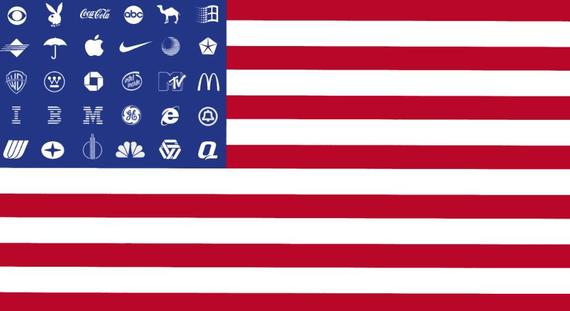

The Supreme Court's Citizen United decision, giving corporations the right to unlimited political contributions usually kept secret from voters and shareholders, was just the most recent in a series of rulings giving corporations "personhood" rights. In her new book, Corporate Citizen?: An Argument for the Separation of Corporation and State, Stetson law professor Ciara Torres-Spelliscy documents corporate efforts to dramatically enlarge their political and commercial speech and religious "rights" through lawsuits, campaign contributions, and lobbying. They also use these "rights" to limit their liability for the damage they do to investors, employees, customers, and the community. In an interview, Torres-Spelliscy discussed the impact corporate money has on preventing progress on issues like climate change and what options there are for reducing the distortion effect of corporate money from government.

The Supreme Court's Citizen United decision, giving corporations the right to unlimited political contributions usually kept secret from voters and shareholders, was just the most recent in a series of rulings giving corporations "personhood" rights. In her new book, Corporate Citizen?: An Argument for the Separation of Corporation and State, Stetson law professor Ciara Torres-Spelliscy documents corporate efforts to dramatically enlarge their political and commercial speech and religious "rights" through lawsuits, campaign contributions, and lobbying. They also use these "rights" to limit their liability for the damage they do to investors, employees, customers, and the community. In an interview, Torres-Spelliscy discussed the impact corporate money has on preventing progress on issues like climate change and what options there are for reducing the distortion effect of corporate money from government.

How did you first get interested in this issue?

I first ran into the issue of money in politics as a senior at Harvard in a class called "Democracy" which was taught at the Harvard Law School. I had to read Who Will Tell The People by William Greider and that introduced me to the issue of corporate lobbying and campaign finance.

Can you give some examples of corporate money distorting the legislative process in (1) Obamacare, (2) climate change, and/or (2) post-Enron era/post-financial meltdown reforms?

As I discuss in Corporate Citizen?, corporate money can distort the legislative process by curtailing what is on the agenda of Members of Congress and by narrowing what lawmakers think is even possible. So for example, when the U.S. was revising its health care system, instead of going with a public option where the government provides health care for all, which is basically the approach of most western democracies, instead what American got with Obamacare was essentially a mandate for people of a certain income level to purchase private health insurance from private companies. This served the interests of private companies, but not necessarily the public. But because of years of lobbying--including derailing the efforts of President Bill Clinton to reform health care in the 1990s--the public option wasn't really even seriously considered as a starting point for the Obama Administration.

One of the most troubling conclusions I came to when writing Corporate Citizen? was that the American Congress seems utterly incapable of dealing with climate change. This is a potentially deadly mistake that even the U.S. military recognizes as an existential threat. When I asked environmentalists why Congressional inaction on climate was the case, I got very similar answers from scientist Gretchen Goldman, environmental lawyer Deborah Goldberg and the former head of Greenpeace, Phil Radford. They all described how industries--especially the oil and gas industries--were particularly effective at lobbying to get Congress and regulators to do as little as possible to protect the environment. A common theme each mentioned was the attempt by businesses to manufacture doubt about the underlying climate science by paying scientists to spout the industry position that climate change is not caused by man, even though the scientific consensus is that climate change is caused by human activity. This is very similar to recent revelations that the sugar industry paid scientists to cast doubt on the link between sugar and heart disease. The impact is similar, the public is confused about what the truth is, and meanwhile elected officials are provided cover for failing to act. I find this lack of urgency on the issue of climate change personally troubling as I live in Florida, close to the coast. If nothing is done about climate change federally, my community and my home could be literally under water.

Even after corporate interests like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Business Roundtable and the National Association of Manufacturers lose a legislative fight like with the passage of Dodd-Frank, they don't give up waging the war. After Dodd-Frank became law, these trade associations were active challenging many regulations that were promulgated under Dodd-Frank through litigation. For example, these trade associations were successful in stopping Dodd-Frank's proxy access rule, the conflict mineral rule and a rule on reporting payments to foreign governments by extractive industries. Frequently, the arguments raised in these cases tried to expand corporate First Amendment rights by making elaborate claims about how a given regulation was unconstitutional.

After the Citizens United decision, what are the options at the state or federal level to limit the amount or increase transparency in corporate political contributions and lobbying expenses?

As I explicate in Corporate Citizen?, because Citizens United was decided on Constitutional First Amendment grounds, it severely curtails the options for state and federal regulators to limit corporate money in politics--especially if the money is spent independently of candidates. But there is some room for Congress and the states to maneuver. For one, because of a case called Beaumont from 2003, states can still ban corporate contributions that are given directly to candidates' political campaigns. And the federal government and states can vastly improve their disclosure of the sources of money in politics--ending the dark money problem. The Supreme Court in Citizens United ruled in favor of disclosure by a margin of 8 to 1. This frees federal agencies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to all improve transparency of political spending.

Do other countries limit corporate political contributions?

According to Transparency International, Belgium, Estonia, France, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Portugal all ban corporate political contributions, as does the United States at the federal level under the Tillman Act of 1907. The catch is in over half of the 50 states in America, corporations can give money directly to state candidates. And furthermore, as I noted in Corporate Citizen? because of Citizens United, corporations are free to spend an unlimited amount of money on political ads (making the underlying federal contribution ban nearly meaningless).

So-called "dark money" is money that is spent in politics--typically to buy political ads--without revealing to the public who paid for the political expenditure. Dark money can be revealed through bankruptcies if the debtor was a source of dark money. Clever investigative reporters have discovered that when they pull the matrix of creditors in certain bankruptcies like that of Corinthian Colleges and coal company Alpha Natural Resources, they find dark money conduits are listed. This means that these corporations were spending dark money before they went bankrupt. Also on occasion, courts will order a dark money spender who is violating a disclosure law to actually tell the public where their money came from. This happened in Montana with a group called Western Tradition Partnership (which later changed its name to American Tradition Partnership). As I explain in Corporate Citizen? this group had bragged to donors that only they would know who had influenced the election. This promise of anonymity was one Western Tradition Partnership couldn't legally keep.

What is the best hope for solving this problem?

The antidote to expanding corporate political power is placing more power in the hands of American voters. While certain regressive states have made it harder for voters to exercise the franchise though restrictive voter ID laws or cutbacks in early voting, there is some forward motion to empower voters as well. As I wrote in Corporate Citizen?, California and Oregon have adopted automatic voter registration. And since the book was written, Connecticut, Vermont, and West Virginia have passed similar laws empowering American voters. More states should follow suit-- placing voters back at the center of the democratic process.