," he wrote while in the hospital in Ireland. "I can say, 'There, you see something bad did happen in this random world.'"

Being in the presence of Gray -- as one strongly feels in reading these journals -- can be a demanding experience, but it is also a deeply moving one. Where Gray charmed his audiences with the "banal truth" of his life, as he once claimed his monologues to be, these journals allow for the full range of his humanity by presenting the raw material from which he ceaselessly shaped his myth.